The problem was highlighted last week by a parliamentary panel which wanted to know why it has been so hard to find suitable candidates for faculty positions in major universities. It even suggested that India might need a complete overhaul of the way it evaluates scholars.

“The Committee would like to have a evaluation report, if any, about the quality and standard of PhD holders across the country to understand why suitable candidates are difficult to find for the vacant positions," the standing committee on human resource development said in its report tabled in the Parliament last week. "May be we need to reorient the entire system of evaluation of PhD and other research scholars.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi pointed to the importance of research at the Indian Science Congress 2015 in January. "Our scientists should be able to explore the mysteries of science and not get stuck in government procedures," said Modi. "We have to place the university system at the cutting edge of the research and development activities in the country."

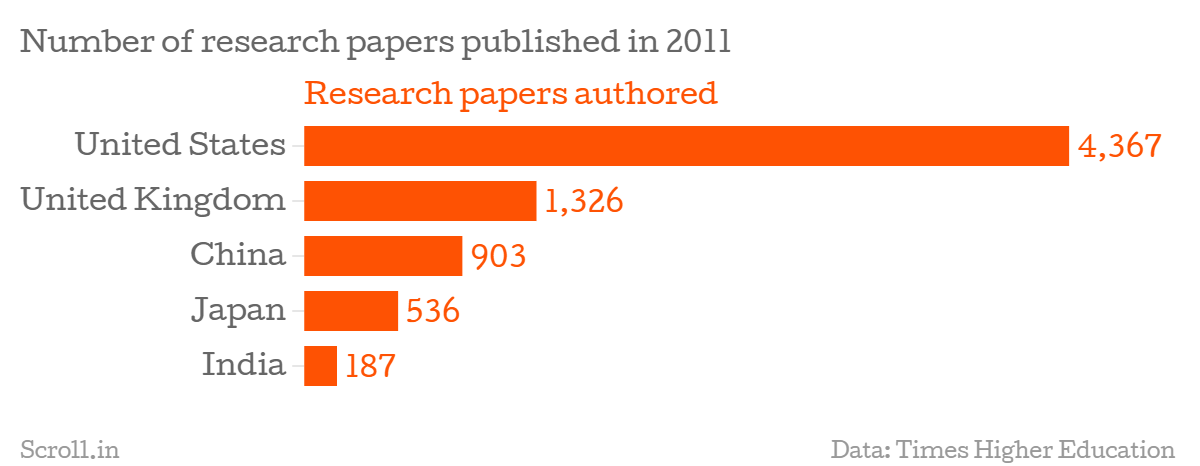

Another report by the British Council last year pointed out the same concern that India only produces a small fraction of PhDs as compared to countries like China and the US. “With a very low level of PhD enrolment, India does not have enough high quality researchers,” it said in its report.

It further went on to say that India is not producing enough PhDs since very few students go on to do research degrees compared to other countries and “only 140,000 (1%) students are enrolled as postgraduate researchers.”

Missing quality

While the report pointed out that India is missing researchers, a deeper concern comes from the quality of those who already hold or are pursuing PhDs. A recent report in FirstPost pointed out that one need not spend five years or so pursuing studies and research in India when the neighbourhood photocopier guy could arrange a thesis in less than five minutes for a few hundred rupees. Pay a bit more and the end product will escape most plagiarism detecting software.

While plagiarism is a common phenomenon in the Indian education, many are concerned about the lack of quality infrastructure places. “We don’t have quality PhDs in India because we don’t have enough quality PhD programmes or quality universities to groom those getting the degrees,” said Pratap Bhanu Mehta, President of Center for Policy and Research. “A PhD from an Indian university could mean anything since there are no benchmarks or quality controls for making sure that the PhDs people receive are of a certain quality.”

Echoing this, Shaswati Mazumdar, professor at the University of Delhi’s department for Germanic and Romance studies said that the government is making no efforts to keep people interested in pursuing research. “If you want people to take up research, you should give them incentives in terms of salary, grants, access to libraries and so on but that’s missing completely,” she said.

Mazumdar is not off-target here as scholars at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore wore armbands in February during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to demand an increase in stipends. The Department of Science and Technology reacted and raised stipends by about 55% but the scholars are yet to receive their hiked stipends and many are unsure about the actual amount they would get.

Promoting research

Even as the HRD ministry tries to fill vacancies and coax people into research, the committee report criticised falling budgetary allocations and advocated more funds to be pumped in. The committee observed that the overall budget for the Department of Higher Education has taken a fall of almost Rs 800 crores in 2015-2016 as compared to last year. “Moreover, this reduced allocation of funds does not match with the objectives of Twelfth Plan regarding expansion and growth of Higher Education Sector in the country and that this is also in contrast with the main objective of the improvement of access along with equity and excellence in higher education,” the committee noted.