Two months later, Pandey still awaits a letter of regular employment. The bank account has not been opened. And he has begun to suspect that it wasn’t generosity that prompted the factory owner to admit him to a private hospital.

“He did not want me to go to the ESI hospital,” he said. “He was worried that the ESI officers would get to know that he had not enrolled me in the scheme.”

Better known as ESI, the Employees’ State Insurance scheme gives cover for sickness, disability and death to workers who earn less than Rs 15,000 a month. For this, the employer must enroll the worker with the ESI Corporation. The worker contributes 1.75% of her salary and the employer puts in another 4.75%. But many employers, keen to cut costs, do not enroll their workers with the ESI. Not only does this deny workers like Pandey access to insurance benefits, it also keeps the government in the dark over the true scale of shop floor injuries.

A hidden crisis

In 2005, the International Labour Organisation published a report on work-related accidents around the world. It pointed out a strange anomaly: India had reported 222 fatal accidents that year, while the Czech Republic, with a working population of about 1% of India's, had reported 231. The ILO estimated that the “true number of fatal accidents” taking place in India every year was 40,000.

But the last available data shows the Ministry of Labour and Employment continues to report a fraction of this number.

For the year 2010, this comes to 1,064 fatal accidents and 10,111 non-fatal injuries, which add up to 11,175 shop floor injuries across India.

