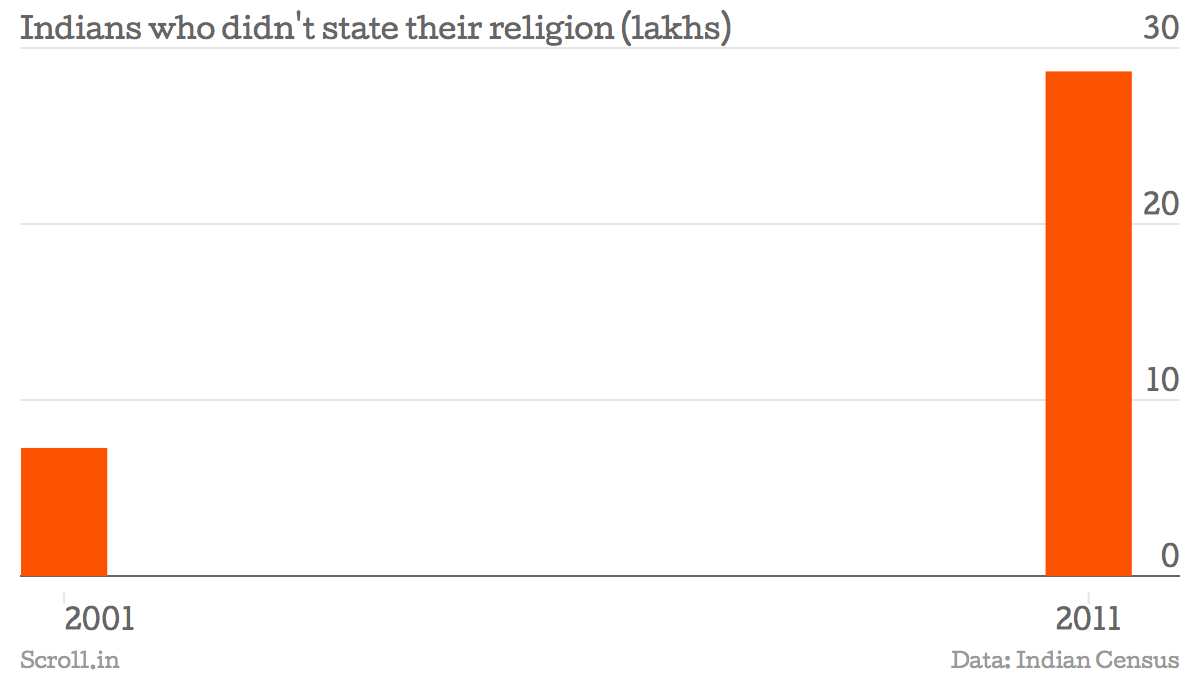

Around 29 lakh people in India fall into the “religion not stated” category in the Census 2011 results. This comes to only about 0.24% of India’s population, but it does represent a significant jump from a decade back. In the 2001 Census, government enumerators had recorded only 7 lakh people under the “religion not stated” category. So, rather than any religion being the fastest growing category, it is perhaps the atheists who have grown the most – increasing four times over the decade, at an average annual rate of 15%.

