A silent transformation has been taking place in two gram panchayats (village councils) in Karnataka’s Oorkunte Mittur, Kolar district, and Dibburhalli, Chikkaballapur district, over the past four years.

Karnataka is considered a champion in decentralisation; it is among seven of 30 states that has devolved all 29 functions to the level of the panchayat. In many others, these powers still rests with the state government.

The panchayat office, once dormant, now buzzes with activity. A monthly monitoring system has been instituted for the gram panchayat to oversee its annual village-development plans. Mandated committees, such as the Bal Vikas Samiti (children’s development committee) and School-Monitoring Committee, which were near defunct, have begun meeting diligently to monitor overall child development.

For citizens, change has come by way of better public services.

Villages under the jurisdiction of these two Gram Panchayats now have functional street lights. Ration shops display mandated information about the public distribution system (PDS), the subsidised-food network. Officials are available 24×7 to resolve citizens’ complaints related to water.

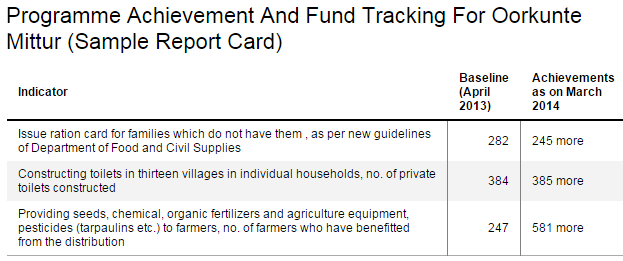

In 2013-14, the Oorkunte Mitturgram panchayat constructed the highest number of toilets under the erstwhile Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan, a national programme to build toilets.

Much of this systemic change has been fuelled by an innovative framework, the Gram Panchayat Organisation Development (GPOD),devised by Arghyam, an NGO, and subsequently transitioned to the non-profit Avantika Foundation. The gram panchayats themselves contributed to creating this framework and adopted it for implementation in their villages.

The GPOD framework rests on the principle that gram panchayats inherently possess tremendous potential and can function as robust institutions.

Avantika Foundation has been working with these two gram panchayats to build their capacity in a systemic manner, by matching their vision to their mission, roles and structures, resources and incentives.

In Oorkunte Mittur for instance, panchayat members collectively articulated their vision as “overall sustainable development through transparent and good governance” and outlined corresponding mission statements.

Going by the management principle that responsibility can be shared, but accountability should lie with one individual, panchayat members assumed individual portfolios.

For instance, a portfolio was created called Head-Production, responsible for an umbrella of livelihood functions such as agriculture, animal husbandry and job programmes.This arrangement resulted in distributed leadership as against a Sarpanch-dominated system, and hence led to higher transparency in panchayat governance. Panchayat members who have clearly spelt out roles and responsibilities admitted to feeling a sense of ownership and accountability.

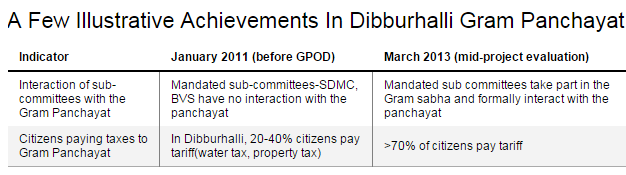

The alignment of all spokes of the administrative wheel resulted in service improvements, as we see below:

Source: Gram Panchayat Organisation Development-A process document, Avantika Foundation

Their success proved infectious, with 15 other gram panchayats in Karnataka coming forward to adopt this framework.

More recently, the government of Karnataka has adopted the GPOD framework for implementation in 30 gram panchayats, covering 450 villages in Kolar district’s Mulbagaltaluka, over the next two years. The objective is to improve last-mile governance. Indeed, it is sanctioned as the country’s first innovation project under the Rajiv Gandhi Panchayat Sashaktikaran Abhiyan (panchayat strengthening scheme)

“Potentially, with the funds that they have and can leverage, the powers they can exercise and the people resources they can recruit and access, gram panchayats should be able to change the face of rural India,” said Sonali Srivastava who heads the Centre for Decentralised Local Governance, Avantika Foundation, which is spearheading the Mulbagal initiative.

“We need to recognise the contributions, which elected members can make, and create enabling environments and incentives for them to function effectively,” said Srivastava.

“The project promises to inject more institutional efficiency into gram panchayats and will serve to enhance citizens’ faith in the panchayati raj system. It will act as a great boost to decentralization,” says director-Panchayat Raj, Government of Karnataka, S. M. Zulfikarulla.

From fumbling novice to seasoned administrator

Viewed from the bottom-up, gram panchayats are often ill-equipped to manage the responsibilities handed down to them.

“When elected for the first time, five years ago, I had no clarity about Panchayati Raj institutions or the expectations of my role,” said Bharati (she uses only one name), a gram-panchayat member from Oorkunte Mittur gram panchayat in Karnataka.“The anganwadi (creche) was right next to my house but I never bothered to visit it.”

