Stay in Odisha for a bit and you will run into a puzzle.

Despite healthy finances, the state is failing to provide basic services to its people. Its schools and hospitals are badly understaffed. Jobs are not easy to find, as a result of which young people are getting disillusioned with education itself. Welfare programmes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme work only on paper.

While the state saw an iron ore boom over the last decade, government's policies ensured only a handful of people became rich. Most stayed unaffected. Some ended up poorer. During the same period, the state also saw a chit fund boom in which middle- and low-income families lost money.

Despite this streak of state failure, the state's people continue to be silent. To an outsider, the silence is striking. Said a senior IAS official in the state: “There is a passivity amongst the people. I have seen low-level government functionaries take Rs 50 off people who own no more than one set of clothes. And I could not understand. Why would one feel no qualms about taking money from someone so poor? Why did the other not protest?”

Abhijit Sen, who was overseeing Odisha when he was a member at the erstwhile Planning Commission, agreed with this characterisation. “The puzzling thing about Odisha is its great inertia,” he said. “The government moves slowly. And people assume that slowness is inherent. In that sense, yes, the population is passive.”

There is little political activism in the state, whether from its political parties, or from its people. What you see instead, said Sen, is a thriving informal sector with people who do whatever work they can get or simply migrate from the state to make ends meet.

What explains this?

Is it the people?

Puzzling over this question, Scroll.in met Kedar Mishra, poet and editor of Odiya monthly Sachitra Vijaya, one evening at the city's old bus stand. Abandoned after a larger bus station came up at the edge of the city, the centrally-located old bus stand has morphed into a bazaar selling garments, among other things. Every evening, Mishra and his friends meet at a tea-stand here for an adda.

Mishra traced a part of this passivity back to the state's history. An agglomeration of small, princely states, Odisha was always feudal. Things changed slightly after Independence, when coastal Odisha came to support the Congress party while the western and tribal parts of the state stayed loyal to the princely rulers-turned MLAs and MPs, regardless of which party they joined.

For the most part, said Mishra, the old way of thinking remained intact: "You talk to people and you get a mindset which says, 'I do not want to understand politics, rights, political rights, democracy, etc. I operate on the belief that the people I am choosing understand them.' It is a very lethargic society."

If anything, said Mishra, in recent years, Odiya society has seen further depoliticisation. This is partly the failure of the institutions that create a political consciousness – political parties, civil society and the media.

The structure of state politics

Every November, people leave Bolangir, a district in western Odisha, and head to Andhra Pradesh and beyond to work as bonded labour at brick kilns for six months.

Bolangir's MP, Kalikesh Singh Deo, hails from the royal family of Bolangir. Before entering politics, he worked as an investment banker and then at the energy firm Enron. Deo illustrates a larger reality. As Mishra said, “In Odisha, senior leadership of all parties is drawn from the same group. Even communist and socialist leaders are from the same high-caste groups and feudal families.”

In more recent times, businessmen have entered the fray as well. Said a veteran politician who left the Biju Janata Dal after a disagreement with Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik, “Being an MP or an MLA gives you access inside the government.”

This class bias in politics – seen across most of India – impacts Odisha in two ways. First, it throws up elected representatives who have little in common with those who vote for them. Second, as Mishra said, it dilutes the power of ideology. “You are not in a party for ideology but to be elected as MLA or MP,” he said. "It is all about your interest."

What about the opposition?

Apart from the ruling Biju Janata Dal, Odisha has the Congress, the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Left parties. Each of the opposition parties is weak, so much so that Naveen Patnaik's Biju Janata Dal is now in power for its 16th straight year.

Discussing them, the veteran politician was scathing. “The Congress is non-functional," he said. "The Bharatiya Janata Party is not useful opposition either. Both parties are bankrupt after having been out of power for so long.” As for the Left, it has fractured into 15 or so fragments.

