This is particularly important when marking Black History Month, which is just coming to a close in the UK and will be observed in the US and Canada in February.

The month always brings with it a debate about whether there should even be such a thing. For some there is resentment that an event should focus on the history of a particular group, as opposed to the rest of the national community. But for many, there is a special need to recognise particular heritages and achievements that have seldom informed mainstream narratives.

In America, black history month celebrates black North Americans and their traditions, while in the UK, the event was conceived in 1987 to include consideration of African, Caribbean, Asian peoples, each of whom played significant roles in the history of Britain and its historic empire. It was thought that Great Britain could only become one populace by adding these others to its conception of national belonging.

But both critics and defenders should agree that black history is not particular to black people, it is fundamental to the history of the world we all inhabit. While we commonly think of this time as an opportunity to celebrate achievements, black history is also the history of achievement’s cost and the destruction wrought upon the many by the creation of wealth for a few.

Black history is a cautionary tale about greed and ambition, an occasion for mourning no less than for celebration. After all, the root source of blackness and many of its cultural associations is slavery. And slavery helped to build the modern capitalist world.

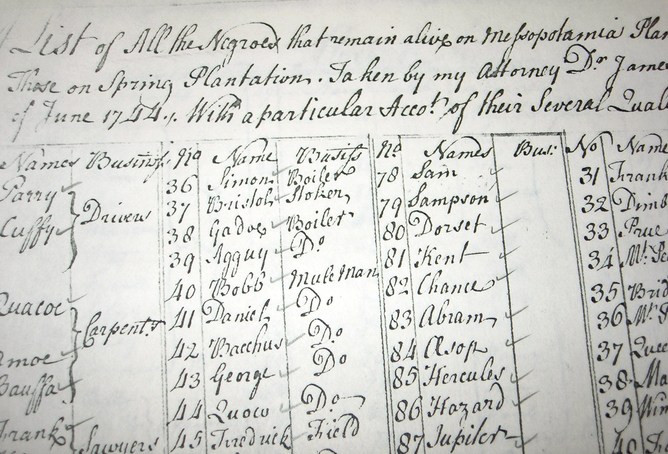

Mesopotamia slave inventory 1744. Richard Dunn

Where we are today

Building on the work of the great West Indian historian Eric Williams, several new books on slavery by Edward E Baptist, Sven Beckert, Nicholas Draper, Greg Grandin, Catherine Hall, Walter Johnson, and others, have enhanced our understanding of the absolute importance of the institution of slavery to the growth of empires, nations, and global capitalism. At the risk of sacrificing the nuance and complexity of these sophisticated texts, they can be glossed this way: No slavery, no sugar, tobacco, rice, or cotton; no sugar, no British empire; no tobacco and rice, no United States; no cotton, no industrial revolution.

The English merchant and writer Daniel Defoe put it much the same way back in 1713:

The case is as plain as cause and consequence: Mark the climax. No African trade, no negroes; no negroes no sugars, gingers, indicoes etc; no sugars etc no islands, no islands no continent; no continent no trade.

We have also gained a better sense of how catastrophic the making of empire, nation, and capitalism were for the enslaved, those who laboured and suffered to make it all possible. After all, one of the most pronounced features of capitalist development is the simultaneous production of wealth and poverty. Black history, then, is the black book of capitalism.

Two plantations

One new volume shows, in painstaking detail, the costs of slavery for some 2,000 black people in 18th- and 19th-century America. For four decades, Richard Dunn mined the inventory lists of Mesopotamia estate in Jamaica and Mount Airy plantation in Virginia. In doing so he pieced together a portrait of slave life on the two plantations. In crumbling account books and on fragile scraps of paper, Dunn found the names of these hundreds of men, women and children listed alongside the mules and cattle and pigs.

These were bare traces of the slaves’ existence, handed down by their captors in the form of proprietary accounting. By interpreting such records against the grain and alongside other sources, Dunn created family diagrams and biographical sketches that highlight struggles for identity, connection, and belonging. Some of these can be viewed online.

Mount Airy. Richard Dunn

The details of these two plantations summarise the enormity of the tragedy wrought by slavery upon the lives of individuals and families. It shows that the people at Mesopotamia and Mount Airy suffered immensely but in different ways. Despite their attempts to maintain domestic integrity these were families in crisis, beset by rampant sickness, overwork, high mortality, and disruption.

At Mesopotamia, where the death rate was far higher than the birth rate, the planters imported enormous amounts of new slaves from Africa to replace the dead workers. In Virginia, the natural increase in the population allowed slave owners to move slaves as “surplus capital” to new plantations in the expanding zones of cotton cultivation in the Deep South. In both places, people mourned the dead and the dislocated as they lamented the break-up of their families.

So in whatever month we celebrate diversity, achievement, and heritage, we might also take time to ponder these enslaved families in Jamaica and the United States, for we have inherited their losses. The deficit shows up most dramatically in contemporary inequalities between blacks and whites on both sides of the Atlantic.

For a long time, it has been fashionable to blame inequality on the cultural behaviour of the unfortunate. Jamaican slaveholders even claimed that death rates were so high because slaves stayed up late drinking and dancing at each other’s funerals. In other words, they were killing themselves by mourning.

Perhaps it is time to think differently about heritage, less about cultures than about the circumstances resulting from privileges and disadvantages that accumulate over time. If, as the new histories of slavery show, we can connect our present to the legacies of slave-holding and the damage done to the enslaved, perhaps we can also articulate a means of reparation.