“As Sharad Joshi ji fell, farmers below tried to dampen the fall, but it was steep and he did suffer injuries," recalled Bhupinder Singh Mann of Bhartiya Kisan Union. "That fellow Tikait threw Joshi ji himself.”

But why?

“Even today we don’t know," he said. "We had already agreed to all of Tikait's demands. He wanted to smoke his hukkah on stage and we agreed to even that..."

Mann, who is now the chairman of the Kisan Coordination Committee, speculated further. “You see the system is based on exploitation and so anyone who exposes it threatens the existence of many in power," he said. "I tell you the history of India would have been different today had that incident not taken place.”

Unlike Tikait, a rustic head of a village Khap panchayat, Joshi was an educated economist, and a farm leader of the sort India had not seen. Not only did he have slick agitational skills, he had the power of reasoning and economics to convince a farmer about free markets and freedom. More importantly, he could make a farmer think.

An encounter with Minoo Masani

In a strange co-incidence, I have been privy to Sharad Joshi’s political journey since the early nineties and it became my own. As a school student in Darjeeling in 1988, I read an interview with Minoo Masani titled "Always Against The Tide". A member of the assembly that framed India’s Constitution, Masani had co-founded Swatantra Party in 1959 with C Rajgopalachari, India’s first and only governor general, to oppose Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialist economic policies.

With its slogan "Farm, Family and Freedom, the Swatantra Party wanted a liberal free market economy and an end to the Licence, Permit Quota Raj where a few businessmen were favoured while others denied permissions to set up enterprises. At its peak in 1967, it was India’s largest opposition party with 44 members of Parliament.

As chance would have it, I found myself studying history at Mumbai's St. Xavier’s College, and in 1990 through a lucky draw, I was part of a team that had to make a presentation on the economic policies of Jawaharlal Nehru.” I dialled a telephone number from an MTNL directory at a pay phone after dropping in a Re 1 coin. “This is Masani speaking,” said the voice at the other end. I asked for an interview. He asked, “Regarding?” I replied, “Economic policies of Jawaharlal Nehru." His crisp voice, “Disastrous. Come and see me at 10 am at the Army & Navy Building.”

The next morning we met Masani. It was an education we had not received in the classroom. One question that dominated our minds was whether the Swatantra Party could be revived. “Good things don’t happen twice," replied Masani. "But India needs what the party stood for. I don’t know but maybe Sharad Joshi could do it or may be some young farmers from rural India.”

Sharad Joshi, an economist by training, was already a prominent farmer leader but he had no Swatantra connection. Born Sharad Anantrao Joshi on September 3 1935 in Satara, Maharashtra, his father was Anant Narayan and mother Indirabai Joshi. He did a Masters in Commerce from Sydenham College in 1957 and a diploma in Informatics from Lausanne, 1974. A brilliant student he joined the Indian Postal Service and worked with them from 1958 to 1968. He then joined the United Nations as its Chief of Information Bureau in Switzerland. It was at his UN assignment that he got to travel around the world and see how farmers everywhere, including India, were at the bottom of the pyramid. He was also disturbed when he saw Indian politicians travelling abroad to seek international aid.

Sharad Joshi in his younger days.

Return to roots

In 1976, Joshi quit his lucrative career at the United Nations to return to India to become a farmer. He bought a plot of land at Ambethan, near Pune, in January 1977, to experience farming first hand. Keeping meticulous accounts at his farm and understanding the markets, he realised within two years that farming was a losing proposition. He also understood how it was the government's deliberate policy to keep farm prices depressed. He studied India’s rural economy and found a negative subsidy of 72% on the cost of agriculture production. This prompted him to set up the Shetkari Sangathana in 1979 in Chakan near Pune to demand remunerative prices for farm produce and access to markets and technology.

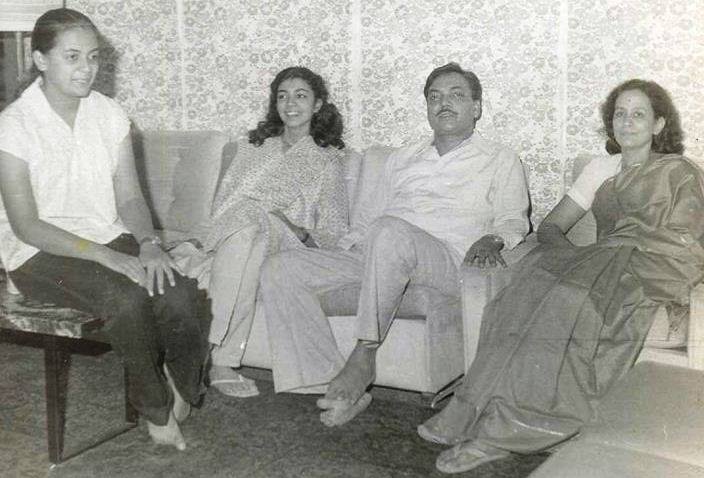

Joshi with his family.

