The document titled "India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution: Working Towards Climate Justice" declares that the response of developed countries has been “tepid and inadequate” resulting in an “emission ambition gap”.

India’s contribution, or INDC as it is called officially, to bridge that gap has three quantifiable targets – reduce the emissions intensity of its gross domestic product by 32-35% by 2030 from 2005 levels, to draw 40% of its electricity from non-fossil fuel energy sources by 2030, and to create a carbon sink that has a carbon dioxide equivalent of 2.5-3 billion tonnes through afforestation.

India has refrained from committing to a cut in absolute emissions even though the US, the EU, China and Brazil have all done so and has maintained its development prerogative.

"This is a clarion call for climate justice for both poor countries and poor people," said environment minister Prakash Javadekar, addressing the press at the release of the document. "We are not part of the problem but we want to be part of the solution."

The INDCs are positive and aggressive, according to Harjeet Singh who is the climate policy manager for ActionAid International. “The international community can keep saying that India should do more but we have much to catch up on development in terms of electricity supply, etc,” he said. India is the third biggest carbon polluter but stands at a low 135 out of 187 countries on the Human Development Index.

Between the lines

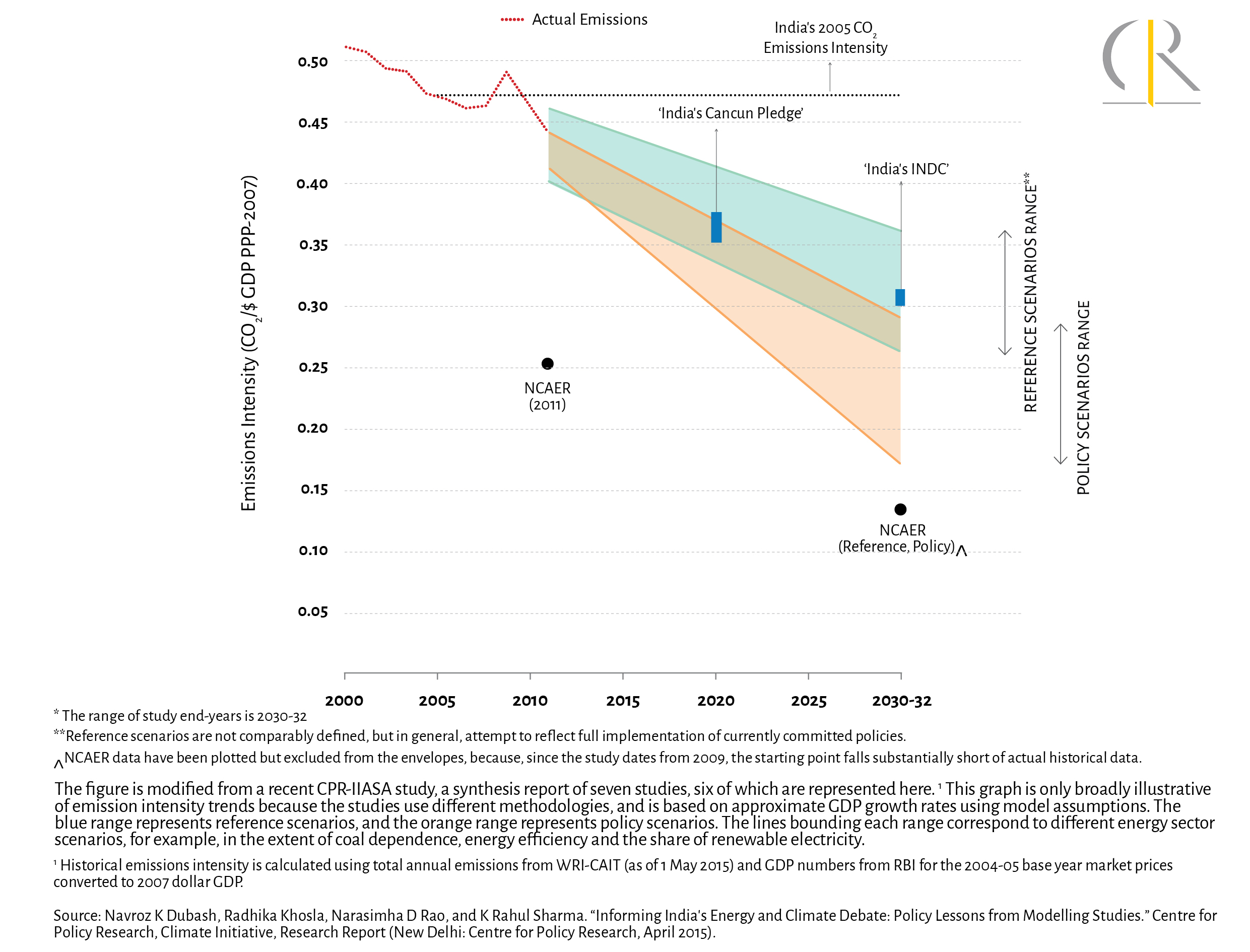

India’s INDC declaration has few surprises. In earlier commitments, India had undertaken to reduce its emissions intensity by 25% by 2020 from 2005 levels and has already achieved a 17% cut. Meeting a goal of 35% is entirely doable and previous studies have shown that India can reduce its emission intensity by up to 40%.