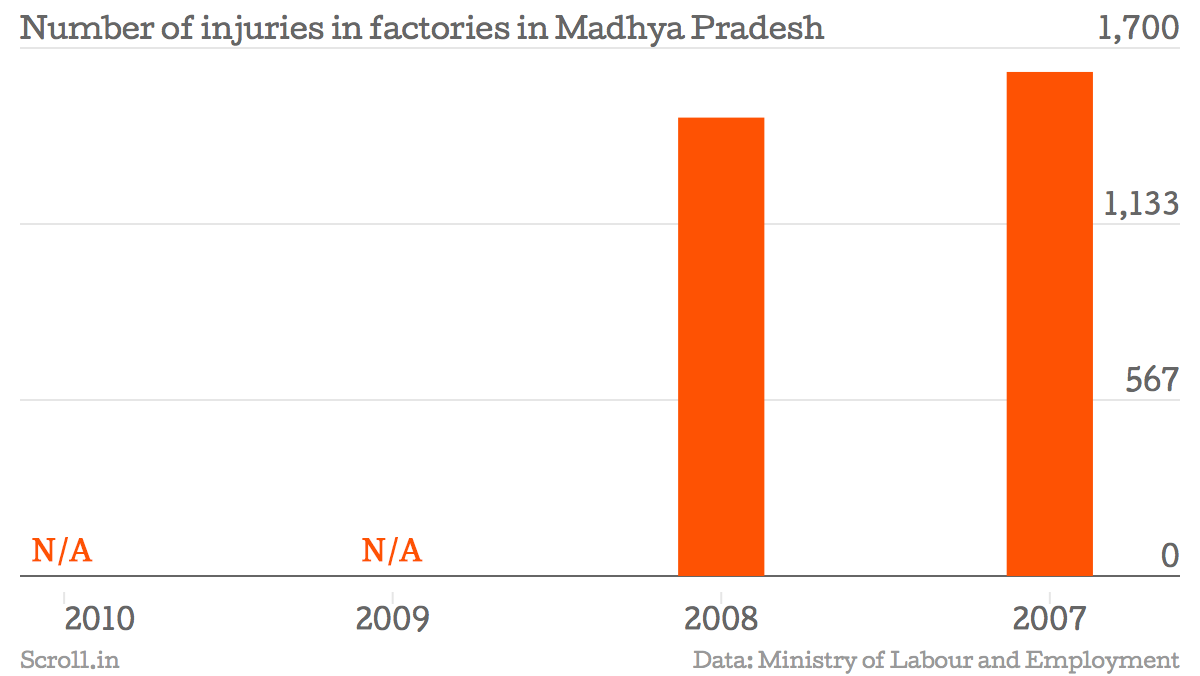

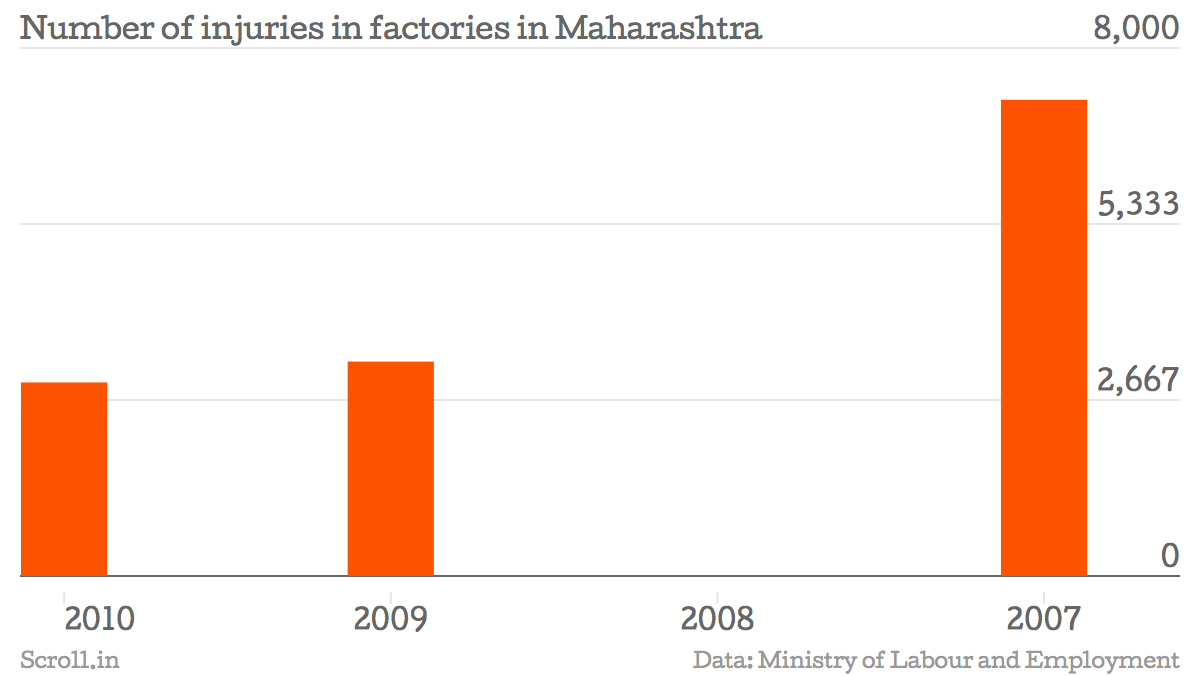

But a state-wise breakup of the data shows why the numbers are most likely gross underestimates.

Gujarat reported 2,992 injuries in 2010 but none in the previous three years.

