That’s what everyone says when supporting the abolition of the death penalty, right? But, to apply Wikipedia’s standards to this debate, where’s the citation? Is there really no correlation between the death penalty and a reduction in crime?

First, let’s sharpen the query. The question isn’t whether the death penalty provides a deterrent effect. The question is, “Does the death penalty provide a deterrent effect that is greater than that of long-term incarceration”. If not, then it’s obvious that the death penalty is redundant from the point of view of deterrence.

American lesson

The United States has had a long history of debate on the death penalty and it’s instructive to look at some studies there.

The first thing researchers would look for is a correlation between homicide rates and the death penalty. If the death penalty had a significant deterrent effect compared to other methods of punishment, such as long-term incarceration, then it should come up in the data. Think of, say, higher rates of obesity among soft drink consumers or higher rates of cancer in smokers as an equivalent study.

Researcher Thorsten Sellin took American crime data from 1920 to 1958 and ran a comparison between US states which had the death penalty and neighbouring states which had abolished it.

Sellin found no apparent correlation in the rate of homicides with the existence of a death penalty. Neighbouring states had similar crime patterns, unaffected by whether they were willing to hang people or not.

Moreover, when states removed the death penalty, they didn’t see more murders. In fact, when North Carolina stopped executing people in 2006, it saw a fall in its murder rate.

Brutalisation effect

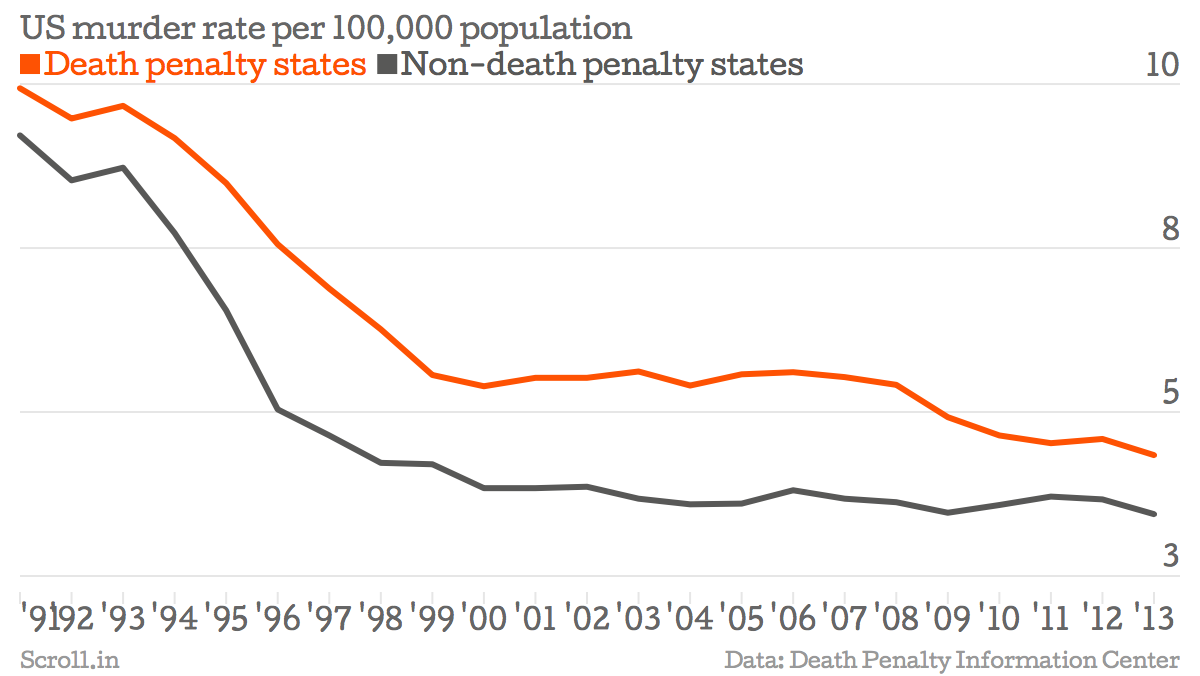

This effect holds even today. In fact, at present, US states without a death penalty have lower rates of murder than states with a death penalty.

