"These are from before Partition," my grandfather, who was born in what is now Pakistan, told me, his fingers grazing an old gaz, a yardstick, and a ghara, a metal vessel. He told me that his father had used the gaz to measure fabric at his cloth store in Lahore and that his mother had used the ghara to churn buttermilk.

My grandfather holds the gaz from his father's Lahore cloth shop.

A mixture of tender sadness entered his voice when he described how the objects were connected to his parents and how they were among the few remaining fragments from their life in Lahore. These objects had travelled across the border, through riots, eventually finding their home in Roop Nagar in north Delhi, where my grandfather lives. It struck me then that even banal objects could lay claim to a rich past. I realised how they could become storehouses of memories.

"Before Partition," my grandfather had said. The most catastrophic event in the sub-continent's contemporary history had divided lives into two distinct periods. It was an event that had led to the displacement and death of millions. It was a massive exercise in human misery, photographer Margaret Bourke-White once said. I, too, had always thought of Partition as a vast phenomenon: large, sweeping, monumental.

But what about the individuals in this chaotic vastness, people forced to evacuate their homes? Lost in official statistics, power politics and refugee camps, we had forgotten the individual.

So months after my grandfather pulled out the gaz and the ghara, I decided to write an alternative history of the Partition, for my Master of Fine Arts thesis at Concordia University in Montréal. I wanted to study the notion of "belonging through belongings". My primary subjects of study became things that people had carried across the border in both directions, and by extension, the individuals to whom they belonged.

Such objects were, despite their apparent mundane nature, the only physical reminders of another home and of childhood. Each object's emotional weight far exceeded its physical weight. In a way, it contained the weight of the past.

Starting in 2013, with the curiosity of a collector and the tenacity of an archivist, I travelled between Delhi and Lahore, searching for such objects. Each time I sat down with someone who had crossed the border, and listened to his or her story of survival, each time I learnt about the difficult circumstances in which an object, often concealed, had arrived at its destination, I felt that I had uncovered a new dimension of Partition. To the possessions of my grandfather, I added others' belongings, ranging from household objects to quaint collectibles, as well as the memories they represented.

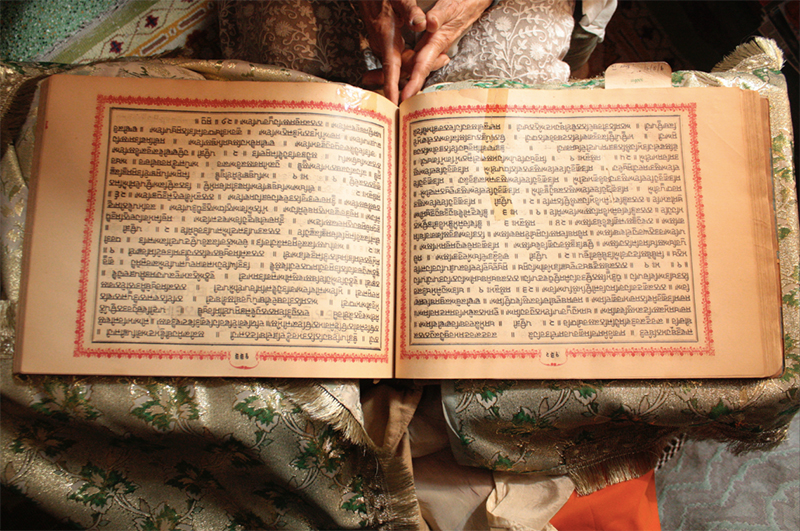

I listened to the story of a Guru Granth Sahib dating back to the early 1900s that belonged to an elegant woman in New Delhi’s Defence Colony. The family had left the holy book behind in Rawalpindi when it moved to Shimla in 1947. A neighbour from their old hometown brought it to them after Partition.

This Guru Granth Sahib travelled from Rawalpindi to Shimla.

In my own south Delhi home was a stunning mang-tikka, an ornament worn over the middle parting of a woman's hair and that dangled over the forehead. It was made from precious stones no longer found in India. Created in the North-West Frontier Province of what became Pakistan, the headpiece belonged to my paternal great-grandmother, who had brought it across the border concealed in her clothes. It had travelled from Muriali to Dera Ismail Khan, both towns in my great-grandmother's home province, to Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, and finally, to Delhi, where she presented it to her daughter, my grandmother, on her wedding day.

My grandmother wears her mother's mang-tikka from the former North-West Frontier Province in Pakistan.

