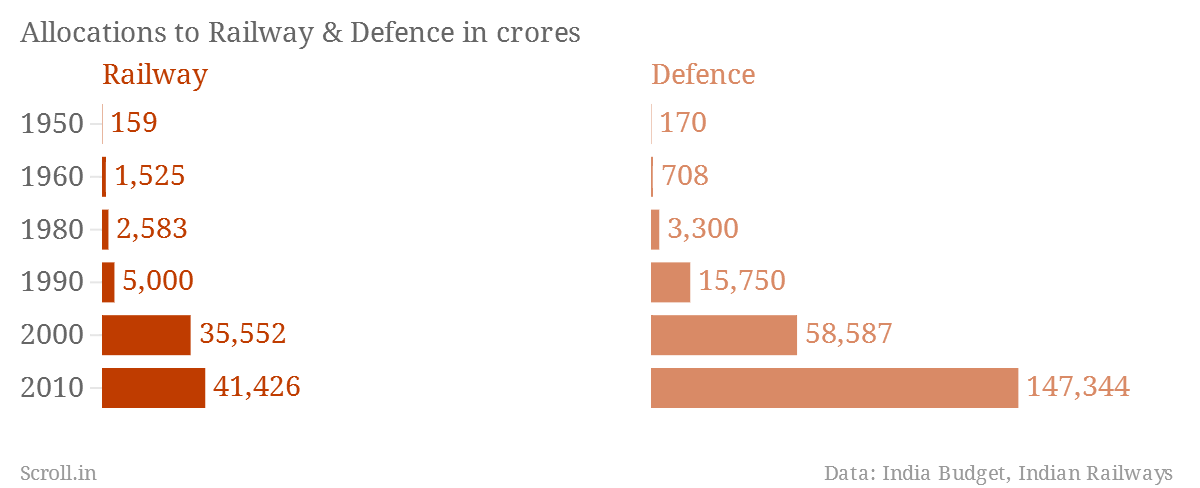

At the time, the railways commanded close to three-fourths of the government’s budget and transported a huge share of people and freight. Having a separate accounting and budgeting procedure made sense. Today, India’s trains don’t even come close to that level of influence – they lost the people-and-goods carrier crown to road transport decades ago. It also no longer dominates government spending, with subsidies and ministries like defence taking a much bigger chunk.

From commanding three-fourths of the budget, as the railways did during the Raj, they now clock in at under 4% of overall expenditure. Yet, this alone does not mean India has to end a tradition that has been around for nine decades now.

Since the 1990s, the railway budget has earned as much attention as the union budget, while the Economic Survey of India, which is more important than the former, at least, is sandwiched in between and often lost in the din.

The railway ministry is usually accorded to one of the biggest alliance partners of the leading party in the central government. They have offered a useful way for regional politicians to get noticed, as Lalu Prasad Yadav and Mamata Banerjee showed. This has also meant the railway budget often conforms to more populist tendencies, and accountability, compared to other ministerial budgets.

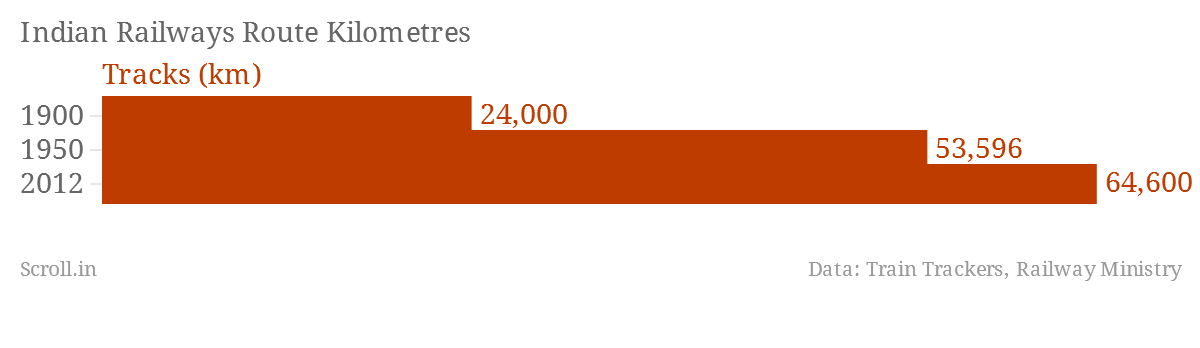

The railways have substantially fallen behind as a mode of transport, thanks in part to a spurt of road construction projects over the last few decades, but also because they reached capacity without building additional supply. In terms of tracks alone, railway growth in India hasn’t been terribly impressive.

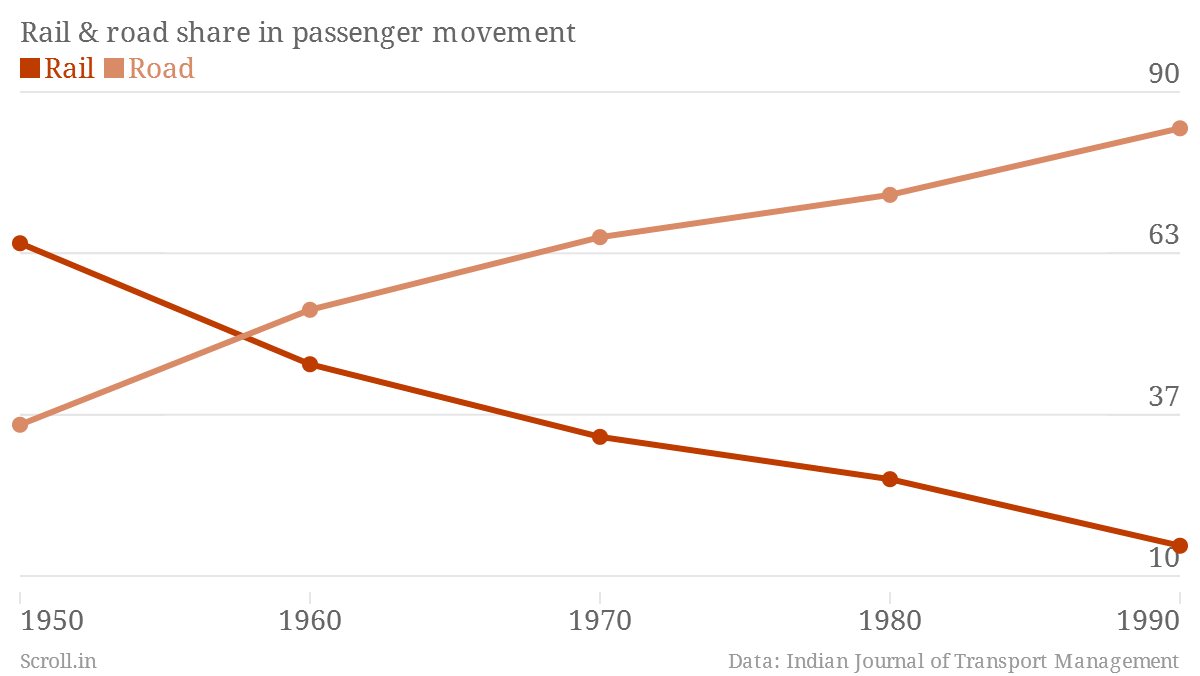

Even if there might not be need for much more in the way of tracks, both electrification and modernisation have lagged. Even simply upgrading the tracks, locomotives and coaches will allow the railways to compete with roads again. From carrying around 35% of all passenger traffic in 1950, roads now ferry 85% of passengers around the country. As Indian roads continue to improve and the Volvo buses continue to proliferate, it’s hard to see this trend changing.