In 2008, less than 400 students appearing in their Class XII examinations conducted by the Central Board of Secondary Education scored more than 95% marks. In just six years, the number of such students jumped by a whopping 23 times as close to 9,000 students scored near perfect scores in the year 2014, according to a report in the Indian Express.

This is the result of the “moderation” policy being followed by schools across the country, not just those affiliated to the CBSE. While schools are increasingly giving liberal marks to students in the board examinations, presumably in order to reduce instances of stress and depression, this hasn’t really helped.

Now, the moderation policy is set to find a place on the agenda of a national level meeting of state boards called by the HRD Ministry in order to discuss ways to counter this problem, among other things. The moderation policy which is often used to “bring uniformity in the evaluation process” is admittedly leading to disappointed students who face “unrealistically high” cut-offs when they seek admission in premier colleges.

Even though the ministry might end up telling the boards to not be so liberal with marking anymore, academics say that the problem of inflated marks runs much deeper.

“What we are seeing is a huge crowd of students with sky-high marks waiting to grab a seat in the limited capacity available in premier institutions,” said a sociology professor in Delhi University. “Even if we have lower average scores, it doesn’t mean that the competition will reduce as long as the seats in good institutions aren’t increased and new institutions aren’t brought in to accommodate the influx.”

About 1.5 crore students take the class XII exams every year across the country while Delhi University, which is one of the largest universities in the country, has only 54,000 seats on offer across its 70 colleges.

Devaluation of education

While more students scoring high marks should be seen as a good thing, it is becoming a problem of enormous measure for the colleges to keep their cut-offs low and in some cases, the trend of high scores just continues throughout the university education as well.

“The government should take a look at private institutes to learn why nobody goes there,” said Abha Dev Habib, professor of physics at Delhi University and a member of the Delhi University Teachers Association. “Students want value for money and they flock to public universities because the government funds them and the degrees hold some value," she added. "But with inflated marks, that value is fast eroding.”

Many teachers in Delhi University cite anecdotal evidence of more and more students scoring above 80% marks while the toppers often secure aggregate scores anywhere between 90 - 99% even at the university level. The problem, academics claim, lies in the fact that academic scores spell the end-all of a student’s life instead of his learning or potential.

“Everyone from the teachers to the college to the university as a whole are incentivised to give more marks so that they can do better on rankings and obtain better grants and funding,” an Associate Professor from an off-campus Delhi University college said. “Even if one university doesn’t give liberal marks, others will and soon it will lose out on funding and rankings. There’s a chicken and egg story here.”

Race to the top

Habib agreed and described how Delhi University itself has been known to inflate marks of students to make sure its public perception doesn’t get affected even after experiments such as the Four Year Undergraduate Programme which was rolled back after much back and forth.

“One reason behind awarding marks liberally is that it keeps dissent in check,” Habib said. “Students don’t revolt because they feel they are doing well and the general public thinks that the system must be working and that’s why students are scoring good marks. However, they are all being misled.”

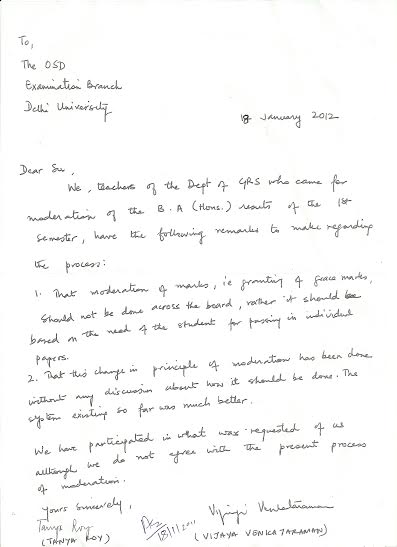

This was also highlighted in a dissent note submitted by a section of Delhi University teachers to university officials in 2012, when the semester system first came into effect, to protest against the blatant inflation of marks which led to a large number of students getting unrealistically high scores in their papers. Incidentally, the data collected by teachers for multiple courses in the university showed that full-marks was actually the most common result, in many subjects. This implies that more students were scoring 75 out of 75 in their papers than any other score because a certain bump, say, of 5 marks was added to everyone's score.

"Hence, those scoring 70, 71, 72, 73 were automatically upgraded to 75 marks and it means that the university is trying to hide its failures," the report said, a copy of which is with Scroll.

Many Delhi University teachers claim that even though they rigorously mark students on internal assessments, a bump of 10-20% is usually provided to everyone in the external examinations which leads to students forming a rosier picture in their head about their academic prowess.

“Those who go out to work after getting 95% marks on a Delhi University degree are likely to be shocked and disappointed at how little they know,” she said. “The system is making them believe that they are competitive without thoroughly testing their learnings or even their desire to pursue a certain discipline. Getting more than 90% in Delhi University is no big deal anymore.”

While critics claim that entrance examinations are an alternative to the over-dependence on marks, there are fears that it will put more pressure on students and result in the mushrooming of coaching-centres economy.

“There’s no one way to solve this,” Habib said. “The government should first realise that its own policies are hurting the education system and quick-fixes won’t do because they can plug one leak but something else will break down soon and we’ll be having the same conversation again,” she added.