This increase in murder rates with the death penalty – the “brutalisation effect”, as it’s called, is actually not that uncommon. California, as it so happens, had higher rates of murder between 1952 and 1967, when it was executing people, as compared to 1968-’91 when it wasn’t. In a study conducted by Bower and Pierce, it was found that between 1907 and 1963 in New York, murder rates increased on an average in the month following an execution.

While all of this is compelling data, it must be noted that none of these completely rule out the deterrent effect of executions. They just prove that it’s not very large, at best. The issue here is that researchers are hamstrung by the fact that they can only conduct a very limited number of empirical experiments, since of course, you can’t, say, execute people on a whim to test your hypothesis.

Grey area

In fact, in 1976, a study by economist Isaac Ehrlich showed a slight negative relationship, between the murder rate and the execution rate. This created quite a stir in the US, since much of the public mood there, quite like in India, is rather in favour of the death penalty.

Unfortunately, Ehrlich’s study didn’t hold up too well to scrutiny. John Lamperti, Professor of Mathematics, Dartmouth College, writes that “indication of deterrence was extremely unstable when small changes were made in Ehrlich’s assumptions”.

“The earlier conclusion, that US murder statistics give no evidence for a unique deterrent effect of capital punishment, still stands,” summarised Lamperti.

As noted above, given the limitations of the type of experiments researchers can conduct, they can never be 100% sure that there is no deterrent effect of capital punishment. Or, for that matter, be 100% sure that there is one. As John Lamperti noted, an ideal experiment would be along the lines of the Salk vaccine trial, where almost a million children were involved, some being administered the real vaccine and others a placebo. Of course, nothing like that can be carried out for the death penalty for obvious moral reasons. We can’t put people to death to conduct an experiment.

Consensus on its redundancy

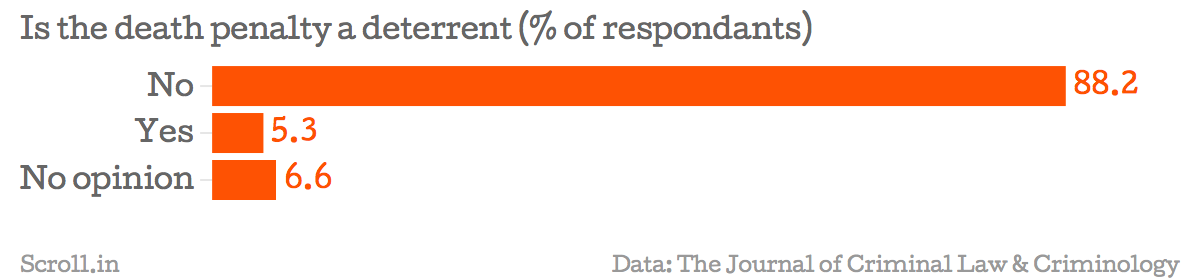

Nevertheless, we can be quite sure that even if there is a deterrent effect, it is small. And most of the people who matter think it is either nonexistent or is small enough to be ignored for all practical purposes. In other words, there is a consensus on the redundancy of the death penalty in deterring crime.

In a 2009 survey, Professor Michael Radelet and Traci Lacock of the University of Colorado found that an overwhelming majority of top US criminologists didn’t think the death penalty had any special deterrent effect on murder rates.

This result is backed by a survey of police chiefs in the US too, for whom more usage of the death penalty is an area of least concern. “I have seen the ugliness of murder up close and personal,” said Gregory Ruff, a US police officer for 23 years. “But I have never heard a murder suspect say they thought about the death penalty as a consequence of their actions prior to committing their crimes.”

The company India keeps

Given this overwhelming consensus on its lack of effectiveness, countries as a whole are moving away from the death penalty. The UK abolished it in 1973, Canada in 1976, France in 1981, Australia in 1985, Italy in 1994, Spain and South Africa in 1995. The United States is the outlier here in the developed world since it still retains death penalty (not only in this case, in the First World the US is a conservative leader). As the Economist puts it, “America is unusual among rich countries in that it still executes people”, but support for the move is falling and it’s only a matter of time before it does away with it too. At the state level, already 38% of US states have abolished the death penalty.

Meanwhile, India is in depressing company when it comes to allowing death sentences. Some of the other prominent countries which allow state-sanctioned murder as a means of justice are China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, North Korea and, fittingly, our subcontinental twin, Pakistan.