Jatav's death as recorded as an accident by the police in Alwar, the district that borders Dausa, where Singh's village lies. The police did not explain why Jatav had left home in the middle of night to go to the isolated railway tracks. “It was a kilometer from the field where we have planted kan [onion saplings],” said Sonu, Harsukh's son, a student at the Industrial Training Institute in Alwar. "There was no reason for him to go that side." Sonu has asked the administration to record his father's death as a suicide. As the reasons that drove Harsukh to take his life, his son cited the multiple loans this father had taken and the damage to crops from the recent hailstorm.

Most farms in Alwar, along Rajasthan's northern border with Haryana, are satisfyingly fertile. Mango, neem, sheesham trees grow abundantly. The land can support multiple crops. Two-thirds of the farms have steady water supply from wells. Alwar's 2,200 villages have been spared of the droughts frequent in central and southern parts of Rajasthan. However, last month's hailstorms ravaged the winter crop of wheat and vegetables.

Despite this terrible destruction, though, Jatav's death elicited surprise. “This has never happened before,” said Virendra Vidrohi, a social activist with Indian Social Action Forum. "Farm distress has been growing for several years but this is the first time we are seeing farmer suicides in Alwar."

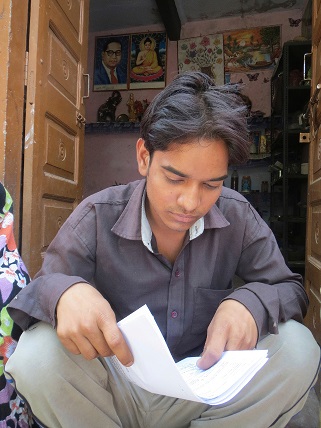

Hasmukh Jatav's son Sonu, 20, a student at Industrial Training Institute, Alwar.

Deadly hailstorm

Harsukh Jatav worked as a sharecropper in Tulehra, on the outskits of Alwar town. It is among the 231 villages in Alwar where hailstorms destroyed the entire crop in March. Not only did the hailstones flatten the crops, they pounded holes in metal sheets and pipes. “At around 6 30 pm, we were cooking dinner when olavrishti [hailstorm] started,” recounted Leelavati Yadav, a farmer in her 50s. “We took cover inside as the hailstones, bigger than my palm, fell for over half an hour. When it got over, the wheat was covered upto several inches with the hail. We could do nothing that night to save the crop. We stood crying, looking at the fields.”

A plastic pipe carrying drain water along the walls of Yadav's pucca house, metal screens over the windows, plastic water tanks stored on the roof – all had been perforated by the force of the falling hailstones. Elsewhere in the village, the mud on the walls of Jaitun Begum's house peeled off as the hail fell. Another farmer, Dhauli Gujjar, showed the injury marks on her cattle.

After the hailstorm, it rained for the next three days. Once the rain stopped, the farmers rushed to cut the crop, hoping to salvage a little grain and fodder. But the sudden spike in demand for farmhands led labourers to ask for Rs 350-Rs 400 as wages, double the existing rate. This would have run into over Rs 1,000 rupees a day per bigha (a fourth of a hectare). As a result, many small farmers set fire to the fallen crop.

Chitar Mal Jatav says he had leased 4.5 bigha of land for two years for Rs 60,000. He had spent Rs 25,000 on buying inputs for the wheat crop that he set afire to last week. “My plot is along the drain carrying sewage from the city,” said Chitar Mal Jatav, who works as a para-teacher in Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan. "First the hail destroyed the crop, then the fields remained logged with water and sewage for days. I could not save anything."

He recounted that BJP MLA Srijairam Jatav accompanied the patwari (revenue official) the next day to the village to survey the damage. “The assembly was in session, the debates went on and on. Then, the Chief Minister left for Japan,” said Chitar Mal, referring to CM Vasundhara Raje's five-day visit to Tokyo on April 7 to seek Japan's participation in the upcoming Resurgent Rajasthan partnership summit. Many farmers saw that as a sign of the chief minister's priorities.

Chitar Mal Jathav, who had leased 4.5 bighas of land in Tulehra village, sets his ruined wheat crop on fire.

High-intensity farming

Most farmers with average landholdings recount the old practice leaving a third of their plots fallow for the soil to regenerate. Until a few years ago, they said, they supplemented fluctuating crop incomes with grazing cattle and goats. But in recent years, common grounds around Tulehra that served as pastures have been built over. With increasing pressure on land, there is a shift towards high-intensity farming even as most farmers admit they can barely afford the cost of the inputs.