Worsening matters, senior leaders from opposition parties have gradually moved to the ruling party, further enfeebling their original parties. Sometimes, they have done so with exceptional timing. Take the former state leader of the Congress, Bhupinder Singh, and its party secretary, Anup Sai. They joined the Biju Janata Dal a month before the state assembly election was held in April 2014.

Among the politicians who have not moved to the BJD, says Mishra, there is infighting. “No one is willing to accept anyone else as their leader if they are not from the same region.”

Given this context, said Mishra, several protests in the state – like where the Indian Institute of Management should be located – have been led by the bar association. “Political parties have proved to be subservient to them."

What about the fourth pillar?

Another stimulant to political discussion, as Mishra said, could have been the media.

But in Odisha, as in other parts of India, the press is sizeably owned by political families. In an article “Who does the media serve in Odisha?”, published this year in the Economic & Political Weekly, activist Sudhir Pattnaik, who edits an Odiya-language alternative magazine Samadrusti, says most powerful chief ministers in the state either owned or edited a newspaper.

This trend has accelerated post-liberalisation. For instance, the BJD's Baijyant Panda owns the news channel OTV. Samvad, an Oriya newspaper, is owned by Soumya Ranjan Patnaik, a former MLA and the brother of Niranjan Patnaik, a former head of the Congress in Odisha.

There is a larger point here. As the IAS official said, one curious aspect of modern Odisha is the almost hegemonic presence of a few families. According to the official, they straddle “the judiciary, media, business and politics”. For instance, Panda owns mining and steel company IMFA and OTV. Soumya Ranjan Patnaik, apart from being related to Niranjan Patnaik, is also related to Indrani Patnaik, who owns mining leases in the state.

In this situation, where businessmen or politicians are owner-publishers, said Mishra, “the publications function as mouthpieces. They provide MPs and MLAs a chance to promote themselves.” Or to protect themselves. Take the Serajuddin family, which owns mining leases in the state. It has just started a newspaper. One reason, said an employee close to the family, is the need for security. The family "started a paper as they were being targeted by others", this person said. "The idea is to have a paper we can use to defend ourselves.”

What adds complexity here is the lack of opposition. “All papers are overtly or covertly pro-BJD," said Mishra.

The journalism this creates, he said, is “subdued and subservient”.

“Small questions become very large," he explained. "Even when there is a large issue, the debate will be on something else. The Shah Commission report [on illegal mining] doesn't get discussed. What gets discussed are the religious babas. Whether the new IIT should come up in Cuttack or Bhubaneswar. Or, the smart city. The run-up to Jagannath Rath Yatra itself went on for four months.”

What about civil society

This leaves us with civil society groups.

Over the years, Odisha has seen several people's movements but most of them have been very localised, cropping up around specific issues like Niyamgiri, Hirakud or Kalinganagar.

Strikingly, Pattnaik pointed out that most of these movements have been started by the tribals. “The tribals are more assertive than the rest of the population.” This has been the pattern, he said, from colonial times. “The state was colonised by the British in 1803. It saw 144 years of British rule. In contrast, the tribals kept fighting, and managed to stay independent for 130 years. You do not find such stories from mainland Odisha.”

Apart from the localised movements, said Mishra, Odisha has not seen too many political movements which stretched across the state. “There was one only in the 1950s for language.”

The reasons for the lack of movements again can be traced back to weak leadership and the absence of political thinking. “Without that, you will not be able to take a movement up step by step," said Mishra. "Which is why the state has hundreds of movements but they are all very localised."

The poet also identified the middle class as the culprit. “It is demoralised and politically illiterate."

Added the veteran politician: “At one time, the Left used to conduct political training camps at the district level. Those have stopped now. How does one then infuse the idea of political democracy in the state?”

Another reason is the fracturing of identities in the state. “Tribal is different from coastal," this person said. "The people in Kendrapara do not like the people in Cuttack, who, in turn, do not like the people of Bhubaneswar. In that sense, a homogenous identity is yet to be formed.”

The media has contributed to the problem here, he said. “All papers now have five-seven regional editions. As news gets localised, fellow-feeling suffers.”

