Many of these companies include clauses in warranties, typically covering four years, requiring customers to buy spare parts from the manufacturers whenever there is a need to repair a vehicle. Moreover, after the warranty period expires, the car makers supply spare parts and other diagnostic tools only to authorised dealers and not to independent repairers, thereby limiting consumer choice, the commission noted.

The commission not only ordered the companies to desist from such activities, but also imposed a one-time fine of Rs 2,545 crore on 14 manufacturers, ranging from Maruti and Tata to Honda and BMW. The fine may not be huge as it amounts to just 2% of the companies' total revenue over three years, but it is not insignificant.

“Original Equipment Manufacturers like Skoda, Mahindra, Nissan and Fiat, which completely restrict access to spare parts and diagnostic tools, coupled with an absolute cancellation of warranty if cars are repaired by independent repairers, completely foreclose the market for independent repairers, create barriers to entry and deprive consumers of any choice in the after-market for spare parts and repairs,” the commission said in its order.

Captive consumers

The regulator’s 221-page order carefully delves into the way these manufacturers have managed to earn huge profits from the spare parts markets all these years and what excuses they were deploying to get captive consumers.

Car companies said on Wednesday that they would appeal against this order. "Aggrieved by this order, [we] propose to appeal against it before the appropriate forum," said a statement from Mahindra & Mahindra. "The company furnished all information and clarifications requested by the authorities in the context of the investigation."