The cost of leasing tractors, fertilizer, harvesting, threshing and transporting the wheat crop grown on a bigha of land works out to Rs 10,000 to Rs 12,000. The returns in the best-case scenario: a yield of 16 quintals wheat per bigha, which would fetch upto Rs 20,000 from sale of grain, at the rate of Rs 1,200-Rs 1,300 per quintal. Wheat straw sold as fodder fetches another Rs 4,000. If the weather remains favourable, a five-member household could earn Rs 14,000 over five months ‒ not enough to result in any savings to tide over future uncertainties and barely enough to sustain these input-intensive practices of farming.

The dependence on fertilizers was most apparent last winter, when a shortage of urea led to fights at dealer shops. Urea bags were eventually sold under police supervision in an open ground outside the Sadar police station in Alwar in December.

The most vulnerable

In the precariousness of input-intensive agriculture, Dalit farmers like Harsukh Jatav bear the worst of the burden. Most of the land in Tulehra is owned by Yadavs, Gujjars and the Muslim community of Meos. Many Dalit farmers work as share-croppers to grow foodgrains to supplement their income from wage labour in the town.

When Jatav died, he had been a share-cropper for several years on Ramesh Yadav's land. With no land or capital of his own, Jatav had entered into a complicated system of crop-sharing over 12 bighas in which his share varied from crop to crop: half share of the onion crop over 0.7 bigha, a third of the brinjal crop over two bighas, and a fourth of the share of the wheat sown over 10 bighas of Yadav's land. While Yadav owned the land and the means of irrigation, Jatav provided the labour. They split the cost of inputs as per their crop share.

The past year had been a difficult one. Delayed rains in September resulted in last season's monsoon-fed crop of bajra oilseeds turning bitter. In January, disease finished the winter brinjal crop. Then, in March, as hail fell over Alwar, Jatav watched his wheat crop being destroyed. His share of the wheat crop after months of labour came to 12 quintals, worth Rs 15,600. When he died, Jatav had loans totalling over Rs 1.1 lakh from Yadav and his own relatives – at an interest rate of 36% – as well as from self-help groups. Since providing labour was part of his responsibility, when the crop began to rot, Jatav had no choice but to hire four workers paying them Rs 9,000 over four days to salvage his investment.

“For 30 years, I have worked in the same share-cropping system as Hasmukh,” said Ratti Ram, Hasmukh's cousin who works the land of Ramesh Yadav's younger brother's land. "We get nothing from it."

Remarked Kailash Gujjar, a farmer sitting nearby, "It is a system designed to keep the community in their place. It is almost like bandhua pratha [bonded labour].”

Jaitun Begum's home was damaged in the hailstorm.

Neither relief, nor compensation

On April 8, Prime Minister Narendra Modi increased the amount of compensation to farmers who have suffered crop loss due to natural disasters and relaxed the norms for claiming relief. Farmers who suffered upto 33% of crop damage have been made eligible for relief – the previous level had been a loss of 50%. Compensation for areas with assured irrigation such as Alwar has been increased from Rs 9,000 to Rs 13,500 per hectare, subject to a cap of two hectares per farmer. This amounts to a rise of 50%.

On the ground, in villages such as in Rajasthan, this translates into a compensation of Rs 3,300 per bigha, with an upper limit of Rs 27,000. But the amount does not cover the costs of seeds in most instances, or the labour expenses that even small farmers incurred in hurriedly cutting the crop. Sharecroppers such as the Jatavs need the consent of bigger farmers to prove a claim.

The prime minister has claimed credit for the single-largest increase in compensation since Independence. "Never before have compensation amounts been increased 1.5 times at one shot," said Modi. He could be right. As far back as most officials in Rajasthan can remember, until February this year, the compensation had been only Rs 2,200 per bigha. “It has remained Rs 2,200 per bigha at least since 1982 when I joined government service,” said Alwar's additional judicial magistrate Kunj M Sharma. Accounting for inflation, Rs 2,200 in 1982 prices would be equivalent to Rs 20,209 now, an increase of 9.2 times or 820%.

“It is not compensation,” said Sharma. "It is only anudaan (relief)."

Haji Munna Khan examines the damaged wheat crop in Tulehra, Alwar.

All photos: Anumeha Yadav.