At the same time, the state government's crackdown on people's movements – slapping cases on activists branding them as Naxals – has also chilled dissent.

The contradiction of Naveen's Odisha

In Odisha, the perception is that Naveen Patnaik runs the government with the help of his bureaucrats, with his party MLAs having very little say. The editor of a leading newspaper said: “This is a bureaucrat-run government, not a politician-run one.” This shows in several ways – like the state's decision to report a revenue surplus each year, even if that means it doesn't appoint enough doctors or teachers. States where the government is led by politicians tend to pay greater heed to public services, even at the cost of running populist schemes and incurring revenue deficits. In contrast, Odisha is fiscally conservative, posting a revenue surplus of about Rs 5,000 crore.

This means taking one's complaints to the local MLA is not very useful. The only check on the government, said the veteran politician, comes from public interest litigation and the judiciary.

Benevolent feudalism

Take a closer look at Naveen Patnaik's government and you see a curious paternalism at work.

The state runs a multitude of welfare programmes – ranging from a public distribution system that covers most households in the state to providing free uniforms, cycles, laptops, mobile phones, blankets, saris, umbrellas, cash to families when someone dies at home, and more.

But it doesn't invest in teachers or doctors. It doesn't ensure quality higher education. And its policies concentrate wealth in a few families.

The outcome is a composite of rising aspirations, frustration as the state denies those, and a lack of political literacy.

According to Mishra, this ensures that the reactions of people are "always trivial". For a more considered view, he said, "you need motivation and thinking political people”.

According to Pravas Mishra, a researcher with Oxfam, the resulting desperation – of not having enough money or being unable to cure a loved one – is responsible for the state's chit fund and religious baba boom. “Unsure about the hospitals, people go to a Sarathi Baba hoping for a miracle," Mishra said. "It's the same reason they invested in chit funds.”

Others move out of the state – some looking for subsistence, others seeking better prospects. In a passive state, migration, then, is the only form of protest. And survival.

We welcome your comments at

letters@scroll.in.

Despite healthy finances, the state is failing to provide basic services to its people. Its schools and hospitals are badly understaffed. Jobs are not easy to find, as a result of which young people are getting disillusioned with education itself. Welfare programmes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme work only on paper.

While the state saw an iron ore boom over the last decade, government's policies ensured only a handful of people became rich. Most stayed unaffected. Some ended up poorer. During the same period, the state also saw a chit fund boom in which middle- and low-income families lost money.

Despite this streak of state failure, the state's people continue to be silent. To an outsider, the silence is striking. Said a senior IAS official in the state: “There is a passivity amongst the people. I have seen low-level government functionaries take Rs 50 off people who own no more than one set of clothes. And I could not understand. Why would one feel no qualms about taking money from someone so poor? Why did the other not protest?”

Abhijit Sen, who was overseeing Odisha when he was a member at the erstwhile Planning Commission, agreed with this characterisation. “The puzzling thing about Odisha is its great inertia,” he said. “The government moves slowly. And people assume that slowness is inherent. In that sense, yes, the population is passive.”

There is little political activism in the state, whether from its political parties, or from its people. What you see instead, said Sen, is a thriving informal sector with people who do whatever work they can get or simply migrate from the state to make ends meet.

What explains this?

Is it the people?

Puzzling over this question, Scroll.in met Kedar Mishra, poet and editor of Odiya monthly Sachitra Vijaya, one evening at the city's old bus stand. Abandoned after a larger bus station came up at the edge of the city, the centrally-located old bus stand has morphed into a bazaar selling garments, among other things. Every evening, Mishra and his friends meet at a tea-stand here for an adda.

Mishra traced a part of this passivity back to the state's history. An agglomeration of small, princely states, Odisha was always feudal. Things changed slightly after Independence, when coastal Odisha came to support the Congress party while the western and tribal parts of the state stayed loyal to the princely rulers-turned MLAs and MPs, regardless of which party they joined.

