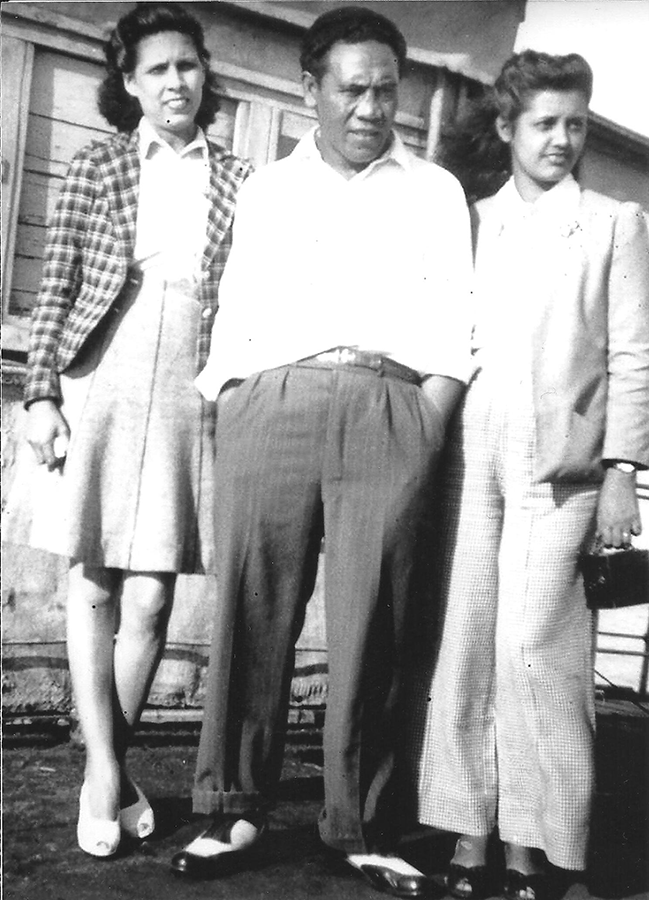

On Wednesday night, Penina Partsch posted an item on Facebook announcing the death of her grandmother, Bridget Moe in Houston, Texas. This photo shows Partsch and Moe in 2011, as they were preparing for the older woman's 85th birthday. Partsch had cooked up an enormous meal, made elaborate decorations and and edited a slide show about her Nani’s amazing life. And what an eventful life it had been. Bridget Moe, born Bridget Althea Ensell to an Anglo-Indian family in Calcutta, was the last living link in an unlikely cultural loop that connects India to the South Pacific islands, a connection that has enriched Indian music immensely.

This loop was strengthened immeasurably in 1929, when a Samoan guitar player named Tau Moe, who had grown up in Hawaii, stopped by in Calcutta for the first time. He would return a decade later, and stay much longer. Moe was a master of the Hawaiian guitar, which is placed horizontally, often across the musician’s lap. The strings are plucked with one hand, as with conventional guitars. But instead of picking out chords with the other hand, Hawaiian guitar players change pitch by sliding metal or glass bars across the strings, giving the instruments its distinctive sound. The slides are sometimes called “steels”, which is why Hawaiian guitars are also called steel guitars.

Tau Moe – or Papa Tau, as he was known – started his musical career as a schoolboy, playing at a stage show in Honolulu for passengers who had stepped off their cruise ships. In 1927, when he was 19, he met his future wife, Rose, at a steel guitar class. Later that year, they joined a music troupe that had been hired to do a South Pacific musical show in the Philippines, setting off on a voyage that would keep them away from Hawaii for 60 years.

Over the next few years, they played Hawaiian music in Japan and China. They even did a stint at the Taj in Bombay in the 1930s before heading to Berlin, where they met Hitler at a fundraiser for orphans. The 1940s found them back in India and they spent almost all of the Second World War in Calcutta, playing at the Grand Hotel. “We played Glenn Miller arrangements (or my own) but always included Hawaiian music,” Moe told one interviewer. “We would do a session of jazz band music, then some classical music, then a Hawaiian session with me on steel guitar.”

The couple’s son, Lani, who had been born in Kyoto, choreographed the shows, in addition to singing and dancing with the band. Their daughter, Dorian, was born in Calcutta in 1946 during a burst of intense Hindu-Muslim rioting. The Moe family would later start performing as the Aloha Four.