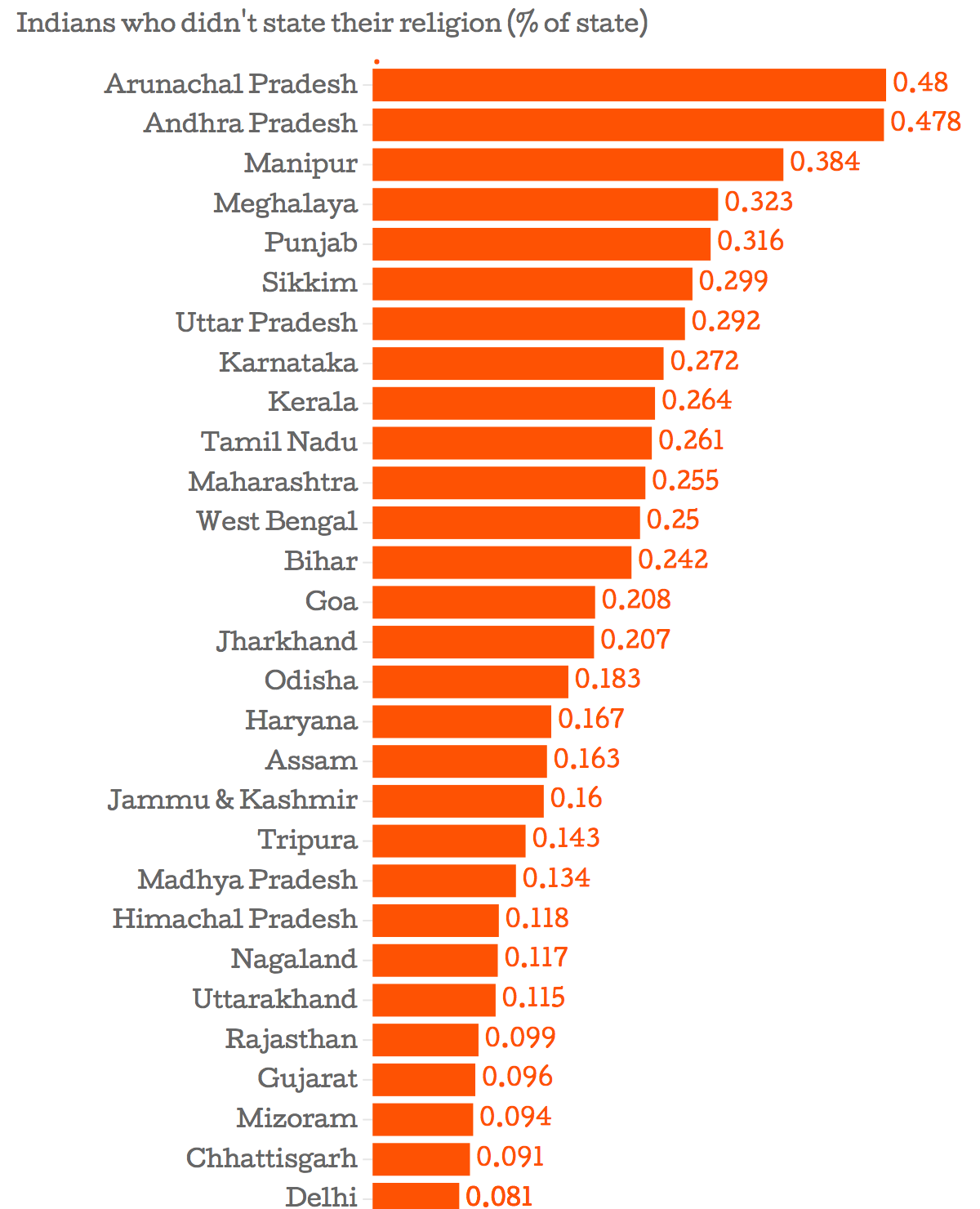

Looking at state-wise statistics is quite instructive. The two APs – Arunachal Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh – come out on top with close to 0.5% people choosing to not state their religion.

Delhi, the only city-state on the list, comes in last with only 13,606 choosing not to state their religion. Given the large number of upper class Delhiites who choose “atheist” for their social media profiles, this comes as a bit of an anticlimax. There are other incongruencies too. The number of people who did not state their religion in the communist strongholds of West Bengal and Kerala is only 2.3 lakh and 88,000 respectively. With more than 7 lakh Communist Party of India (Marxist) members in West Bengal and almost 3 lakh in Kerala, not to mention the many communist sympathisers, the Census figures do not triangulate.

All of this goes to show that the “religion not stated” category is actually a poor fit if one would want to approximate it to “atheist/agnostic”. It also shows how what we pass off as religious categories in India – Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian – are actually better thought of as ethnic categories, based more on birth than actual belief.

No country for atheists

This is in fact, something that the Indian state has stated quite explicitly. In 2012, Shrirang Balwant Khambete, a practicing advocate, petitioned the Thane session court to be declared non-religious. It seemed like a simple enough request, since he claimed he was an atheist. The court, however, didn’t agree with him. Given that India functions under a system of religious personal law, Khambete being declared a non-Hindu would have put him into legal limbo. While there are personal laws for Hindus and Muslims, there is no such thing for atheists. Due to this legal lacuna, the court declared that Khambete could believe what he liked personally, but legally he would have to remain “Hindu”.

Indian atheism, though, is struggling to break out of the legal binder. While strains of atheists thought are very old in India – for instance, Buddhism is silent on the question of a god – rationalist, post-Enlightenment atheism saw its entry in the colonial age. Much of this was concentrated in what was then Madras Presidency, with Periyar’s militant rationalism acting as the vanguard.

This strain of Indian rationalism saw a great amount of success with Dravidian and Communist parties coming to power in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, respectively. The past three decades, though, have seen a pushback, as the Hindutva movement gains strength. Unlike Islam or Christianity, Hinduism has no scriptural beef with atheism per se. Hindutva’s rhetoric, though, seeks to change that, attacking rationalists whose beliefs are now thought to blaspheme Hinduism.

Hindutva backlash

Perumal Murugan, a Tamil writer, announced his “death” as a writer in April, after local Hindutva groups threatened him and his family harm for attacking Hindu religious practices. Other deaths were more literal. In 2013, anti-superstition activist Narendra Dabholkar was killed in his hometown of Pune. In 2015, another Maharashtrian rationalist, Govind Pansare, was murdered in much the same way.

Most recently, Kannada scholar and rationalist, MM Kalburgi, was murdered again in the same way as Pansare and Dhabolkar – shot by as-yet unidentified assailants. Kalburgi, like Pansare and Dhabolkar, had a long history of run-ins with Hindutva groups. In June 2014, in fact, protesters from the Bharatiya Janata Party even held a mock funeral for him, according to NDTV.

After Kalburgi’s murder, a Bajrang Dal activist, Bhuvith Shetty, even threatened another rationalist, KS Bhagwan. In keeping with the Indian state’s soft approach to such matters, however, he was soon released out on bail, signifying the dire straits Indian rationalism is in now – irrespective of the impression the Census figures give.