After the 1857 mutiny, the British destroyed two-thirds of the Red Fort and turned it into military barracks. When the Delhi Durbar took place in 1911, announcing the shifting of the capital, they restored the fort a bit, including its museum. When the British left, Nehru hoisted the Indian flag at the Red Fort on 15 August 1947, as did Narendra Modi this year. Despite the awe-inspiring new capital the British had built, the Red Fort in the old city remained the symbol of authority. Even today, you could hear the fringe right in Pakistan talking about hoisting the Pakistani flag not on the Rashtrapati Bhavan but on the Red Fort.

The name New Delhi at once distances from itself the old Delhis and yet acknowledges being part of a succession of empires. Post-colonial India happily inherited this colonial city built deliberately for cars rather than pedestrians, for the rulers rather than the ruled. (Commoners took over India Gate anyway.)

Inheriting the Raj

If you stand at the majestic Central Vista, looking at Rashtrapati Bhavan, the Indian name of the Viceroy’s Palace, the largest presidential home in the world, South Block is on your left and North Block on your right. You will likely miss a detail on their gates. There is a quote inscribed in English in North Block and in Persian translation in South Block, which houses the prime minister’s office. The quote reads: “Liberty will not descend to a people. A people must raise themselves to liberty. It is a blessing that must be earned before it can be enjoyed.”

The British had to leave India in another 17 years, so those words of an eccentric English writer became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Yet, since 1947, the government of free India rules from these buildings, which officials enter every day, with those words on the gate.

It is only apt that the free Indian government is yet to change the names of a few roads in New Delhi that remind us of the British Raj, such as Chelmsford Road, Minto Road and Hailey Road.

Free India inherited the colonial state, its buildings, its laws, its system of administration. It could not pretend that the British Raj did not exist, or that it did not bring order to the chaos of the land, and created a nation-state while leaving. What is called freedom was better called the Transfer of Power.

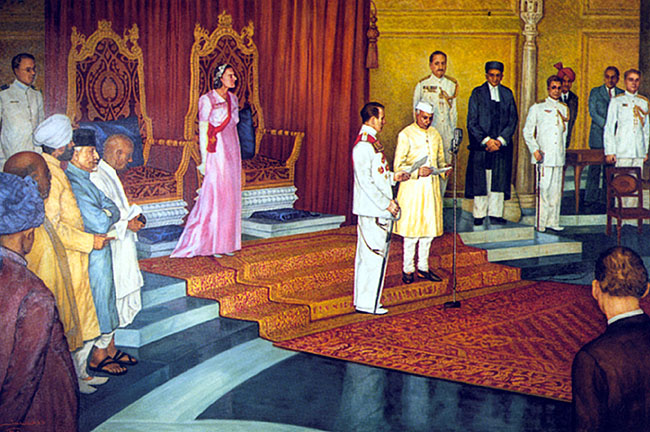

In 2001, the Parliament Annexe building’s auditorium got a new painting by VS Kulkarni. It is called “Transfer of Power” and depicts the event.

Emperor Modi

Nehru built the new India. He was the democratic emperor who ruled Delhi. His seat is today occupied by Narendra Modi, who isn’t very fond of Nehru. After becoming prime minister, he did not even go to Nehru's samadhi to pay respects, as is the custom, instead settling the matter with a mere Tweet.

In Gujarat in October 2013, as prime minister Manmohan Singh sat on stage, Modi said from the podium, “Every Indian wishes that Patel should have become the first PM of India. If it had been so, then the face and the fate of the country would have been something else Patel was a visionary.” Modi has also commissioned a 597-foot statue of Sardar Patel, which could be the tallest statue in the world and will cost more nearly five times as much as India’s Mars mission.

The Narendra Modi who wanted to give Sardar Patel his due has suddenly become a fan of Jawaharlal Nehru. "When we celebrate the 125th birth anniversary of Pandit Nehru on November 14, all schools should give lessons on cleanliness to the children,” Modi said at a Haryana election rally, adding, "Those who have regard for Nehru would join the cleanliness drive for five days along with the schoolchildren. The campaign is for children that Chacha Nehru loved. They should be taught cleanliness and healthy living.”

In invoking Nehru he isn’t simply accepting his new friend Shashi Tharoor’s polite suggestion. A landmark event like Nehru’s 125th birthday can’t be ignored, especially because it is popularly celebrated as children’s day. So why not appropriate it? Modi turned Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’s Teacher’s Day into a Modi School Master day, so why let go of Children’s Day?

Since Indira Gandhi was born on November 19, Modi wants schools to spend nearly the whole week from November 14 to November 19 in cleaning up India.

Shortly thereafter, he also invoked Indira Gandhi’s bete noire Jai Prakash Narayan, dedicating to him a new scheme whereby he wants every member of parliament to adopt a village and turn it into a model village.

Narayan was a socialist and did not share the Hindutva ideology, even if he made alliance with them against Indira Gandhi after the Emergency in 1977.

The appropriation of Nehru and Indira are new and very unexpected. So far, it seemed that Narendra Modi was avoiding Nehru, and trying to be India’s second Nehru, a man who will leave his imprint for generations to come. This seemed to be the case when he announced, from the Mughal era Red Fort on August 15, that he planned to do away with a key Nehruvian institution, the Planning Commission.

The appropriation of the patriarch of the opposition Congress party’s ruling family is no more bizarre than Modi’s appropriation of Gandhi.

He goes around gifting The Gita According to Mahatma Gandhi, and used Gandhi’s name to push his campaign to clean up India’s streets. Gandhi belongs to everyone. As Ashish Nandy said recently, Gandhi can be customised. Yet, one thought Gandhi made the Hindu right uncomfortable. They never forgave him for being a champion of Hindu-Muslim unity.

Narendra Modi’s fans and critics alike are still in awe of what he did this May. He won a general election with complete majority for his party, ending a 30 year old coalition era. The last time India had a majority government was in 1984, when more than half of India’s population was not even born.

It is thus curious why a prime minister with such a massive mandate needs to invoke past leaders. Modi does not need legitimacy anymore. On May 16, he silenced all critics.

The answer lies in Modi’s ambition. he isn’t here to be just another prime minister. He wants to be Nehru II. He wants to leave behind an imprint on this land as great as the one left by Nehru.

That is why he needs to appropriate Nehru, Gandhi, Indira and JP in just the same way as the British Raj needed Prithviraj, Ashoka, Ferozshah Tughlaq, Akbar and Aurangzeb. A Modified Bharatvarsha can’t be created atop Nehruvian India by ignoring the icons of independent India. It can only be created by appropriating Nehruvian India.

A Gujarati outsider may have captured the Delhi throne, but the historic capital has its own ways of reminding everyone that empires have come and gone through these neighbourhoods.