This relaxation of visa policies is being championed as a promising way to draw tourists to India, but how much of a role has it played in driving tourism so far? Almost negligible, according to a new research paper studying India’s visa-on-arrival statistics.

In a paper titled “Atithi Devo Bhava?” published in the Observer Research Foundation’s Issue Brief last month, researchers Natasha Agarwal and Magnus Lodefalk observe a curious trend: the number of tourists availing of visas on arrival has grown on average by 60% since the scheme was first introduced in 2010, but they still comprise less than half a percent of the total tourists visiting India.

The reasons for this disparity, the authors suspect, could be as simple as lack of clarity about visa conditions on Indian websites to the initial choice of countries with little trade interest in India.

Disparate numbers

In January 2010, the central government introduced the Tourist Visa on Arrival scheme for five countries – Singapore, Japan, New Zealand, Finland and Luxembourg. Over the next three years, the policy was extended to six more countries, including South Korea, Indonesia and Myanmar. The real expansion came under the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government in November 2014, when the ministry of tourism added 32 countries to the list, including the United States, Australia, Germany, Israel, Russia and United Arab Emirates.

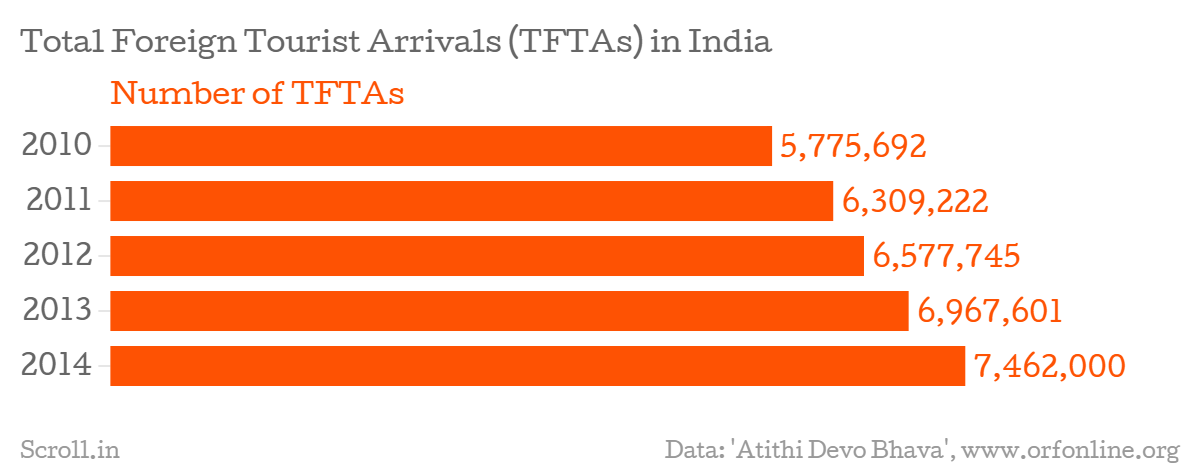

During this four-year period, tourism to India grew at an average annual rate of 9.2%, from 5.8 million incoming tourists in 2010 to 7.5 million by the end of 2014.

The number of TVoAs issued to travellers also saw a significant growth, from 6,549 tourists availing of the scheme in 2010 to 39,046 tourists in 2014.

Despite these encouraging figures, the number of tourists using the visa on arrival scheme to visit India has never formed even one percent of total foreign tourist arrivals: from 2010 to 2014, TVoA users comprised an average of just 0.27% of all tourist arrivals in the country.

From visas on arrival to e-visas

At the end of November 2014, the central government attempted to reform the visa on arrival scheme by introducing Electronic Travel Authorisation for all the 44 countries eligible for TVoAs.

ETA meant that tourists had to apply for a visa online a few days in advance and carry a copy of that visa with them when they travel to India. (Since this is not technically the same concept as “visa on arrival”, the government finally changed the name of the scheme to e-tourist visa in April 2015).