In 1979, onion prices had crashed in India and there was a government ban on the export of onions. Farmers began protests, with the first demonstrations at Chakan. Joshi was arrested. By November 1980, the farmers protests spread to Nasik. Joshi led the agitation, blocking road and rail, until the police arrested him again. His colleague for 35 years, Sureshchandra Mhatre recalled, “We did not indulge in violence but the police opened fire. Some farmers were killed.”

Not many had heard of Sharad Joshi then and nobody came to see him in prison. Except one day he had a visitor. Minoo Masani. Masani had been observing this agitation and gave moral support to the farmers.

Fighting for fair remuneration

The Shetkari Sangathana opposed farm subsidies but highlighted the fact that the Indian government practiced a negative subsidy – for every Rs 180 a farmer spent he got back only Rs 100. “We did not want alms but rather a return on our sweat and toil," said Mhatre. The Sangathana grew to a strong ten lakh membership across Maharashtra. From onion to cotton to tobacco to sugarcane to paddy and wheat, the 1980s saw farmers agitations across Maharashtra to Punjab and even to the Wagah border when farmers tried to cross over with their wheat to Pakistan.

In 1986, Joshi set up a women’s wing called Shetkari Mahila Aghadi – perhaps the largest rural women organisation in India, celebrated for its Lakshmi Mukti program that fought for property rights for rural housewives. Some two lakh rural women gained property rights and even those who did not have land made their wives partners in their source of other income. Getting a raw deal from the then Congress governments, Joshi supported VP Singh, the leader of the Janata Dal. Once Singh became prime minister in 1989, he appointed Joshi as an advisor on agriculture. But before Joshi could submit a report on national agricultural policy, the government fell.

Reviving Swatantra Party

Joshi soon realised that his closest sympathiser was the erstwhile Swatantra Party, which had dissolved itself in the early 70's to become the Janata Party to take on Indira Gandhi. But Masani was opposed to this single-point merger and kept the Swatantra Party alive in Maharashtra and some other states. In the early nineties, it was decided to revive the Swatantra Party but by then an amendment in the Representation of People's Act required all political parties to re-register and swear allegiance to the Indian Constitution. This created a problem for Swatantra Party as it was opposed to socialism.

The original preamble to India’s Constitution did not have the word "socialism" but Indira Gandhi had included the word during the Emergency of 1975, as also the word "secularism". The Swatantra Party filed a writ petition in the Bombay High Court in 1994 challenging the clause of the Representation of the People Act that requires parties to swear allegiance to principles of socialism. The case came up for hearing only once in 20 years but when it did come before the judge, the judge excused himself as he had been a lawyer for the Swatantra Party.

Joshi and Masani

In the early '90s, Masani in “An Open Letter To My Young Friends” expressed fears that India’s liberalisation could be stalled if a liberal movement was not launched. Sharad Joshi accepted the call. The Shetkari Sangathana already had five MLAs in the Maharashtra assembly from 1990 to 1995, including a deputy speaker of Maharashtra Assembly. A public meeting was organised at Mumbai's Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan to revive the Swatantra Party. A frail Masani, by then in his eighties, walked in to a standing ovation to support Joshi’s efforts.

At the time Mandal-Masjid politics dominated the discourse and Joshi’s Swatantra Bharat Party was not even given a common symbol. Only two of his men won but they sat on the opposition benches for a full five-year term without being lured by the Shiv Sena-Bharatiya Janata Party government. I felt a hope for India.

Entering Parliament

In 2004, a group of liberals extended support to Joshi to expand on the national stage and lead Indian liberals. But ten days later, he held a press conference with Pramod Mahajan of the Bharatiya Janata Party, announcing his decision to support the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government in exchange for a Rajya Sabha seat. I opposed this and wrote "An Open Letter To Sharad Joshi" published in Freedom First magazine, an independent journal founded in 1952 by Minoo Masani to espouse liberal values. It was a heartfelt letter in which I reminded Joshi that he was a torch-bearer of a great party like the Swatantra and an opportunistic alliance with a communal political party like the BJP was a short-cut to Parliament but that short cuts do not pay or lead to success.

The letter provoked much debate among India's liberals. It surprised me but unlike other politicians, Joshi replied to me personally, apart from sending a reply to the journal. ”The letter looks personal and hence I reply to you personally,” he wrote. By then, he had become a Rajya Sabha MP with support of the BJP. I travelled to Delhi to meet him, and thought he would never show up. But there he was already seated at 8 am, taking on the criticism point by point.

He said he agreed with me a 100% about going it alone but said that he sat next to LK Advani without compromising on his liberal ideals just like Nitish Kumar did without compromising on secularism. His only aim to enter Parliament, he said, was to present a bill to challenge the Representation of People's Act on the socialism clause. Joshi did present a private member bill arguing how India’s liberals have been banned from contesting elections and so democracy itself is at stake. The bill was defeated. Sharad Joshi, a leader with the backing of a million farmers, never sought re-election to India’s Parliament.

Joshi's final journey on a tractor in Pune.

Sharad Anantrao Joshi (1935-2015)