On Monday, the Supreme Court said it would not take up a Public Interest Litigation seeking to strike down Rajasthan’s ordinance changing the qualification requirements for panchayat and zila parishad elections. The apex court said that challenges to the amended law, which mandates a Class X pass certificate for panchayat candidates and Class VIII for zila parishads, would have to be taken up in the Rajasthan High Court.

That court has put the matter up for next week, but there is one problem: elections are set to be held in three phases this month, and the notification by the state election commission has already been made. This makes it unlikely that the court will interfere with the ongoing election process.

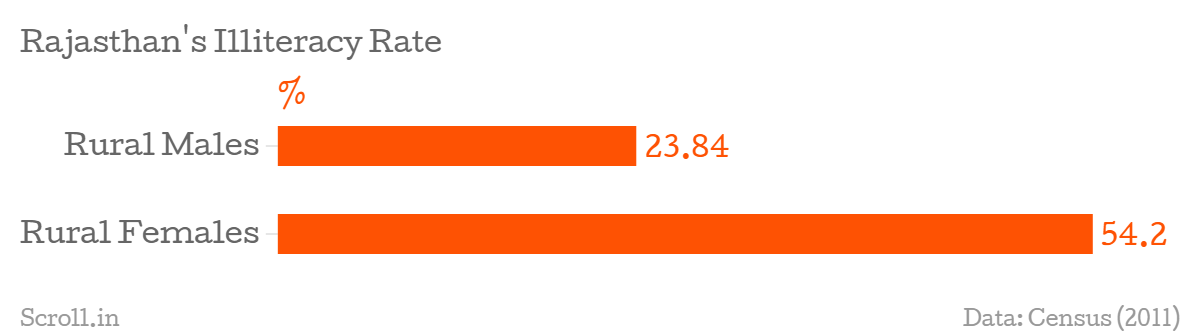

It means one other thing: nearly three-fourths of Rajasthan’s rural population and more than half of its women will not be allowed to contest in the local elections.

What’s in the ordinance?

On December 20, with the election notification days away, the Rajasthan government brought in an ordinance amending the Panchayati Raj Act, which laid down further qualifications for who could contest local elections. Earlier in the year, it had made it mandatory for all candidates to have toilets at home.

That change was made in the state assembly. This one, however, came through an executive ordinance that mandated a Class X certificate for anyone contesting panchayat polls and a Class VIII certificate for zila parishad candidates. In one fell swoop, as it were, a huge swathe of Rajasthan’s population was made ineligible to contest elections.

Those opposed to the ordinance, which includes all the parties opposed to the Bharatiya Janata Party, a number of civil society organisations and even some supporters of the government, have claimed that up to 80% of the rural population is now automatically disqualified. Since exact data on this may not be available, a look at the literacy rate alone should do the job.

It naturally gets worse if you look at specific portions of the state, with only 9.1% of Rajasthan’s significant scheduled tribe population having passed Class X. The rules are relaxed for scheduled seats, but not by a huge amount. In effect, what this ordinance will do is to automatically privilege upper-class, upper-caste men and make it much harder for others to contest elections.

How would it affect current lawmakers?

According to those who oppose the ordinance, the changes would not just disqualify a huge portion of Rajasthan’s population. It would also have made ineligible a number of those who are currently in the local bodies, and even BJP Members of Legislative Assembly, Members of Parliament and Cabinet ministers.

“Twenty-three of your own BJP MLAs in the current Vidhan Sabha are below 10th pass, as are two BJP MPs from Rajasthan,” wrote about 100 opponents of the ordinance, including two former central election commissioners in an open letter to the Rajasthan Chief Minister. “At the same time, almost 20% of the Cabinet Ministers at the Centre are below 12th Pass. Surely, if the Prime Minister finds MPs with such low educational qualifications suitable to devise and implement policies for the entire country, a Sarpanch of a small Gram Panchayat need not be held to such arbitrary and exclusionary standards.”

No other state includes such requirements for candidates to local elections or even to the Legislative Assembly and further up.

How did it get issued?

This part is crucial. The changes to the law were not tabled in the state assembly and so did not get discussed. The BJP has a two-thirds majority in the state House, so, unlike in the Rajya Sabha, it does not have the excuse of an uncooperative opposition to blame for not tabling the proposed legislation.

Most importantly, the ordinance was promulgated barely two weeks before the last day of nominations was set to happen and while the courts were during their winter break. Any challenge, then, was unlikely to stand in the way of the current election process, with polls set to begin on January 16.

The Central government’s ordinances, which have also received plenty of flak, are equally impactful, except for a crucial difference. It will be possible to overturn the changes that have been made to the Land Acquisition Act when it is eventually tabled in Parliament, and this applies to most of the ordinances that have been called constitutional terrorism.

An ordinance that affects the very electoral process, however, could result in fundamental changes. If the electoral process continues unchanged, the new local body officials will have their entire tenure to alter things, even if the Rajasthan state assembly alters the ordinance. The only opportunity now stands with the Rajasthan High Court.