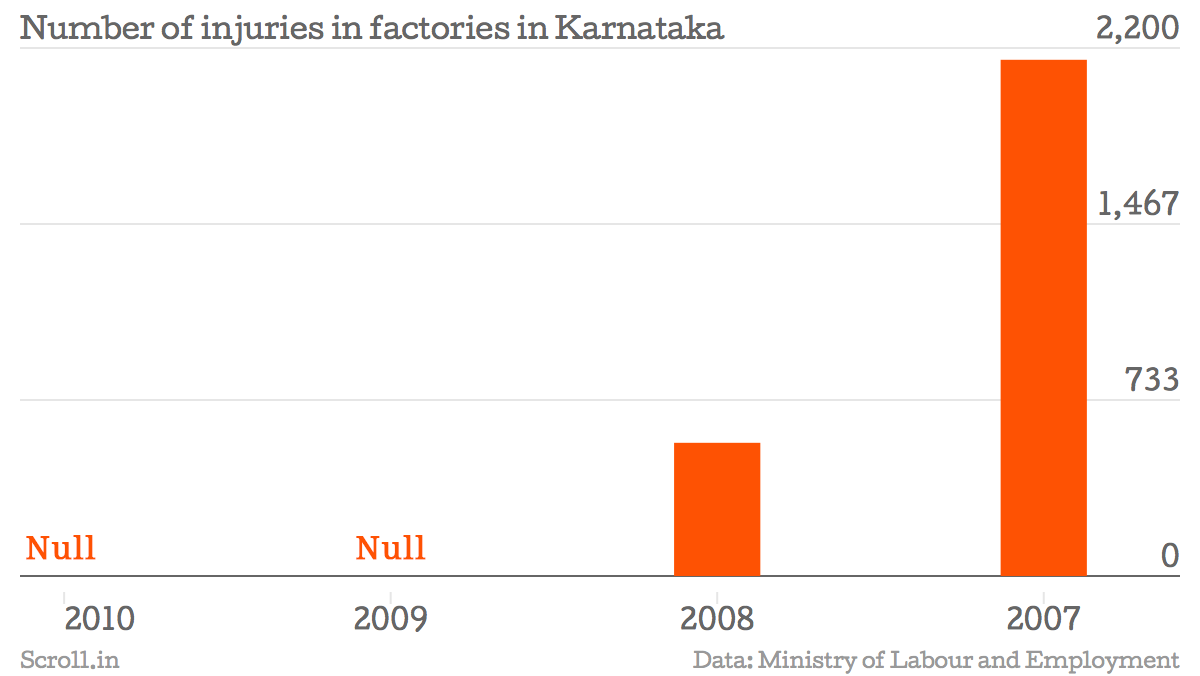

Several other states showed a similar pattern of inexplicable highs and lows.

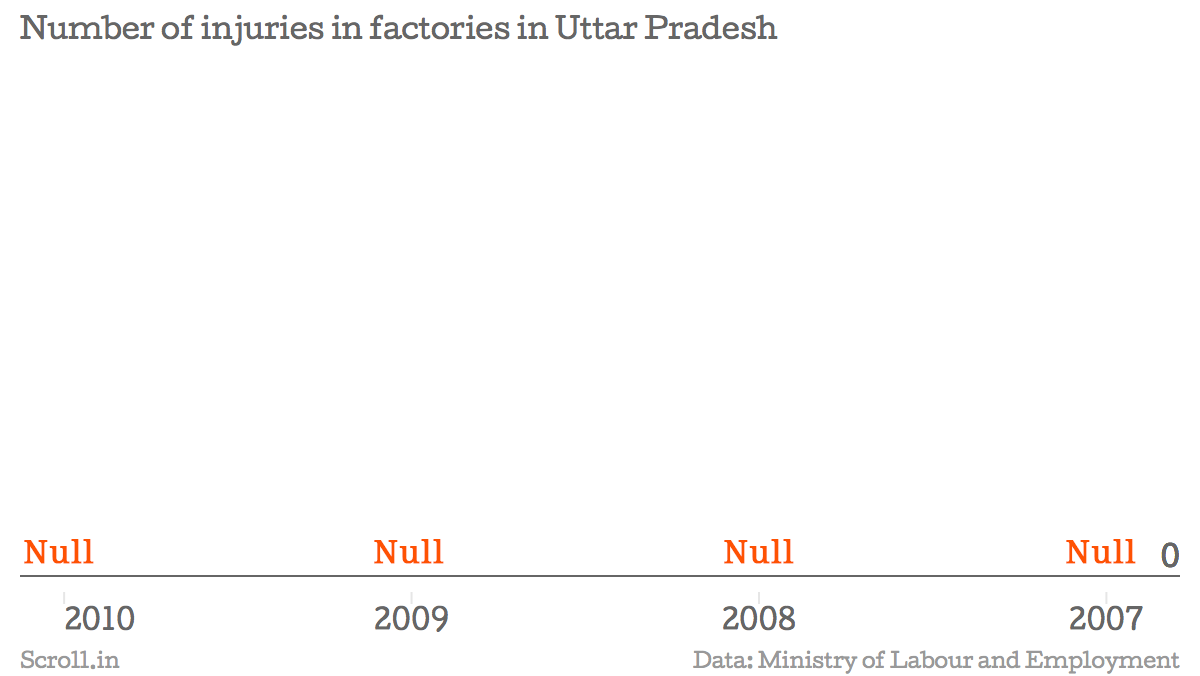

Uttar Pradesh reported zero injuries.