For the most part, said Mishra, the old way of thinking remained intact: "You talk to people and you get a mindset which says, 'I do not want to understand politics, rights, political rights, democracy, etc. I operate on the belief that the people I am choosing understand them.' It is a very lethargic society."

If anything, said Mishra, in recent years, Odiya society has seen further depoliticisation. This is partly the failure of the institutions that create a political consciousness – political parties, civil society and the media.

The structure of state politics

Every November, people leave Bolangir, a district in western Odisha, and head to Andhra Pradesh and beyond to work as bonded labour at brick kilns for six months.

Bolangir's MP, Kalikesh Singh Deo, hails from the royal family of Bolangir. Before entering politics, he worked as an investment banker and then at the energy firm Enron. Deo illustrates a larger reality. As Mishra said, “In Odisha, senior leadership of all parties is drawn from the same group. Even communist and socialist leaders are from the same high-caste groups and feudal families.”

In more recent times, businessmen have entered the fray as well. Said a veteran politician who left the Biju Janata Dal after a disagreement with Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik, “Being an MP or an MLA gives you access inside the government.”

This class bias in politics – seen across most of India – impacts Odisha in two ways. First, it throws up elected representatives who have little in common with those who vote for them. Second, as Mishra said, it dilutes the power of ideology. “You are not in a party for ideology but to be elected as MLA or MP,” he said. "It is all about your interest."

What about the opposition?

Apart from the ruling Biju Janata Dal, Odisha has the Congress, the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Left parties. Each of the opposition parties is weak, so much so that Naveen Patnaik's Biju Janata Dal is now in power for its 16th straight year.

Discussing them, the veteran politician was scathing. “The Congress is non-functional," he said. "The Bharatiya Janata Party is not useful opposition either. Both parties are bankrupt after having been out of power for so long.” As for the Left, it has fractured into 15 or so fragments.

Worsening matters, senior leaders from opposition parties have gradually moved to the ruling party, further enfeebling their original parties. Sometimes, they have done so with exceptional timing. Take the former state leader of the Congress, Bhupinder Singh, and its party secretary, Anup Sai. They joined the Biju Janata Dal a month before the state assembly election was held in April 2014.

Among the politicians who have not moved to the BJD, says Mishra, there is infighting. “No one is willing to accept anyone else as their leader if they are not from the same region.”

Given this context, said Mishra, several protests in the state – like where the Indian Institute of Management should be located – have been led by the bar association. “Political parties have proved to be subservient to them."

What about the fourth pillar?

Another stimulant to political discussion, as Mishra said, could have been the media.

But in Odisha, as in other parts of India, the press is sizeably owned by political families. In an article “Who does the media serve in Odisha?”, published this year in the Economic & Political Weekly, activist Sudhir Pattnaik, who edits an Odiya-language alternative magazine Samadrusti, says most powerful chief ministers in the state either owned or edited a newspaper.

This trend has accelerated post-liberalisation. For instance, the BJD's Baijyant Panda owns the news channel OTV. Samvad, an Oriya newspaper, is owned by Soumya Ranjan Patnaik, a former MLA and the brother of Niranjan Patnaik, a former head of the Congress in Odisha.

There is a larger point here. As the IAS official said, one curious aspect of modern Odisha is the almost hegemonic presence of a few families. According to the official, they straddle “the judiciary, media, business and politics”. For instance, Panda owns mining and steel company IMFA and OTV. Soumya Ranjan Patnaik, apart from being related to Niranjan Patnaik, is also related to Indrani Patnaik, who owns mining leases in the state.

In this situation, where businessmen or politicians are owner-publishers, said Mishra, “the publications function as mouthpieces. They provide MPs and MLAs a chance to promote themselves.” Or to protect themselves. Take the Serajuddin family, which owns mining leases in the state. It has just started a newspaper. One reason, said an employee close to the family, is the need for security. The family "started a paper as they were being targeted by others", this person said. "The idea is to have a paper we can use to defend ourselves.”

What adds complexity here is the lack of opposition. “All papers are overtly or covertly pro-BJD," said Mishra.