“The emissions intensity target is conservative when benchmarked against past studies which suggests that the real action is in the sectoral numbers,” said Navroz Dubash of the Centre of Policy Research. The INDC statement includes a list of new initiatives and priority areas like thermal power generation, transport, buildings, appliances and waste management, which is important as a sign of key economic and infrastructure ministries being engaged in formulating climate policies.

India might also be keeping its best emission intensity reduction target, one higher than 35%, as an ace up its sleeve, a card to play during the negotiations in Paris.

Figure: Centre for Policy Research

There's another argument for why the emissions intensity target might be only 35% and that involves the much publicized Make In India scheme. An emissions intensity reduction of 35% can only be achieved if the share of manufacturing in the economy doesn't rise significantly, finds T Jayaraman, professor at the School of Habitat Studies at Mumbai's Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

"In recent times, trends suggest that there is some saturation of manufacturing efficiency in some sectors, which means with more manufacturing growth there will be more emissions. If you have plans for Make In India which are serious and by which manufacturing needs to grow, then this level of achievement will get tight," he said.

The Narendra Modi government has, for the past year, been promoting an ambitious scheme of having a renewable energy capacity of 175 gigawatts of renewable energy installed by 2022, which is a quadrupling of current capacity. In committing to a 40% from non-fossil fuel sources the government says it will increase the space of alternative fuels in the energy mix even though “coal will continue to dominate power generation in future.”

“The 2030 fossil fuel-free energy number, whether bold or not, will depend on whether we meet the renewable energy 2022 number of 175 GW,” Dubash said. “If we meet 175 GW then we will easily meet the 40% number and exceed it. If we don’t meet 175 then we may just about get to the 40% number by 2030. What it implies for renewable energy depends on what we do with nuclear energy.”

The INDC document sets out a nuclear energy capacity target of 63 GW installed capacity by the year 2032, which Dubash feels is unlikely to be met.

The Indian government has chalked up an ambitious blueprint for a carbon sink plan but has been making far from reassuring moves on afforestation. Earlier this month, the environment ministry issued guidelines to hand degraded forests over to the private sector to grow timber and other forests produce. The degraded forests comprise 40% of India’s forestland and the proposal has several problems, not the least of which is the possible conversion of natural forests into hectares monoculture plantations that will result in loss of habitat and biodiversity.

Stress on climate justice

The INDC document also reiterates Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for climate justice at the United Nations summit to adopt the Sustainable Development Goals last week. “The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities is the bedrock of our collective enterprise,” Modi said.

The government estimates that India will need to spend $206 billion between 2015 and 2030 on climate adaptation measures for agriculture, forestry, fisheries, water resources and ecosystems. Adaptation in the energy sector could cost more than $7 billion, the document says citing figures from the Asian Development Bank. On the flip-side, India’s annual economic cost from climate change could run up to 1.8% of it gross domestic product by 2050.

Furthermore, according to preliminary calculations India will need $2.5 trillion to carry out its intended climate actions up to 2030, the document states.

Tirthankar Mandal, senior advisor at New Delhi climate consultancy Climate and Development Advice, feels that the Indian government, while asking for developed countries to pay up, isn’t expecting much by way of international climate finance. Simply putting forth a bill in trillions of dollars is a signal that it might rely on domestic resources and the private sector and not underfunded international mechanisms. The Green Climate Fund, for example, is supposed to have a corpus of $100 billion by 2020 but less than a tenth has been committed to it, and that too only in the form of pledges and not actual money.

On the other hand, India is in aggressive pursuit of technology. “The Smart Cities scheme and renewable energy scheme that figure very prominently in the INDCs cannot be carried out without technology transfer,” said Mandal. “Even in the recent visit of Modi to Silicon Valley, he has been talking about investment in terms of technology and not just stock market investment.”

Negotiating Climate Action

The INDCs from India and other countries will form the basis of the all-important climate conference in Paris later this year. The Conference of Parties has been set the gargantuan task of developing a concrete global plan to restrict global warming to at least 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The outlook for such a plan is rather bleak at the moment. On October 1, the deadline for the INDCs, Climate Action Tracker released an analysis saying that the combination of declared government actions was only enough to restrict warming to 2.7 degree Celsius.

In New York last week, 193 member states of the United Nations adopted the Sustainable Development Goals that widely recognised the impacts of climate change and the need to integrate climate action into policies to reduce poverty, hunger, and inequality. The SDG document, while acknowledging the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change as the primary body that decides on international climate negotiations, sends a signal for strong action.

“The final SDG document has both the 2 degree Celsius and 1.5 degree Celsius scenarios,” Singh of ActionAid pointed out. The 2 degree Celsius target was a product of the failed Copenhagen summit on climate change in 2009. Since then, scientific studies have shown that, even a 2 degree Celsius warming will result in disastrous losses of life and territory.

“Two degree Celsius is a more political target and 1.5 degree celsius reflects a much better understanding of science,” Singh said.

All eyes are now on the Paris meeting at the end of November. “It is going to be an interesting dynamics that will unfold [at Paris]. Most countries are putting out their second-best ambitions now. Most countries will put out higher INDCs if required at the last minute,” said Mandal.