Photos: Of Independence-era iconoclasts, only suit-boot Ambedkar iconography stands test of time

Across India, disrespect for public art signals a deep change in the social and political landscape.

Defaced faces of Nehru and Gandhi, Hyderabad.

I couldn’t help but reflect on my childhood in the 1960s and '70s. Statues of these men were everywhere to be seen, often with garlands of fresh gladiolas around their necks. This version of the Fathers of Independent India would have been unimaginable a few decades ago. Not everyone agreed with Nehru’s politics or Gandhi’s philosophy, but no one openly disrespected them for what they had done to achieve freedom.

As I travel across India, I have noticed how public art signals a deep change in India’s social and political landscape. The defaced statutes in Hyderabad were not unique. I noticed similar things in other cities. In Chennai, a mural depicting some of the great heroes of Independence included an image of K Kamraj, the Gandhi of the South. Like Gandhi, he was a social reformer. And like the Mahatma he invoked humanitarian ideas as a way to fight untouchability. In the mural, Kamraj’s mouth is also stained with shit.

A defaced poster of Kamraj, Nehru and Gandhi, Chennai.

At the same time, it seemed everywhere I turned I was confronted with Dr Ambedkar. Though he was one of Independent India’s most formidable intellectuals and served in the Nehru cabinet, he was never comfortable within the Congress Party. He never ceased sparring with Gandhi and his paternalistic approach to Dalit liberation. He not only abandoned the Congress but the Hindu faith as well. He converted to Buddhism and urged his followers to do the same.

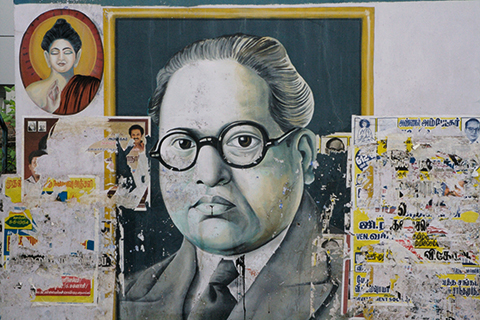

Public mural of Babasaheb Ambedkar, Chennai.

Growing up in India during the first post-Independence generation I was certainly aware of Dr Ambedkar, but he was a minor star in the Independence constellation. I certainly had no appreciation for Babasaheb’s wonderful glasses. As round and as big as a pair of astrolabes, they instantly draw you into his serious, intense eyes.

A statue in a dalit housing colony in Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu.

In every painting, sculpture, painting or poster of Babasaheb I’ve encountered in my recent visits the glasses are emphasised. As if the artists were reassuring all those around that the great man was keeping an eye on his people. And warning all those who would perpetuate atrocities against them. At every chowk, in every gali, and along every main road in India, his amazing spectacles bear witness and keep vigil. Babasaheb, it seems to me, has replaced Bapuji as the Father of India. His face, full of protection and hope, has superseded the once laughing, but now night-soiled face of Mahatma.

A poster of Ambedkar on a wall next to an optician’s shop, Old Delhi.

When one compares the legacies of the two men, Ambedkar’s is arguably the more robust of the two. Gandhi’s great achievement of Independence is now taken for granted. Ambedkar’s vision, sharpened through his wonderful spherical rims, of Dalits doing it for themselves, of breaking loose of the mainstream political parties, of dictating their own terms, of electing their own leaders, not those chosen for them by non-Dalits, of choosing their own religion and not putting up with being pushed out of Hindu temples, is a vibrant and growing reality in modern India.

Love them or loathe them, Mayawati, Mulayam Singh Yadav and Kanshi Ram, have done more to change the face of Indian politics than the hacks of the Congress or Bharatiya Janata Party.

Chai shop mural, Kolkata.