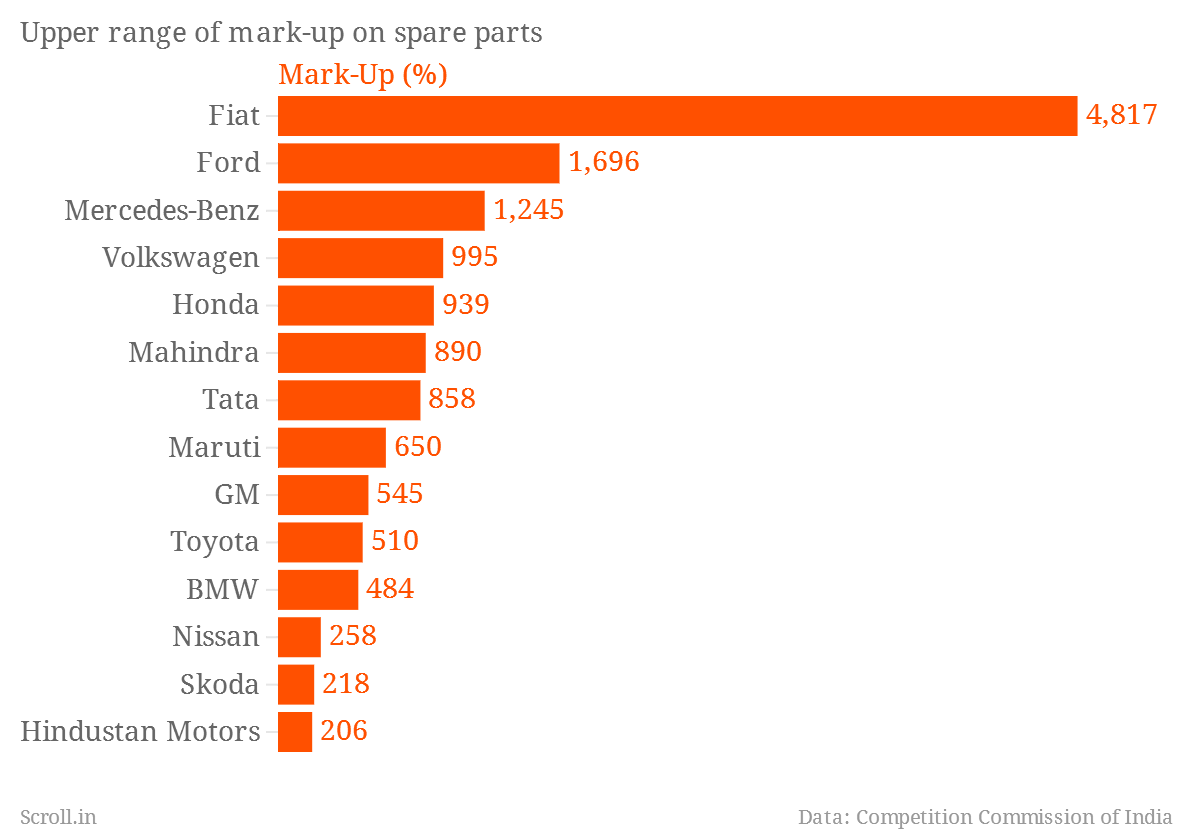

If you own a Fiat, the down payment is only the beginning. The commission's investigation found that original spare parts being sold by Fiat in India are being marked up by as much as 4,817%.

Other manufacturers also are hardly shy about inflating their spare part prices, usually by more than 100% and in some cases up to a mind-boggling 5,000%. Indian car firms, such as Mahindra & Mahindra and Tata, are also marking up their spare parts by up to 900%.

“It is evident that the OEMs not only have the incentive but have in practice raised prices of spare parts in the locked-in automobile aftermarket,” the commission concluded. “Therefore, it is no longer a theoretical possibility whether consumers may be subjected to exploitative price abuse in the aftermarkets.”

Monopoly profits

Why are car manufacturers doing this? For one, simply because they can. The firms argued, among other things, that spare parts counted as their intellectual property, that the use of third-party parts would be a safety issue and that cars come as a whole package. None of these contentions was accepted by the regulator.

Instead, the commission looked into what exactly the companies were earning by monopolising their aftermarkets and marking up prices.

Take Skoda, the Czech car firm. According to the regulator’s investigation, Skoda tends to lose money making cars for Indians. In 2010-'11, its margin in the automotive business was -0.35%. The same year, however, its spare parts unit managed a profit of 19.49%. Volkswagen was earning a nearly 50% profit from the aftermarket, compared with a paltry 0.4% profit margin on its cars. Even an Indian company like Maruti, which managed a margin of about 4.7% on automotive business in 2010, got 21% margins on spare parts.

The absolute values in these cases are obviously quite different, since cars tend to cost much more, but these numbers prompted the regulator to conclude that such high margins on spare parts could be an indication of exploiting dominant positions in the market.

The razor's edge

Cars are not like razor blades and the Indian customer is rather unsophisticated. These were the conclusions that the antitrust regulator had to make in order to ban the car firms from mandating aftermarket monopolies.

The companies had argued that customers make decisions for the lifetime of the car, so they factor in potential aftermarket prices when they buy the vehicle itself. If that were the case, then it wouldn’t be exploitative to insist that spare parts have to come from the original manufacturers.

The commission, however, pointed out that this was an argument better suited to Gillette. The razor company uses a design that doesn’t allow blades from any other firm to be used on their products, which could potentially be analogous to car companies insisting on their own spare parts.

But the regulator concluded that with blades it was easy enough to switch the primary product, in this case, the razor, if customers felt they were being cheated on the spare parts. With cars lasting for an average of 13 years and costing vastly more than razors, the same did not apply.

A close shave

“Where it may be easier for a consumer to shift to a different razor (where an average Gillette razor may be priced at Rs 500) than for the same consumer to shift to a separate car (the average price of a car would be Rs 3 lakh or more), the consumer will shift to another primary product than pay incrementally exploitative prices for the secondary product(s),” the commission concluded.

The regulator also said that it couldn’t presume customers were sophisticated enough to do a “life-cost” analysis, keeping in mind the overall costs that a car would include, such as spare parts – especially because even the car makers do not often have all the information about price and availability at the point of sale.

“If the OEMs are themselves not in possession of the basic data, to expect that an average prospective owner of a car will be able to overcome the hurdle of the high cost of information gathering and thereafter successfully engage in analysing such data, given the various future variables to successfully undertake a whole life cost analysis would be unreasonable," the regulator said.