At some point during his stay in India, Moe met Mahatma Gandhi. “He was a very highly educated man and I enjoyed the 35 minutes were spent talking to him,” Moe told one interviewer. The musician thought that Gandhi’s dhoti was similar to the lava-lava worn by Pacific Islanders, but told the political leader that it was unusual to see the garment tucked between the legs. “He laughed and said, ‘Well, I am better off than you Polynesian people who walk about without shirts,’” recalled Moe.

During Tau Moe’s stay in India between 1941 and 1947, he taught several Indians how to play the steel guitar, most notably an Anglo-Indian musician named Garney Nyss. Nyss would later form a band called the Aloha Boys and would go on to cut more than 60 records. In the 1950s, the Hawaiian guitar became a familiar sound in Hindi film tunes. Tau Moe died only in 2004 and continued to perform until late in his life. Here’s a record he made in Calcutta in 1943 with the African-American pianist Frank Shriver, who went by the stage name Dr Jazz. Lani Moe is among the vocalists.

Paducah by naresh.fernandes

The Aloha Boys.

Though Tau Moe was the most influential steel guitar player in India, he wasn’t the first to bring Hawaiian music to India. In 1922, a seven-member group named Ernest Ka’ai and his Royal Hawaiian Troubadours presented a show called A Night in Honolulu at the Excelsior Theatre, performing hula hula dances wearing yellow wreaths. They came several times over the next few years. By the time they returned in 1928, The Times reported, “Bombay has many lovers of Hawaiian music and there is for these, and indeed for anyone who loves good music and singing and dancing, a treat in store when Mr Ka’ai’s Troubadours open in Bombay on November 30.”

Everyone seems to need someone to exoticise. Somehow 1930s India, the country others saw as a place of snake charmers and opulent maharajas, chose to be captivated by women in grass skirts swaying under fake palm trees. In 1930, a group called the Royal Samoans visited Bombay. The correspondent of The Times of India was bowled over by the spectacle they put on at the Empire Theatre. “The dress (what there is of it) of both men and women reminded one of the pictures of the ancient Egyptians,” the paper wrote. “They are unlike anything India has seen before.”

Bombay seemed to be fascinated by the South Seas. The next year, one Mrs Hayes of Jasmine House on Convent Street in the Fort was offering Hawaiian guitar lessons at Rs 30 for four classes a month. Furtado’s music store, meanwhile, was offering Hawaiian guitars – “sweet toned and good finish”, their ad promised – for Rs 28. The price included a canvas case. In 1932, at a fundraiser at Bandra’s St Andrew’s School, right down the street from where I live, the repertoire included “an excellent replica of Honolulu’s coy maidens dancing the hula hula, enlivened by song”, said the Times.

Back in Calcutta, Tau Moe had by the 1940s been joined by two of his cousins: Pulu and Tauivi Moe. Tauivi Moe began to perform at the 300 Club, where he met a young Anglo-Indian singer named Bridget Ensell. They were married when she was still in her early teens, though, her granddaughter Penina said that they didn’t start living together until she was 18. In 1944, Tauivi Moe’s husband introduced her to the African-American pianist Teddy Weatherford. Evidently, Weatherford’s band at the Grand Hotel was receiving mixed reviews at the time, mainly because his singer wasn’t up to scratch. Tuivi Moe told the pianist to “try out his wife” because she had “a lovely voice”. It was a fit and she ended up making a couple of records with the Weatherford band, in addition to singing with them at the Grand.

Tauivi and Bridget Moe headed for Samoa in 1949 and moved to Hawaii in 1956. Neither of them sang professionally after that. Tuivi Moe became a masseur at the YMCA, while his wife became a manager at a shop called India Imports. When their daughter, who was living in Houston, was expecting her first child in 1977, the couple moved to Texas and ended up staying. Tauivi Moe died in 1980.

Though I’d read a little about their famous cousin, I discovered the story of Tauivi and Bridget Moe only three years ago, when their granddaughter Penina Partsch wrote to my friend Suresh Chandvankar of the Society of Indian Record Collectors wanting to know if he had any of the records he grandmother had cut with Teddy Weatherford. If Bridget Moe had actually put any copies of the records in her baggage when she left Calcutta, they’d long been lost.

Chandvankar passed the message on to me – and as it turns out, I did have one track. I mailed Partsch Ice Cold Katie. The next morning, I had a message in my inbox. “You can imagine my excitement when I receive emails about the Ice Cold Kate track!” Partsch wrote. “I am still reeling from the shock. I played it for my sister living in Hawaii (who is incredibly homesick as it is) and she cried and cried.”

Ice cold katie by naresh fernandes

Here's a grainy amateur video of a performance by the Tau Moe family.