The journalism this creates, he said, is “subdued and subservient”.

“Small questions become very large," he explained. "Even when there is a large issue, the debate will be on something else. The Shah Commission report [on illegal mining] doesn't get discussed. What gets discussed are the religious babas. Whether the new IIT should come up in Cuttack or Bhubaneswar. Or, the smart city. The run-up to Jagannath Rath Yatra itself went on for four months.”

What about civil society

This leaves us with civil society groups.

Over the years, Odisha has seen several people's movements but most of them have been very localised, cropping up around specific issues like Niyamgiri, Hirakud or Kalinganagar.

Strikingly, Pattnaik pointed out that most of these movements have been started by the tribals. “The tribals are more assertive than the rest of the population.” This has been the pattern, he said, from colonial times. “The state was colonised by the British in 1803. It saw 144 years of British rule. In contrast, the tribals kept fighting, and managed to stay independent for 130 years. You do not find such stories from mainland Odisha.”

Apart from the localised movements, said Mishra, Odisha has not seen too many political movements which stretched across the state. “There was one only in the 1950s for language.”

The reasons for the lack of movements again can be traced back to weak leadership and the absence of political thinking. “Without that, you will not be able to take a movement up step by step," said Mishra. "Which is why the state has hundreds of movements but they are all very localised."

The poet also identified the middle class as the culprit. “It is demoralised and politically illiterate."

Added the veteran politician: “At one time, the Left used to conduct political training camps at the district level. Those have stopped now. How does one then infuse the idea of political democracy in the state?”

Another reason is the fracturing of identities in the state. “Tribal is different from coastal," this person said. "The people in Kendrapara do not like the people in Cuttack, who, in turn, do not like the people of Bhubaneswar. In that sense, a homogenous identity is yet to be formed.”

The media has contributed to the problem here, he said. “All papers now have five-seven regional editions. As news gets localised, fellow-feeling suffers.”

At the same time, the state government's crackdown on people's movements – slapping cases on activists branding them as Naxals – has also chilled dissent.

The contradiction of Naveen's Odisha

In Odisha, the perception is that Naveen Patnaik runs the government with the help of his bureaucrats, with his party MLAs having very little say. The editor of a leading newspaper said: “This is a bureaucrat-run government, not a politician-run one.” This shows in several ways – like the state's decision to report a revenue surplus each year, even if that means it doesn't appoint enough doctors or teachers. States where the government is led by politicians tend to pay greater heed to public services, even at the cost of running populist schemes and incurring revenue deficits. In contrast, Odisha is fiscally conservative, posting a revenue surplus of about Rs 5,000 crore.

This means taking one's complaints to the local MLA is not very useful. The only check on the government, said the veteran politician, comes from public interest litigation and the judiciary.