Bharati, a gram panchayat member from Oorkunte Mittur in Karnataka narrates her experience of being elected to the Gram Panchayat for the first time. Source: Avantika Foundation

She narrated an anecdote about how she was once invited to address school teachers. “I was so unaware about panchayat functions and duties that I ended up talking to them about anganwadis,” said Bharati, “without realising that the subject did not concern them at all.”

Bharati benefited from the organisational development of her panchayat and the delineation of her role. She took on the social-justice portfolio, which encompassed functions of nutrition, food security and complaint resolution.

“I gained tremendous confidence about my roles and responsibilities,” she said. “I am particularly proud about the drastic improvement in the midday meal scheme that I was able to bring in.”

The quality and quantity of the meals got a boost. There were instances of food being siphoned which led to an investigation and subsequent correction by the department of food and civil supplies.

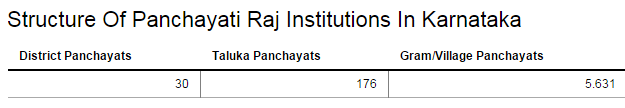

Bharati’s gram panchayat is among 5,631 village bodies in Karnataka that are going to the polls this year. But like her, most gram-panchayat members lack the ability and information to handle their roles.

Source: www.lgdirectory.gov.in, National Informatics Centre

The Panchayat story

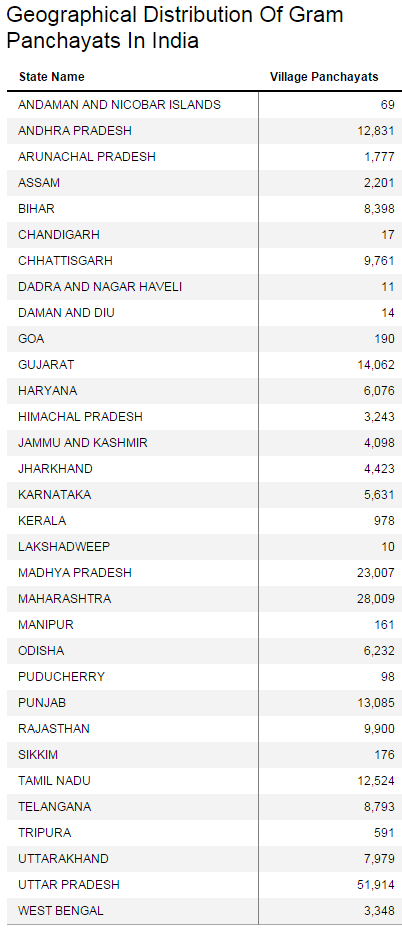

The challenge however, isn’t unique to gram panchayats in Karnataka. There are nearly 239,000 gram panchayats across India; many suffer from poor decentralisation of funds, functionaries and functions.

Source: Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India

The Ministry of Rural Development has an annual budget of Rs 80,043 crore, of which the Panchayati Raj Ministry has an allocation of Rs 7,000 crore.

As local self-government institutions, gram panchayats are vested with tremendous responsibility, under the Constitution 73rd Amendment Act, 1992.The move was meant to overhaul the era of centralised planning and bring governance closer to people.

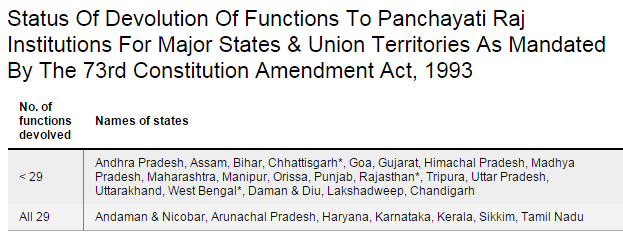

The Eleventh Schedule of the Constitution thus devolved 29 administrative functions to the level of the gram panchayat, including health, education, drinking water, sanitation, rural housing and agriculture.

Source: As presented by former Minister of Panchayati Raj Shri V. Kishore Chandra Deo in a written reply in the Rajya Sabha, December 2012–http://www.pib.nic.in/archieve/others/2012/dec/d2012121302.pdf, *Note: Delhi has no panchayats. Data related to J & K and Jharkhand is not clear. Mizoram, Meghalaya and Nagaland are exempt. Independent reports claim Chattisgarh, Rajasthan and West Bengal have subsequently devolved all 29 functions, but this could not be verified.

Gram panchayats also perform many duties beyond the administration of these functions. They play a crucial role in implementation of several centrally-sponsored schemes, including the Indira Awas Yojana (rural housing programme), Integrated Child Development Services, National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme and National Rural Health Mission.

The village panchayat also has its routine responsibilities in terms of undertaking annual village planning,addressing usualcitizens’ grievances over water shortage or malfunctioning ration shops,organisation of ward committee meetings, and tax collection.

But as the examples of Oorkunte Mittur and Dibburhalli show, gram panchayats certainly need much organisational strengthening before they achieve Gram Swaraj (village freedom) in its true essence.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.