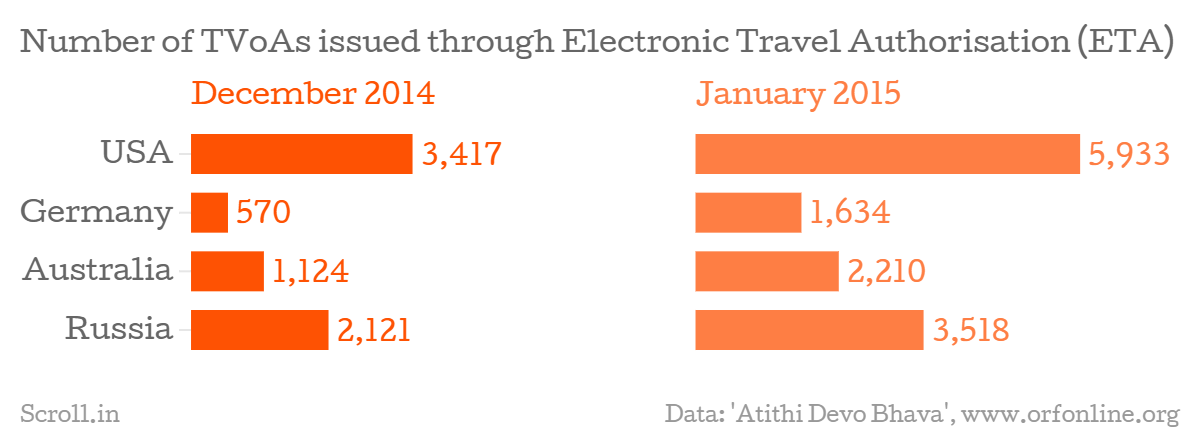

The change in policy did draw more takers among tourists, particularly from countries like the US and Russia.

Since November 2014, India has granted the e-tourist visa scheme to 33 more countries, largely from Central America, South America and eastern Europe but also France, Canada and now China.

But Agarwal and Lodefalk believe the ambitious expansion may not prove to be the game changer for Indian tourism unless the government pays attention to why it hasn’t been very successful so far.

The flaws

Among the countries eligible for visas on arrival/e-visas, most tourists have not shown much inclination for the new scheme. Singaporean tourists, for instance, have shown a clear preference for obtaining traditional visas to India, even though Singapore was one of the first five countries to be granted the TVoA scheme.

“Although the growth rate of TVoAs issued to Singaporeans has increased from 2% in 2011 to 65% by 2013, the average share of Singaporeans that obtained TVoA over the period 2010-2013 is less than 2% of the total arrivals of Singaporeans in India,” Agarwal and Lodefalk point out in their analysis.

One of the main reasons, they believe, is poor implementation of the scheme. India’s official tourism website, for instance, does not clearly define the objective of the scheme, the paper points out. The scheme is applicable to travellers with the objective of visiting India for “recreation, sightseeing, casual visit to meet friends or relatives, short duration medical treatment or casual business visit”. The details of what qualifies as “short duration medical treatment” or “casual business visit”, however, remain undefined.

Agarwal and Lodefalk compare this with visa eligibility instructions for travellers to Australia, where the nature of these categories is explained in detail.

Other problems include technical difficulties that travellers to India have blogged about – problems with uploading photos or making payments smoothly.

Choice of countries

So far, the paper points out, the success of the visa on arrival scheme has also suffered because of the kind of countries it has been extended to. The majority of the first 44 eligible countries studied by Agarwal and Lodefalk have traditionally not been major source countries for tourists to India.

E-visas can only be applied for online, and a large number of the 44 eligible countries have limited access to the Internet. In countries like Kenya, Cambodia, Thailand and Indonesia, for instance, less than 30% of their populations use the Internet.

Finally, India has very limited trade relations with the majority of the 44 countries it has granted the e-visa scheme to, a factor that also restricts interest in tourism. “The government could focus on extending the TVoA scheme to countries of economic significance,” the authors point out.

In that light, Modi’s recent decision to “look east” and grant e-visas to China is perhaps a good starting point.