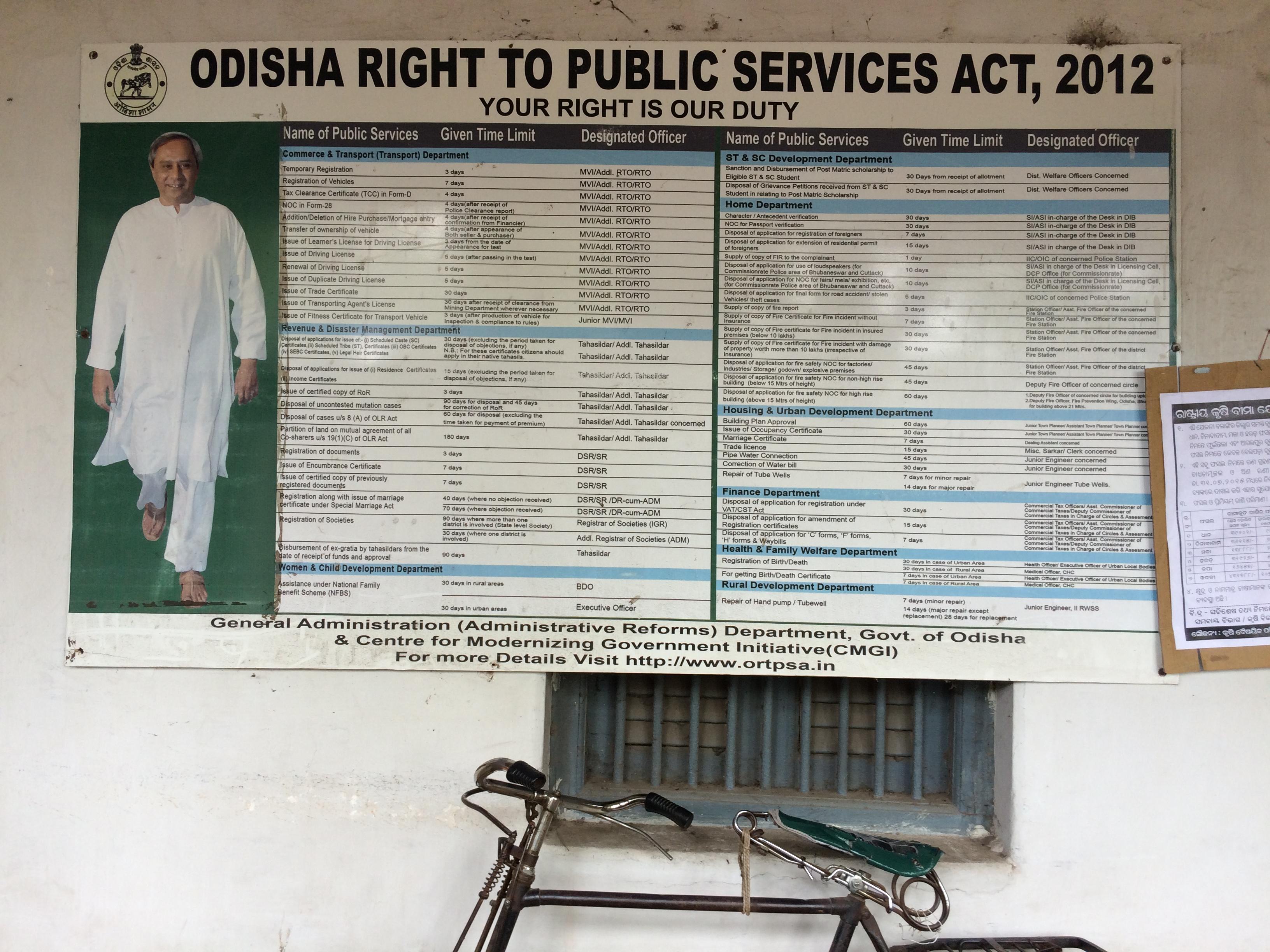

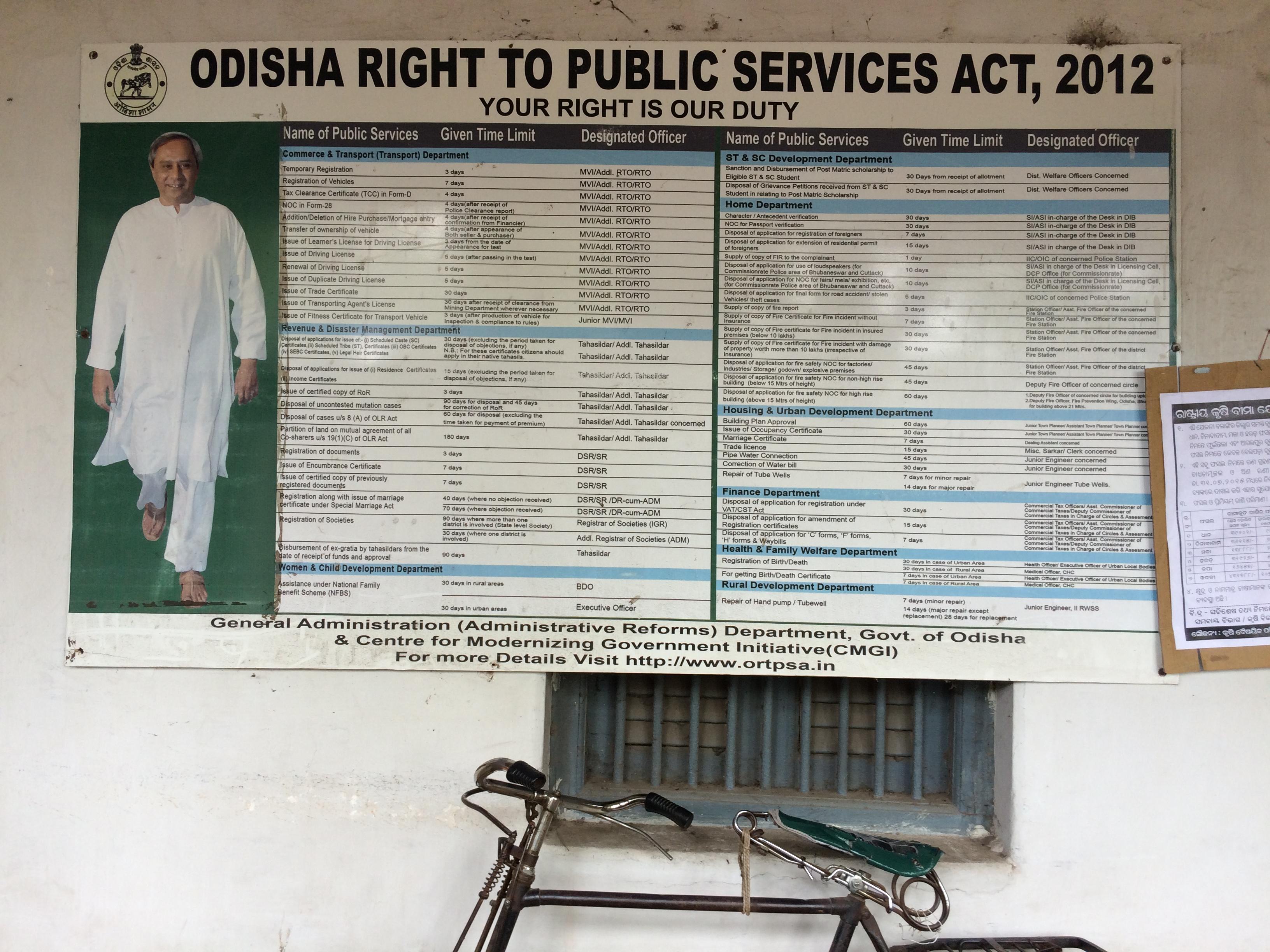

A government poster, pasted onto the wall at the collector's office in Bolangir, promises prompt service delivery

Benevolent feudalism

Take a closer look at Naveen Patnaik's government and you see a curious paternalism at work.

The state runs a multitude of welfare programmes – ranging from a public distribution system that covers most households in the state to providing free uniforms, cycles, laptops, mobile phones, blankets, saris, umbrellas, cash to families when someone dies at home, and more.

But it doesn't invest in teachers or doctors. It doesn't ensure quality higher education. And its policies concentrate wealth in a few families.

Children in a government school. Interior Odisha suffers from an acute shortage of teachers.

The outcome is a composite of rising aspirations, frustration as the state denies those, and a lack of political literacy.

According to Mishra, this ensures that the reactions of people are "always trivial". For a more considered view, he said, "you need motivation and thinking political people”.

According to Pravas Mishra, a researcher with Oxfam, the resulting desperation – of not having enough money or being unable to cure a loved one – is responsible for the state's chit fund and religious baba boom. “Unsure about the hospitals, people go to a Sarathi Baba hoping for a miracle," Mishra said. "It's the same reason they invested in chit funds.”

Others move out of the state – some looking for subsistence, others seeking better prospects. In a passive state, migration, then, is the only form of protest. And survival.