These numbers have been compiled by the Director General of Factory Advice Service and Labour Institute, which comes under the Ministry of Labour and Employment.

Another dataset of work-related injuries is prepared by the ESI Corporation when it gives out lifelong pensions to disabled workers and the families of those who perished in workplace accidents. In 2012-13, ESI received 16,282 applications for death and disability benefits.

But the ESI numbers are also likely to be underestimates, if the pattern Scroll found in the amputation cases among workers in the automobile industry of Haryana is common to other parts of India.

No takers for insurance

As the orthopedic surgeon at the ESI hospital in Manesar, Dr Pankaj Bansal sees about 20 daily cases of 'crush injuries', which result in broken fingers or amputated hands. But as a member of the ESI medical board which examines workers and verifies their claims, he saw just 12 cases in the whole of November. “Only a small fraction of those who come to us for treatment take the next step and file applications seeking benefits,” he said.

More than seven lakh workers are registered with the ESI Corporation's Gurgaon office. But this year, between March and November, the office cleared just 133 applications for disablement benefits.

Shivanth, an activist of the Garment and Allied Workers Union, said that the workers, most of whom are migrants from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, often go back to their villages after getting injured in factory accidents. “They are not able to pay rent since they are no longer able to work,” he said. “And they don’t have the resources to stay and pursue their insurance benefits.”

To apply for disablement benefits, Ram Babu Pandey first needs to get an ESI card. "I asked my employer to get me one," he said, "but he got angry and yelled at me, saying 'Why don't you trust me?'"

Speaking with Scroll on the phone, his employer, Anil Sharma of Narmada Polymers, denied that he had sought to conceal Pandey's injury. “I sent him to a private hospital to get him the best treatment,” he said. “As far as his ESI enrollment is concerned, he had joined just a day before his accident. We have initiated the process of enrollment with ESI.”

ESI officials say this is a common pattern where factory owners register their workers with the ESI only after an accident takes place, and often they don't even do that. Detecting such irregularities is difficult because the ESI office is short-staffed: 23 of the 30 posts of ESI inspectors in Gurgaon are vacant.

A systemic flaw

If the fight for benefits is uphill, the chance of a worker initiating legal action against his employer for negligence in safety matters is next to impossible. "The company makes one crore rupees a day. How can we fight it?" said Satish, who lost his son, Suraj, in an accident in October in a plastic auto-component factory in Bawal industrial area in Haryana's Rewari district.

Ideally, the onus of initiating action against a factory owner would not lie with the worker. The labour department would have access to hospital records to keep track of workers who report injuries. If a factory consistently shows up as a site of accidents, the labour officials could inspect its shop floor, carry out a safety audit, and prosecute the owners for safety lapses. R K Gautam, a joint director in the headquarters of ESI Corporation in New Delhi, said that the Ministry of Labour has mandated "exchange of information" between various agencies. But at the moment, there is no formal mechanism for a flow of information between the ESI Hospital, the ESI claims' office, and the factory inspection wing of the labour department.

Against this backdrop of an underreported crisis of safety in Indian factories, the Modi government has launched a campaign to encourage manufacturing in the country. "Why does Modi ji just talk of 'Make In India'?" said Jitender, a leader of the newly formed Workers Solidarity Centre in Gurgaon. "Shouldn't he also talk of Safe in India?"

This is the concluding article in a three-part series on industrial safety. All the articles are available here.