The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was a horrifying disaster that killed around 250,000 people. Coastal areas of Aceh, on the northern tip of Indonesia, were hardest hit and roughly 5% of the population of the entire province died.

Tsunami-related mortality in Aceh, Indonesia.

Elizabeth Frankenberg and Duncan Thomas, Author provided

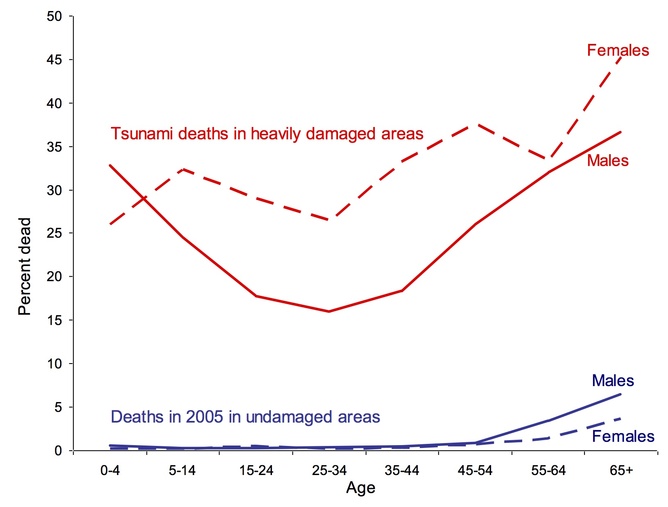

The figure above illustrates the mortality impact of the tsunami. Death rates in 2005 in areas that were not directly affected by the tsunami are in blue. The devastation of the tsunami is depicted in red, which reflects mortality in heavily damaged areas. In these communities, 30% of the population perished and rates reached 80% in some of the worst-hit communities.

Lost children

Death rates were highest among young children, older adults, and women in their prime (aged 25 to 45-years-old). Of course, strength and ability to swim were key for survival but, it turns out, household composition also mattered. Stronger members helped the more vulnerable. The more prime-age men there were in the household, for example, the more likely others were to have survived.

Sadly, many surviving parents lost children in the tsunami. Other parents, even those living in the same neighbourhoods, did not. Using data from the Study of the Tsunami Aftermath and Recovery (STAR) project, we examined how parents’ fertility decisions were affected by the death of a child in the tsunami.

Tsunami survivor Ahlan pays tribute to the child he lost in the tsunami.

The tsunami was completely unanticipated – there had not been a tsunami on mainland Indonesia for more than 500 years. The destruction and loss of life varied from one community to another because of different landscapes that affected the force with which the waves struck the shore.

The STAR baseline survey, which was conducted before the tsunami, includes both communities that were later heavily damaged and other comparable but relatively undamaged communities. The study is representative of the population living along the coast of Aceh before the tsunami and followed more than 30,000 survivors annually for five years after.

In our research, we estimated that in communities where the tsunami cost lives, fertility increased by almost three-quarters of a child in the five years afterwards. This is a huge impact and you can see the effects today, with more babies and young children in the region relative to teenagers and older adults.

Fertility boom

Who bore these children? Mothers who lost children in the tsunami were much more likely to have a child within five years of the disaster than mothers whose children survived. Adjusting for age, education and parity, and comparing women who were living in the same community at the time of the tsunami, the difference is 37%. But these new births account for only about 13% of the increase in total fertility.

Who else had children? We looked at women who had not had any children before the tsunami, most of whom were young. Among childless women, those who at the time of the tsunami were living in communities where the disaster took lives were more likely to have children in the five years after the disaster than similar women in communities where there weren’t deaths from the disaster. The fertility gap was larger the higher the tsunami-related mortality was in the community. Those women in affected areas shifted their child-bearing to an earlier age, and this accounts for the majority of the overall increase in fertility.

Rebuilding

So, the post-tsunami fertility boom was driven not only by parents who lost a child but also by others in the devastated communities who contributed to rebuilding after the devastating disaster.

Nasrul Affan with his new family in 2014. He lost a wife and two children in 2004.

This is apparent across Aceh where there has been tremendous rebuilding of homes and livelihoods. Families responded in all sorts of ways. Men who lost their wives and children re-married and started new families. Extended families and communities rallied to help young children who were orphaned by the tsunami. How will all this work out over the longer-term? We will find out as we continue to follow the lives of the STAR respondents.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation.