For many, the victory it is only a partial one, a short-term solution deferring the problem to another day. It does not resolve the issue of unaffordable education nor does it address other important issues that the national action has been tied to like the outsourcing of labour on university campuses or the general discontents of the lack of transformation at higher education institutions in South Africa.

Students march to the airport in Cape Town. Courtesy Barry Christianson.

Seven major universities shut down on October 21, with more joining the #nationalshutdown soon after. Massive proposed fee increases of up to 11.5% for 2016, a price hike that would be unaffordable for most students around the country, called into question the liberatory, and now long forgotten, promises made by African National Congress that education would be free, or at the very least affordable, after apartheid.

What began as a sit-in and protest against proposed fee hikes at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, soon led to a complete halt of activities on campus when students called their Vice-Chancellor to a mass meeting. As we witnessed after the Marikana massacre of striking mineworkers in 2012, the protests spread like wildfire across the country culminating in a #nationalshutdown.

Students in Port Elizabeth, Grahamstown, East London, Johannesburg, Limpopo, and Cape Town have been met with extremely disproportionate violence from police. The South African police, who have become infamous for their trigger-happy, outrageously, destructive behaviour, and sinister smiling faces whether they are killing striking miners, tearing down the homes of people occupying empty land or firing stun grenades and tear gas at university students, were not deterred by the outrage on social media or the protests and rational arguments from students and academics.

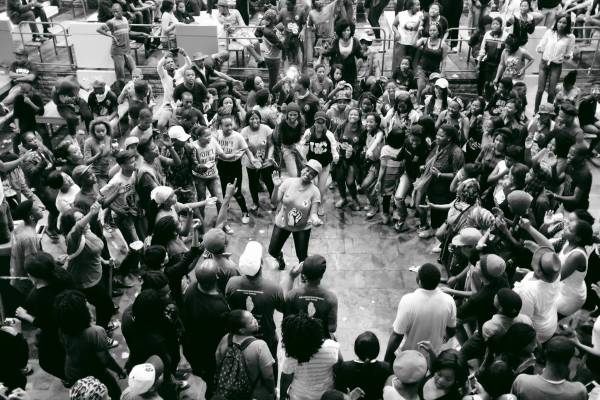

Students at University of the Western Cape. Courtesy Musaed Abrahams.

Meanwhile on the morning of Wednesday, October 21, in the Parliament of the usually quite serene streets of Cape Town, doors were tied together with cables and couches were pushed against them as the officials inside became increasingly worried about the young, protesting electorate outside. The students of the University of Cape Town joined by workers and other supporters had marched to parliament to demand to see Blade Nzimande, the National Minister of Higher Education. The fear of the politicians inside, growing by the minute, convinced them of the need for heavily armed police officers.

Outside Parliament. Courtesy Mirriam Moate Mathebula.

A worried Blade Nzimande, whose name has inspired all kinds of creative and especially humourous placards about fee increases and the apparent bluntness of his approach, emerged a few hours later, but failed to get the thousands of students, chanting “#blademustfall” to ‘cut-it-out’ when he tried to address them. Instead they threw water bottles at him, and between another favoured South African expression of dissatisfaction, they booed and told him they were tired of waiting for his programmes and planning committees and that the #feesmustfall now.

Hashtags, by the way, have become so dangerous in South Africa, that in possibly another first in South African legal history, the management of the University of Cape Town were successful in attaining a court interdict citing #feesmustfall as a second respondent, effectively suing a hashtag.

The protestors, some of whom had convinced some of the university bus-drivers to take them to Parliament shortly before the University of Cape Town reported the buses stolen, continued to arrive in their thousands outside the building. Exercising their democratic rights, they decided to enter the gates and within minutes, police began firing stun grenades, tear gas, and rubber bullets into the crowd of students. In what quickly began to resemble a scene out of 1976 Soweto Uprisings during apartheid South Africa, 29 students were arrested and six of them were charged with high treason.

The police followed fleeing students around the city of Cape Town for half an hour after they had dispersed, after they had dragged 23 others with a use of force reminiscent of American policing of black youth, and threw them into the waiting police vans. In Grahamstown, the police arrived with an ambulance before the protest had begun. Perhaps the students paused for a quick sigh of relief; in the case of Marikana, they had been ready with mortuary vans.

When students stormed Parliament’s grounds on Wednesday afternoon, Shaun Swingler was there to document the police’s brutal response.

The South African government has left no doubt that its unofficial policy on tackling any kind of popular mass action is violence. Soon after students had run in fear and horror from their own police force in Cape Town, the ANC’s official Twitter account commended police for dealing with the “hooliganism” outside Parliament, echoing the congratulatory address former Chief of Police Riah Phiyega to police officers after they had gunned down 34 mineworkers in Marikana in 2012.

The framing of students as hooligans, and as violent or irrational protestors, has not been limited to the ruling party. The mainstream bourgeois liberal media has taken up this trope with fervour. Rather than reporting on what is a historic moment for struggles against the corporatisation and neo-liberalisation of the university, it has chosen instead to focus on the damage caused to property, the so-called forced entry of students into public spaces, or the disruption of class and potentially, exams. African universities have long been under attack through both the neoliberalising forces of structural adjustment policies or through the general trend of corporatisation that students in Chile, Berkley, Quebec, have fought, and won, against.

The #feemustfall movement, however, must be considered as part of a longer and deeper struggle when South Africa’s midnight’s children awoke with a start in the early months of this year.

What led up to the #feemustfall movement

At WITS University in Johannesburg, in the last months of 2014, a group of Politics students released a document titled, “Transformation Memorandum 2014”. In it, they outlined several of their frustrations with the lack of transformation within their department, but also within the university as a whole. Calling WITS a microcosm of South Africa, they said they were alarmed by the slow progress of transformation in reference to the composition of academic staff, particularly the lack of black academic staff members especially women. The South African academy remains dominated by white academic staff; currently only 14% of professors are black, while the University of Cape Town does not have a single black female professor. The WITS students also targeted the untransformed curriculum that did not reflect their lived experiences as black students, or that the university was part of the African continent.

While the transformation memo did create some waves within academic circles, it wasn’t until March 2015, when a group of students at the University of Cape Town threw buckets of feces on a statue of Cecil John Rhodes on the campus, that the lack of transformation at higher education institutes started making headlines. Almost immediately, the Rhodes Must Fall movement was born, calling for the fall of the statue and the beginning of a conversation to decolonize the university. The movement, which drew thousands of students from the University of Cape Town campuses, to its meetings, started occupying the Bremner building on the campus renaming it Azania House, the name used by Black Consciousness anti-apartheid freedom fighters to refer to South Africa.

Over the next few weeks, the Rhodes Must Fall collective held a series of protests on campus, posters, performance art, and demonstrations, in the month between 9 March and the removal of the statue on 9 April, Azania house functioned as headquarters for all radical activity on the UCT campus. Rhodes Must Fall linked their campaign to the struggle for black liberation in a colonial space, not merely for the students but also for the black academic staff and the black workers and support staff on the campus. They used Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko, to define the theoretical foundations of their movement. Biko founded the Black Consciousness Movement in 1969 during his time as a medical student at the University of Natal and one of his expressions, “Black man you are own your own” became a rallying cry for students and activists alike and highly influenced the student protests of 1976. In addition, midnight’s children or “born-frees” as they are called in South Africa, added a new and strong feminist dimension to the black liberation philosophy giving way to a new rallying hashtag: #patriarchymustfall.

Movement spreads

Within a few days on March 17, students at Rhodes University met outside the university administration buildings on a very cold and rainy Grahamstown day, in order to show solidarity with the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town. Students then began discussing the slow pace of transformation at Rhodes University and their own pain and frustrations as black students within a neo-colonial institution. The Black Students Movement was formally constituted on that day and began calling for the name of Rhodes University to change. Shortly after joining the revolutionary spirit of the Rhodes Must Fall movement, the Black Students Movement began organising on campus by reaching out to black students and staff and occupying the Senate room, renaming it the BSM Commons.

Only a few days later, a group called Open Stellenbosch released a statement on their facebook page, following a demonstration at the historically white Afrikaaner University, titled, “Who belongs here.” The group of predominantly black students felt as if they were unwelcome at the university that persisted in using Afrikaans as the medium of instruction for classes. They defined themselves according to the tradition of Biko’s black consciousness and as such in their use of black students, they stressed, was that black be a political category rather than one tied to pigmentation.

The TransformWITS movement joined soon after, calling for similar changes to the institutional culture of the university. Its manifesto, defined the students’ initiative as a non-partisan movement within the Bikoist tradition with an intersectional approach that rejects liberal notions of respectability politics when it comes to student practices and protests. The rejection of respectability politics was something that not only profoundly linked these movements to Biko’s critique of white liberals and their elite inter-racial tea parties in the suburbs, but also to the students’ frustration with black members of management who were considered to be acting against, rather than for, genuine decolonisation and transformation.

The students, who have from the beginning displayed an incredible discipline, calm and intellectual sophistication were, then too, described in the mainstream media as violent, irrational, hooligans. The charge came not only from racist quarters, but, perhaps in hindsight not so unsurprisingly, from struggle veterans and former anti-apartheid student leaders themselves, who told them to be quiet, study hard and stop complaining because they did not know what real struggle was about.

The students, in the face of growing resistance and hostility from university management, who had as early as April began to routinely call police on protesting or occupying students, remained defiant continuing in their respective institutions to call for decolonisation of the university in all its structures. Within this, they included the neo-liberal practice of outsourcing labour instituted at UCT as early as 1997. For them, they could not be free without also recognising the oppression of those around them who were, for many, not so different from their mothers, brothers, fathers, and sisters. The student-worker-academic alliance was swift and effective. The unions, and staff associations soon joined students in calling for the decolonisation of universities’ under the slogan “Rhodesmustfall”.

A few months later and once more South Africa’s born-frees, a generation many would have relegated to the back-burners of history because of their unfortunate birth into a rainbow nation that afforded them no link to their past and no definite grasp on their future, entered the stage of history again. This time with even more courage, perseverance, and commitment than before. This time they were not content with protests and occupations alone, this time they had to shut the whole system down and call into question those fundamental freedoms that, they had been told, were secured just by the timing of their births. Free education for all was the new call to struggle, and everyone is responding.

At the moment, thousands of students all over the country are sitting at their respective universities, holding meetings, strategising, counselling each other, studying for exams and bracing themselves for another long day of resistance. They will be out on the streets again today loud, defiant, and accompanied by academics, unionists, support staff, church members and general supporters.

It is a moment, which is changing the political and social landscape of South Africa. The students have not much national direction or co-ordination. They have not collectively joined any national organisation, political party or student union, they are drawn from all classes, races and genders of society and from various political leanings, they have sat together in the thousands, usually outdoors in most cases, and ate together, sang together, worked together and faced bullets and tear gas together. Students have also fought, sometimes with each other, to maintain the focus also on issues of class and against the perpetuation of cheap black labour as the invisible hands that hold up the institution. The precarious economic positions of those workers that withstand the worst of outsourcing practices have also been at the centre of struggles to transform post-Apartheid institutions into African universities.

Gender equality

There has been an insistence from the beginning that any struggle for decolonisation must be intersectional and recognise not only the role played by women, but that transformation must have gender relations as central tenet. The constant feminist backlash has kept many movements from collapsing into reliance on patriarchal or misogynist leaders and leadership styles even if this is an on-going battle. Perhaps even more inspiring has been the fidelity to principles and values that foreground the collective spirit and decision-making practices of these movements. Rejecting and resisting co-optation or the tendency of management to divide and rule by attempting to single out student leaders and have private meetings, while remaining disciplined has proved their maturity and intellect time and time again.

Rather than dogmatic ideology or party membership, what has linked these movements and what sustains them is a collective feeling and understanding that something is terribly wrong in the university, and perhaps the humble assumption that it has, for a while now, been reflected in the society around and outside it. On the weekend, in Grahamstown students, academics and members of the community held a night vigil for those who have been affected by the recent xenophobic attacks on mostly, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Ethopian shop-owners. The Unemployed People’s Movement had informed the police a week prior that they were worried about rumours circulating amongst people in the township blaming foreigners’ for the recent deaths of some local women. The police had failed to act, they also failed to stop the looting or protect many of foreign shop – owners and their families who have now fled the town or are in hiding. Instead, they were present at the peaceful marches and protests of students on the Rhodes and Eastern Cape Midlands campuses using tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets on unarmed students while across town the widespread looting of shops and violence against foreigners raged on.

There is no doubt therefore, that what we are witnessing is a revolutionary political moment in history. Midnight’s children are learning to walk and talk. They are also learning that they have not been born free, and their freedom is necessarily and inextricably linked to the freedom of those around them. If sustained, this collective form of politics and mass mobilisation reminiscent of the 1980s people’s power movements could change the country’s political trajectory and demonstrate to Zuma and the shadowy figure of what was once the African National Congress that, as the shack dwellers movement Abahlali baseMjondolo puts it: "Amandla ngawethu inkani" – the power is ours by force.

Camalita Naicker is a doctoral scholar at Rhodes University, South Africa, and currently spending a semester at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

This article first appeared on Kafila.org.