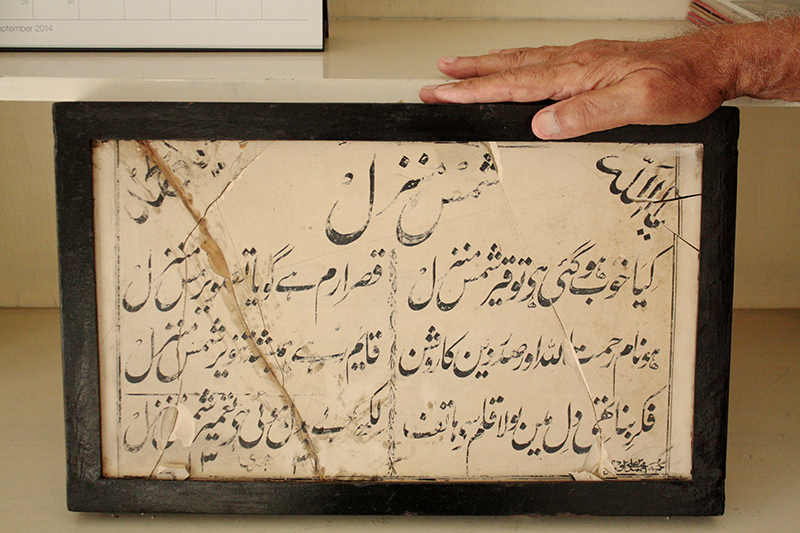

In Lahore’s Defence Housing Authority colony, I found an engraved stone slab that had once served as the nameplate of a home in Jalandhar. Years after the family that had occupied the home fled India, it made the trip across the border. A woman brought it over from India to her old uncle, who had grown up in that house, giving him the only tangible fragment of his childhood.

This nameplate from Jalandhar carries the man's family name rendered in Urdu.

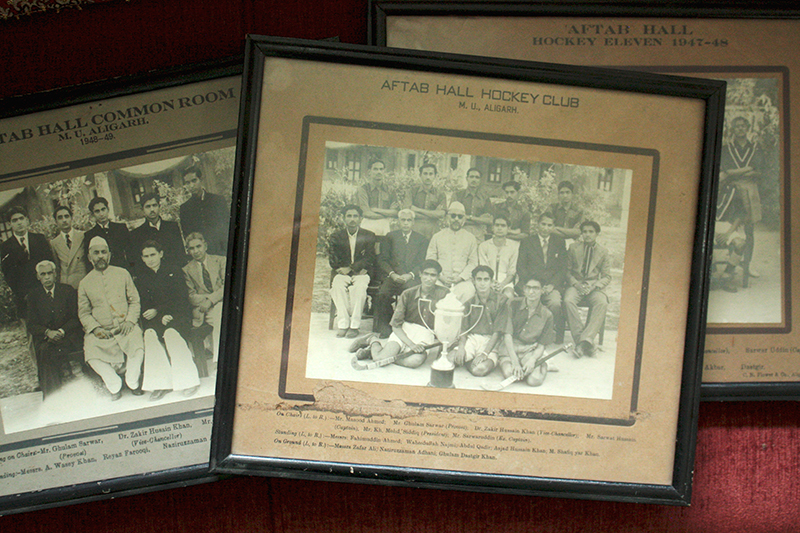

A Muslim boy from Lucknow who had been studying in Aligarh University in 1947 was the old, gentle-looking man sitting before me in Lahore, fluently recalling his days in the university hockey club and his love for the sport. Choosing to complete his education there before crossing the border in 1953, he took along on his journey from India to Pakistan neither money nor clothes but three large, framed photographs from his alma mater ‒ of him and teammates from the hockey club.

A photo of Aligarh Muslim University's hockey team in 1947.

During my research, I became obsessed with people's relationships to objects and how they subconsciously deposit parts of themselves into their belongings. Artefacts from before the Partition carry a part of the sub-continent's migratory history. They contain stories of our grandparents’ childhoods, their feelings of belonging to places and represent the comfort of home. They carry memories of a generation that will soon be gone. My ongoing project, Remnants of a Separation, attempts to collect, archive and preserve these memories.

For most people who survived Partition, talking about their experiences of that period is traumatic. They do not want to open old wounds. Yet while talking about objects from their pre-Partition days, their inhibitions often seem to fade away. People I interviewed spoke with greater ease about everyday objects from that time ‒ how the objects had survived, why those were the only ones they had chosen to take along, and what they meant to them. The objects' very mundaneness allowed people to talk in an ordinary way about their extraordinary and disturbing experiences.

Aanchal Malhotra, an artist who lives in Montréal, is pursuing an MFA, in Studio Art at Concordia University. She also works as an editor & literary agent for Red Ink Literary Agency in New Delhi.