Research has long shown that the news media report on a world in which men outnumber women in almost all occupational categories – with the exceptions of homemaker (72% female) and student (54% female).

Women in the news are identified by their family status four times as often as men – and by age almost twice as often. When a woman is interviewed, it is most likely to be as an “ordinary” person speaking about her personal experiences: 80% of experts quoted in news stories are male.

These figures are taken from the 2010 Global Media Monitoring Project, the largest and longest study of gender in the world’s media. Every five years since 1995, the GMMP has taken a snapshot of the world’s news media on one ordinary day.

It spans press, television, radio, and since 2010, internet news. Volunteers record a proportion of their country’s news media on that day to find out who “makes” the news: who is doing the reporting and who is being reported.

Unsurprisingly, the research has consistently shown that women are underrepresented and that this pattern is maintained across all participating countries. Progress has been made in some areas: between 1995 and 2010, the percentage of female news subjects rose from 17% to 24%.

Where women appeared in only 7% of stories about politics and government in 1995, by 2005 this had risen to 19%. By 2010 women were reporting 37% of the world’s news (up from 28% in 1995). But at this rate of change, it will take at least another 40 years to achieve parity.

Thousands of volunteers in more than 100 countries took part in the fifth Global Media Monitoring Project this week. Over the next weeks, this army of volunteers – drawn from grassroots groups, activists and academics from Argentina to Zambia – will be analysing the material we have gathered, using the same pre-agreed system.

A project like this can only ever offer a snapshot of where women can be found in the global news media. But that snapshot is nonetheless powerful. The first GMMP reported as part of the NGO forum of the UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995.

The Beijing Platform for Action at the conference recognised women’s role in the media as one of 12 areas for action to establish equality – alongside areas like poverty, education and training, violence against women, and health.

Overseen by the World Association for Christian Communication, the GMMP results themselves are usednationally and internationally to campaign for change. But the means of gathering the data is equally important. By bringing academics and activists together, training volunteers, and making the research instruments freely available online, the project itself becomes a learning tool.

This year, I’m co-ordinating the GMMP research for Scotland, working with a team of my gender studies students. With Nicola Sturgeon as first minister, one part of the UK has both a female leader and gender-balanced cabinet for the first time since the project began. So we’ll be able to explore whether this makes a difference to political news practices in Scotland and, indeed, the rest of the UK.

Sexism alive and well

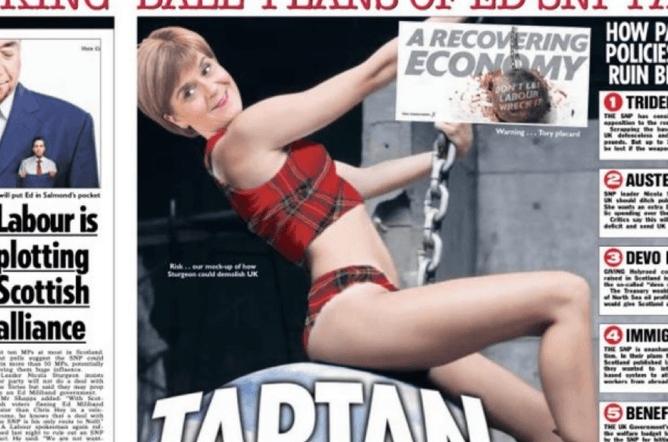

Over the past few weeks we’ve seen a number of controversial representations of Sturgeon – most notably The Sun’s sexualised mock-up of her in a tartan bikini astride a Miley-Cyrus-esque wrecking ball. We’ve also seen widespread reporting of the online homophobic abuse directed at Ruth Davidson, the leader of the Scottish Conservatives.

How The Sun wants us to think of Nicola Sturgeon Daily Record, CC BY-SA

These stories, among many others, suggest that sexism is alive and well both in politics and in political reporting. But the widespread condemnation of these incidents across the political spectrum – and the extensive and critical media coverage they received – also demonstrate that the news media can be proactive in challenging “everyday sexism”.

With the significant growth of “fourth-wave” feminist activism in the UK since the last monitoring exercise, it will be interesting to see if the 2015 findings show an increase – from 6% in 2010– in the percentage of stories explicitly dealing with gender inequality.

While it is improbable that the 2015 global report will reveal gender parity in news coverage, it will certainly open up a space to debate these issues. It offers a challenge to all of us to think critically about gender in our news media, to recognise implicit (as well as explicit) media sexism and to be part of the movement for challenging it.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.