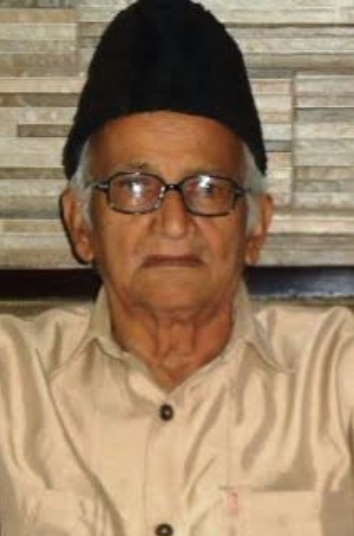

Asrar Jamayee, 80, an eminent Urdu poet, was declared dead by the Social Welfare Department of South Delhi in 2013, depriving him of his monthly pension of Rs 1,500. Since then, he has been fighting for survival. He lives alone in a rented single room littered with Urdu books (including his newly published ones, which lie under a thick layer of dust) and worn-out shervanis.

Since 2013, he has asked successive Delhi governments under Sheila Dikshit and Arvind Kejriwal for help, but to no avail. When he first appeared at the Social Welfare Department to prove that he qualified for old age pension, the officers there became belligerent.

“I told them, ‘I am standing in front of you, what could be greater proof [that I am alive]?” he said. “The official replied that he knew that I was alive, but he couldn’t help me because the records insisted I was dead.”

Jamayee has devoted his life to Urdu. He has published four books of poetry and booklets on Indian history. He also used to publish an entertaining Urdu fortnightly, Post Mortem, that contained caricatures of the who’s who of the city. Until recently, he was invited to mushairas in Delhi, but now the invitations are rare – he is considered too old to travel and address crowds. I have known him for almost a quarter of a century. I help him type out his poems and his signature visiting cards, which contain satirical couplets on contemporary issues, like this one on the paucity of drinking water:

“Jis desh mein Ganga behti hei/ Us desh mein pani bikta hei.”

Ganga flows on the Indian land/ Ironically, potable water, here is sold.

But contrary to what the mushaira committees may believe, Jamayee is actually fit to travel around the city – he often drops in at my place in Zakir Nagar, from where he buys his food from Javed Nahari Wala. Often, I tell him that he can eat at my home, but despite his frail appearance, he has a towering self-esteem (like most Urdu poets), and he never agrees to my request. Even today, he walks with great difficulty, but insists on distributing these couplet-visiting-cards to his acquaintances, especially the ones he likes.

It is tragic that none of the big Urdu platforms, like the National Council for the Promotion of Urdu Language, Urdu Academy, Ghalib Academy, and highly circulated Urdu newspapers like Inquilab, Rashtriya Sahara, Sahafat, Hamara Samaj, Hindustan Express, Jadeed Khabar, Jung Delhi and Mera Watan, all of which are based in Delhi and know about Jamayee’s plight, no longer bother about him.

This was not always the case. When he was young, Jamayee received an award from the first Indian President, Dr Rajendra Prasad. Everyone from APJ Abdul Kalam, Rajiv Gandhi, Karpoori Thakur (who was chief minister of Bihar between 1970 and 1971) and Lalu Prasad Yadav – all admirers of satire, invited him to recite his poetry at official and private functions. But there is no one lonelier than a poet past his prime. Pointing at his shervani the other day, Jamayee said, “Gone are the days when these used to travel to Dubai, Kuwait and Europe.”

Jamayee was born in Patna in 1937 as Abrar-ul-Haq. His father Syed Wali-ul-Haq was a zamindar who was part of the Khilafat Movement and a companion of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Maulana Mohammed Ali Jauhar. Jamayee studied at New Delhi’s Jamia Milia Islamia under the tutelage of Dr Zakir Hussain, the celebrated Urdu scholar who would go on to become president of India. Impressed by Jamayee, Hussain asked his protege to study engineering at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science in Pilani, while carrying on with his passion for poetry. It was at this time that Abrar-ul-Haq added the moniker “Jamayee” to his name. Encouraged by Hussain, he began to recite his poetry at public gatherings.

Jamayee was in college when he received news of his father’s death and returned to Patna. He started an institute to coach young aspirants training for entrance exams in medicine and engineering. The next few years were full of suffering: property disputes, discord in the family and the death of his mother.

As a result, he never married, and poetry became his first and only love. When Jamayee returned to Delhi to find that his room had been occupied by goons, he lamented the loss of his books and publications more than having no place to to live. He still frequently brings up this loss.

Jamayee deserved an award like the Padma Shri or the Urdu Academy Award for his poetry, but each time, he lost out to candidates who were better at lobbying for awards and favours. Last winter, he fell sick and stopped venturing out of his house in the cold. Like the pension officers, many of his neighbours and friends like me also came to believe that perhaps he had died. The poet writes in Tanzparey, his latest humorous book:

“Hamdardi ki lazzat bantey rahey hein khushion ke paimaney mein/ Kitney dukhi insan hein, yeh koi nahin pehchaney he/ Mulkon, mulkon, basti, basti shor hamari jurrat ka/ Bachcha, buddha, buddha, tanz hamari janey hei!”

They are partying all and celebrating with goblets full of happiness/ No one knows the trauma and angst of my life’s sadness/ O, the bravery and boldness of my poetry is internationally known/ Why talk of adults, even the children are aware of my sadistic groan!

— Asrar Jamayee

When Jamayee visited the local MLA’s office for his pension in 2015, he was treated shoddily – he received a cheque from the Jammu and Kashmir Bank for Rs 1,000 but the cheque bounced and was never honoured, despite several visits to the bank.

“Shayar, adeeb aap se jaltey hein kis liye/ Poochha to boley Jamayee, mukhlis hein sab merey/ Jaisey ke ek chiragh se jaltey hein kuchh chiragh/ Shayar, adeeb mujh se bhi jaltey hein is liye!”

— Asrar Jamayee

Why are poets and writers envious of me/ Know you all that I am a well wisher of thee/ The way one lamp lights another/ That I might walk away with an award, they are scared!”

Since he keeps falling sick and is alone, Jamayee has looked for accommodation in Delhi’s old age homes, but cannot afford the high fees there.

“Samjhoge usey kaisey, jo Asrar he Haq ka/ Asrar ka Asrar faqat naam nahin hei!”

— Asrar Jamayee

It’s not easy to understand the righteousness in his name/ Eternal is the secret of the truth of Asrar’s fame.

A version of this article first appeared on Sabrang India.