Higher education institutions in Afghanistan are average, notes Yousafzai while explaining his move. And the university in Delhi gave him the opportunity to study his favourite subject: political science.

Like Yousafzai, many young Afghans are flocking to the universities in Delhi. It helps that there are several pockets of Afghan refugees and mushrooming Afghan food outlets.

“I am having the time of my life here even though I am far from home and family,” said Yousafzai. “Friends, studies and games like cricket and football keep me busy.” Unlike in Afghanistan, he can stroll from Lajpat Nagar to South Extension at midnight without worrying about lurking violence.

Distrust and suspicion

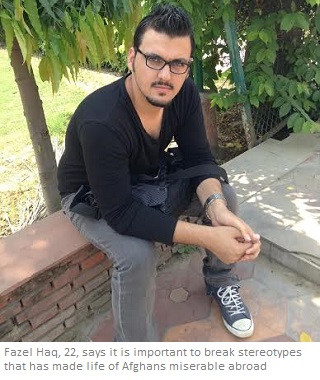

But not everything is ideal. Hunting for an affordable paying guest accommodation can be daunting in Delhi. Like students from Kashmir and North East India, Afghan students face problems while house-hunting. “It is difficult initially because landlords do not trust you easily, so most of us have to opt for university accommodations, whether we like it or not,” said Fazel Haq, a Master’s student at Jamia Millia Islamia University.

Haq, 23, recalls an incident from last year when he went on a trip to Shimla with his friends and struggled to rent a hotel room. “They looked at us with suspicion,” says Haq. “When they got to know we are Afghans, they asked us to leave the hotel premises.”

Haq stays at the International Boy’s Hostel of Jamia Millia, which is offered to outstation students. A student of public administration, he wants to join the foreign service in Afghanistan.

“It is important to break the stereotypes that have made our life miserable in many parts of the world,” said Haq. “Just because some people in Afghanistan have deviated from the right path does not mean everyone has to pay for their dastardly actions.”

The stereotypes exist even in India. Many people in India bracket Afghans and Taliban together. “They [Taliban] are monsters, and every sane person in Afghanistan loathes them,” said Yousafzai. His understanding of the Taliban is based on the same sources as people in India or other countries. “I do not have any deep knowledge about them to tell you how they function,” said Yousafzai. “I come from a city in Afghanistan where Taliban has little presence and nobody really likes them.”

Afghan students are often asked questions in India about Taliban and Al Qaida. “People must understand that we are the victims of terrorism, not the perpetrators,” said Haq. He adds that some Indians take Afghanistan as a nation of warmongers. “I have often been asked if I know Osama, can I operate an AK-47, have I been to Tora Bora.”

Yousafzai wants to break all these stereotypes and present the real picture of Afghans before the world. He wants to explore the world’s best universities but eventually return to Afghanistan.

Fomenting trouble

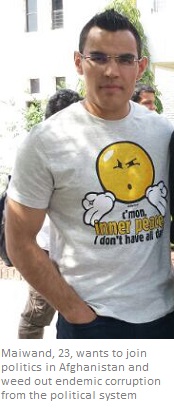

Endemic corruption is one of the biggest challenges in Afghanistan, says Maiwand (23), a student of public administration at Jamia Millia Islamia University. He wants to join politics in Afghanistan and weed out corruption from the political system.

Both Maiwand and Haq are not too fond of Pakistan. “It is no secret that Pakistan is fomenting trouble in Afghanistan through Taliban, but the international community remains a mute spectator,” said Haq. “They force so-called jihad on Afghans.”

For many of these students, the gap in educational standards in India and Afghanistan is a challenge. The late admission of children in Afghanistan makes matters worse. In India, a child is enrolled in school at the age of three or four, while in Afghanistan children are sent to school at seven or eight years. “We cannot expect an illiterate father to send his son or daughter to school at an early age,” says Yousafzai. “The problems of insecurity, poor infrastructure, lack of qualified teachers and poverty affect children enormously. But I am hopeful things will change.”

This is an edited version of a post that originally appeared in Afghan Zariza.