Altogether, 45,635.63 hectares land got notified for SEZs from 2006 to 2012. Six states – Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha and West Bengal – accounted for 39,245.56 hectares of that total.

The audit reported that in these six states, 52 SEZs involving 5,402.22 hectares of land (14%) got de-notified and the land in question got diverted for other commercial purposes. The actual extent of de-notified land might be higher: as many as 46 SEZs were not produced for audit, and in case of one SEZ, an incomplete file was submitted.

Out of the 52 SEZs, 100% of the notified land was de-notified in respect of 35 developers, thereby putting a huge question mark over the logic that went into deciding the area of land acquired and the subsequent application for de-notification.

While providing all these details, the CAG performance audit report should have also given the names of the 52 SEZs where such de-notification was witnessed. This is crucially important in a policy environment where even though SEZ land acquired for “public purpose” using government machinery cannot be sold by developers, it can be used or sold by them for other “greater commercial purposes” once it has been de-notified.

The CAG cites just one example to illustrate this incidence: at Sri City SEZ in Hyderabad, it says, 228.61 hectares of the total de-notified 449.54 hectares was allotted to 18 “customers”. What’s more, the details regarding the allotment were not on record. Given such cases, the CAG office should have walked the extra mile to tell us what happened in the case of those other 51 SEZs as well.

At the least, in the illustrative case mentioned above, citizens and parliament should have been told who those 18 lucky “customers” were. Readers can start shooting applications under the Right to Information Act to seek the details that could fill in the blanks in the text of the audit report.

Idle land

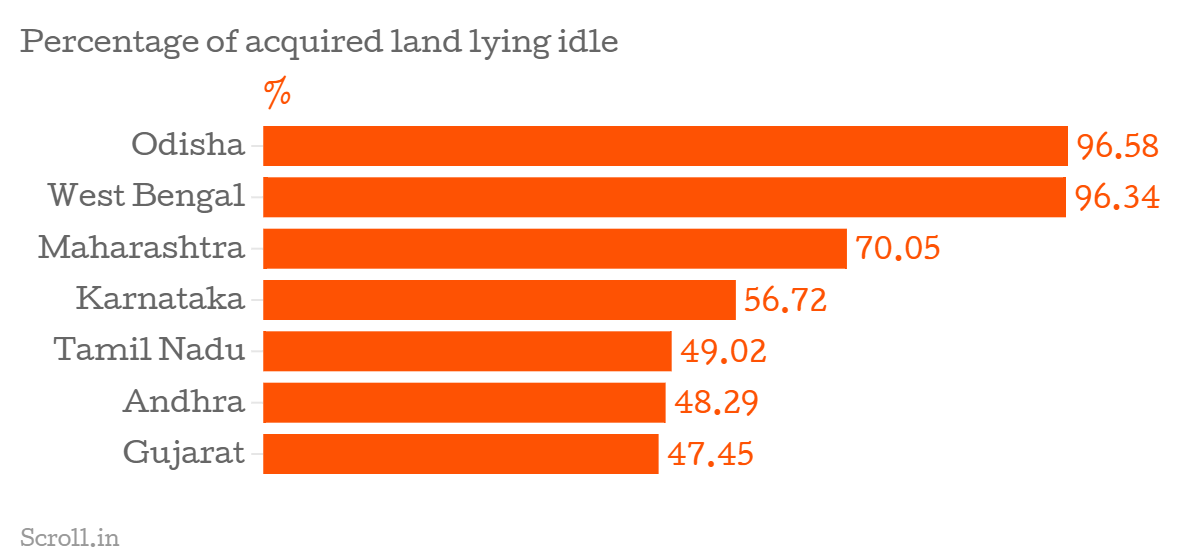

Let us now take a hard look at the extent of land notified for SEZs but which are now lying idle in seven states that account for the highest number of SEZs approved. The audit revealed that land allotted to 424 SEZs – a whopping 31,886.27 hectares – was not put to any use, even though approvals and notification in as many as 54 cases date back to the year 2006, when the SEZ Act came into being. Among these seven states, West Bengal tops the list with 96.34% of acquired land lying idle.

Out of the 54 cases that can be traced to 2006, audit scrutiny pointed out that in 30 SEZs (1,858.17 hectares) in Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha and Gujarat, the developers had not commenced any investment and the land had been lying idle in their custody for two to seven years.

The SEZ Act envisaged that a minimum of 50% of the land notified for SEZ shall be used as “processing area”, signifying the area within the SEZ to be used for manufacturing, services and infrastructure for units. CAG auditors carried out an analysis of the extent of land put to such use and found that 18 SEZs, involving a total area of 4815.19 hectares of land, could utilize only 16.29% land as processing area, leaving the rest idle.

As another example, 6,472.86 hectares of land was notified for Adani Ports in May 2009, but the developer had utilised only 833.77 hectares, leaving 5,639.09 hectares (87.11%) unutilised.

In a final masterstroke, the performance review of SEZs by the CAG underlines a moot question: “Considering the huge extent of land that had been de-notified with no economic activity for several years, the big question that remains to be answered is whether this land would be returned to original owners from whom it was purchased invoking ‘public purpose’ clause.”

Will the affected people who lost their land towards such “Sanctified Extortionist Zones” mount a threadbare analysis of this performance review and press opposition parties to ask for a thorough debate on the report’s content in Parliament during the next session?

A longer version of this article first appeared on India Together under the headline 'SEZ today, gone tomorrow'.