On Tuesday, hundreds of workers from the Garment and Fashion Workers Union, which represents labour from most of the major garment factories in the state, organised a day-long protest in Chennai to demand that the wage increase announced in February – around Rs 3,000 more than the average garment industry wages announced in 2004 – be actually implemented on the ground.

As of now, workers in garment factories are still getting paid between Rs 4,000 and Rs 6,000 a month, based on the range of minimum wages stipulated by the Tamil Nadu government’s labour and employment department in 2004. These 2004 wages were themselves implemented only in 2012, after several years of agitation by the Garment and Fashion Workers Union.

The garments manufactured in these factories – by more than two lakh workers in Chennai alone – are supplied to several prominent, high-end international brands from the US, Europe and Japan, say union workers.

Such delays and violations in the payment of minimum wages to labourers are neither new nor surprising, but the ongoing protests by the garment workers in Chennai reveal the abysmal and arbitrary pay scales that workers across India are forced to survive on, despite rising costs of living.

Minimum wages in India are determined by different states under the Minimum Wages Act of 1948. “India does not have a common minimum wage policy that cuts across different industries,” said Sujata Mody, president of the Garment and Fashion Workers Union. “We have a backward policy in which wages are arbitrary and different for different states, regions, sectors and genders.”

In Tamil Nadu’s garment sector itself, for instance, the monthly minimum wage for a tailor is supposed to be Rs 5,600 in big cities, Rs 5,500 in smaller municipalities and Rs 5,300 in towns and villages. A supervisor in the same factory is supposed to get around Rs 100 more respectively in each of the three zones.

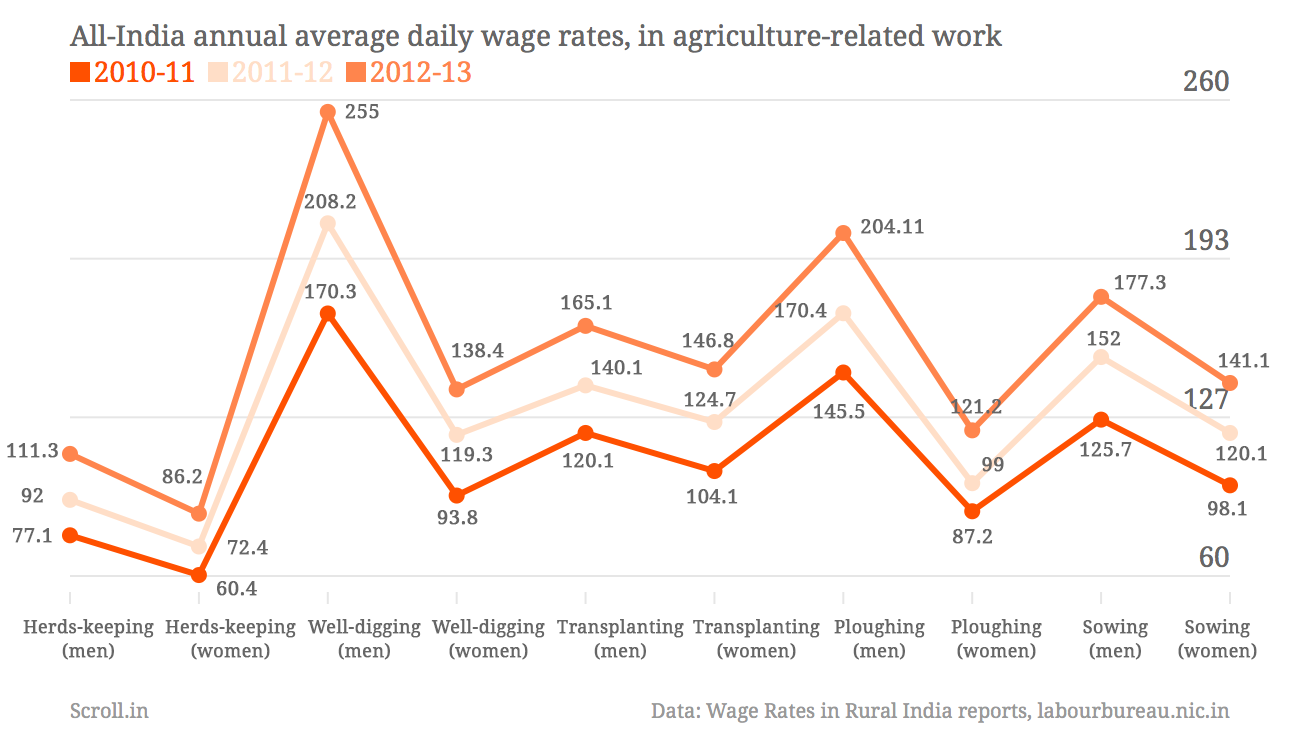

Across India, the minimum wages differ for different types of agricultural and non-agricultural work, and wages for the same kind of work are different for men and women. Here are the daily wage rates, in rupees, for agricultural and non-agricultural work from 2010 to 2013 in rural India:

The fluctuations are even more pronounced when one compares different states in India. Since 2010, Kerala has consistently been paying the highest average daily wage rate to rural workers, while Madhya Pradesh has been paying the lowest wages.

Such wages are rarely enough to sustain an average-sized family, but on the ground, the situation worsens for labourers because employers often fail to pay them even the full minimum wage.

“On an average, I would say that 70% of workers in India are being paid less than the minimum wage,” said Gautam Mody, general secretary of the Delhi-based New Trade Union Initiative.

There are also a vast number of violations under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, says Mody, which pays workers based on the amount of work they have done rather than the number of hours they work. If some kinds of work are more time consuming and lead to a smaller quantity of finished work, the payment is then reduced for workers. This, says Mody, is against the spirit of the Minimum Wages Act, which clearly states that no worker should be paid less than the minimum wage.

“There is rampant violation of the Act in India and complete failure of the government to implement it,” said Mody.

In Chennai, while garment workers still wait for the pay increase that the government has promised them, they are also pushing for an overall increase in minimum wages. “The current wages make it difficult for workers to afford rent, food and other basic expenses, so we are hoping to get at least Rs 10,000 a month,” said Meghna Sukumar, a member of the Garments and Fashion Workers Union.