This is not a case in isolation as continued discrimination against children from the social and religious minorities has prevented them from attending school or dropping out midway. Even more worryingly, as per surveys commissioned by the government, almost 75% of the students who are not in school belonged to the marginalised communities such as the Dalits and the Adivasis.

Most conversations around Indian education start with the fact that free and compulsory education is a fundamental right in the country with over 287 million illiterate people at the last count. The Right to Education Act was enforced five years ago, with the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh claiming that all children irrespective of social or gender category will have access to free education.

However, two years after the deadline of April 1, 2013 for implementing the key provisions of RTE, the ground reality remains grim. Official figures, however, claim some improvement by pointing out that only six million children remain out of school and the drop-out rate in schools has started showing a drop in the primary schools at least.

However, much remains to be done to achieve the goal of an inclusive education as the children who are out of school mirror the image of the same inequality that this rights-led approach to education set out to fight. Three out of every four children out of school are either Dalit, Muslim or Adivasi, according to the National Sample Survey Estimates from a report prepared last year by the Social and Rural Research Institute.

On the margins

With RTE’s focus on inclusivity and access, it was hoped that the poorest of the poor and the marginalised communities, which had so far shied away from sending their children to school for financial and cultural reasons, would jump on board too, but this does not seem to be happening in many regions.

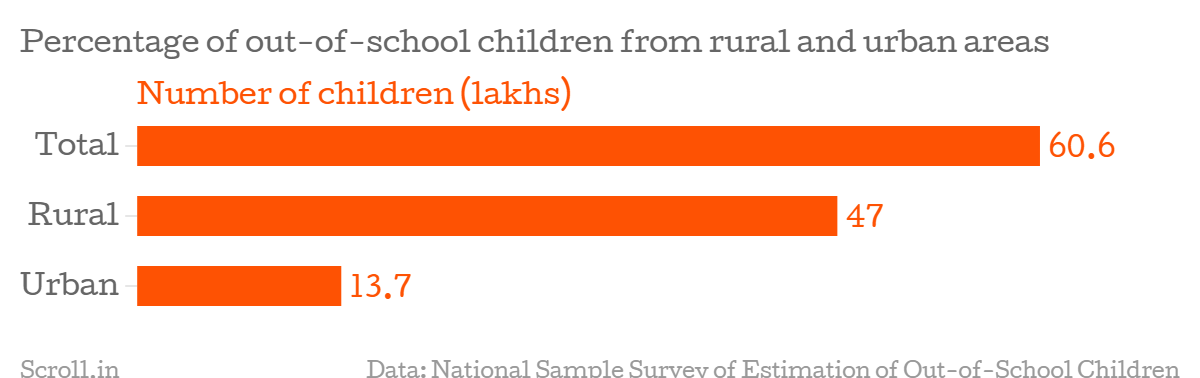

One such divide is the urban-rural background of those who are out of school. In crude numbers, more than 47 lakh children out of school belong to rural areas while only 13 lakh come from urban neighbourhoods.

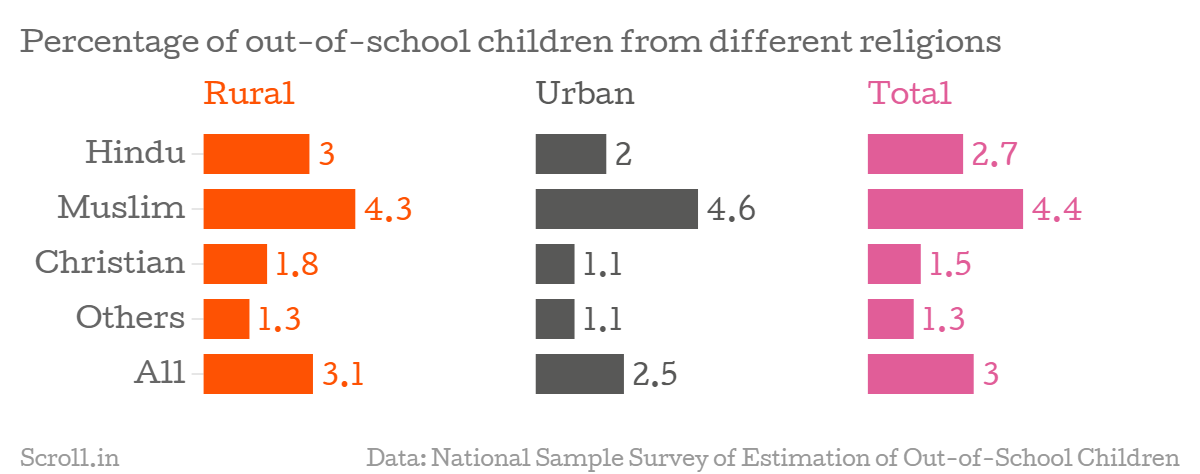

What this means, is that even as enrolment is increasing, the disparities are not fading away. Looking at the proportion, this inequality becomes even clearer. In rural areas 3.13% of all children are out of school while in urban regions it is only 2.54%, thus making it clear that accessibility is still an issue in the interiors of the country.

Shunning the disadvantaged

More worrying is the fact that those belonging to the marginalised communities are still out of schools for various reasons as academics feel that the government is not doing its part to ensure inclusivity in education.

Over 32% of those out of schools are Dalits and over 16% belong to the Adivasi communities. On further bifurcation, 3.24% of all Scheduled Castes and over 4% of all Scheduled Tribes children are out of school nationwide. This divide gets even bigger in the eastern region where more than 6.78% of ST children are out of school and in Odisha the figure is a whopping 14.81%.

“The discrimination could be happening in the classrooms as well, that can’t be denied,” said Kiran Bhatty, a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy and Research who has worked as an education expert on several projects, including with the government of India.

Bhatty feels that if the existing forms of sensitisation training are not proving effective then it might be time to explore other ways the same can be inculcated in teachers who spend the most time with students in schools. “Maybe we need to remodel the whole programme and focus on training teachers in a way that their outlook towards these communities changes,” she added. But, the government had reduced the mandatory teacher training duration from 21 days per year of service to just seven days per year, Bhatty informed.

Muslims out of school

Similar is the case for religious minorities such as Muslims. An on-ground study by the organisation Human Rights Watch last year uncovered many instances of Hindu teachers making denigrating remarks about Muslim students in the classroom. The report highlighted multiple stories of children in areas such as Delhi being discriminated against on the basis of their religion and not being allowed to participate in sports and other class activities.

According to the Social and Rural Research Institute report, 4.43% of Muslim children were found to be out of school, significantly higher than the national average of 2.97% across religions. Interestingly, Delhi leads the pack when it comes to the divide in education access as 15.76% of Muslim children in the city are out of school.

Bhatty feels that the enforcement of RTE leaves much to be desired and these communities vulnerable. “There is a judicial recourse against such discrimination and maybe someone needs to go to the court,” she said, but added that it might not even be an option for the families who find it too hard to afford education. “Our judicial system takes years and months to solve cases and what will children do in the interim?” she asked.

“The RTE implementation has been sketchy from the beginning and lack of accountability makes it tougher to enforce,” Bhatty said. “There should be grievance addressal mechanism and some helplines where complaints are heard and can be addressed, but the problem is that RTE is still treated as a scheme and not a law,” she concluded.