Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Pakistan had already generated a sense of nervous anticipation. Originally expected to come in September last year, Xi’s visit was postponed in the wake of prolonged anti-government protests in Islamabad, with the government not want anything untoward happening this time round.

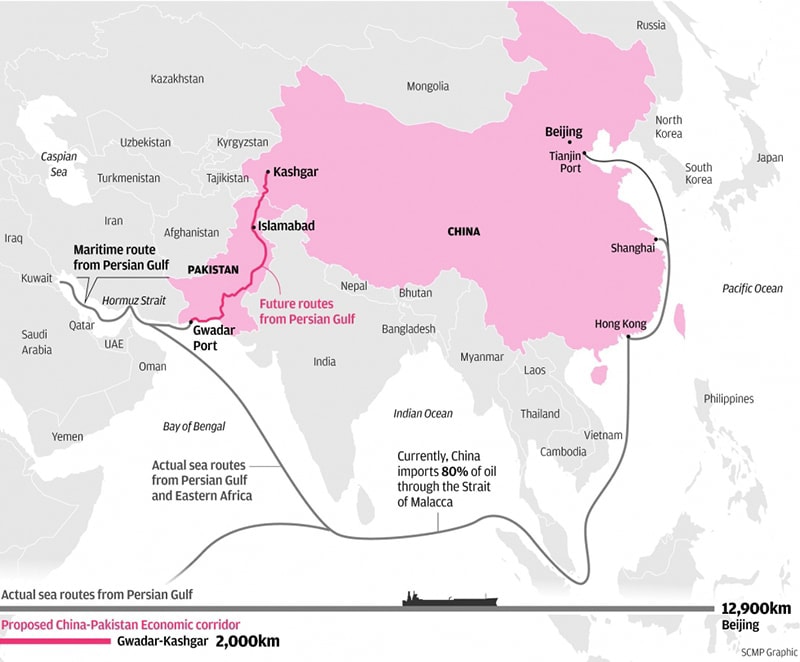

As well as signing a raft of energy, trade and investment agreements, the Chinese president also inked a pact on Balochistan’s Gwadar port, which is part of the 3,000 kilometre-long strategic China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which could radically alter the regional dynamics of trade, development and politics.

Gwadar, once a part of Oman before it was sold to Pakistan in 1958, is one of the least developed districts in Balochistan province. It sits strategically near the Persian Gulf and close to the Strait of Hormuz, through which 40% of the world’s oil passes.

The construction and operation of this multi-billion dollar deep-sea port at Gwadar was contracted to a Chinese company in 2013 and some analysts argue that the port could turn into China’s naval base in the Indian Ocean, enabling Beijing to monitor Indian and American naval activities.

Establishment of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was first proposed by Chinese premier Li Keqiang during his visit to Pakistan in May 2013. “Our two sides should focus on carrying out priority projects in connectivity, energy development and power generation,” Li said at the time.

Source: SCMP

Pakistan’s strong ties with China may mean the initiative succeeds where other regional energy projects have become mired in security problems and political disagreements, says Vaqar Zakaria, energy sector expert and managing director of environmental consultancy firm Hagler Bailley Pakistan.

“The Pak-Iran pipeline is on hold, the World Bank-backed Central Asia South Asia Electricity Transmission and Trade Project has to contend with security issues relating to the passageway through Afghanistan, and importing power from India has to wait for core issues between the two countries to resolve,” he said.

Energy-poor Pakistan certainly seems to have found a saviour in China, which has promised to stand by the country in its dark hour (parts of the country suffer power cuts for up to 18 hours a day).

So overwhelmed is President Mamnoon Hussain that he has predicted the economic corridor will be a “monument of the century” benefitting “billions of people” in the region.

Zakaria believes projects conceived under CPEC will ease Pakistan’s energy shortages and make a “substantial difference in the long term with both generation and transmission covered.”

However, coal figures prominently and Chinese money is “timely and useful” for cash-strapped Pakistan struggling to finance energy projects from western donors.

The CPEC project will include building new roads, an 1,800-kilometre railway line and a network of oil pipelines to connect Kashgar in China’s western Xinjiang region to the port of Gwadar.

The project also includes an airport at the port and a string of energy projects, special economic zones, dry ports and other infrastructure.

The estimated cost is expected to be $75 billion, out of which $45 billion will ensure that the corridor becomes operational by 2020. The remaining investment will be spent on energy generation and infrastructure development.

China’s new silk roads

While the trade and energy corridor may be ‘monumental’ for Pakistan, for China it is part of more ambitious plans to beef up the country’s global economic muscle.

Chinese officials describe the corridor as the “flagship project” of a broader policy ‒ “One Belt, One Road” ‒ which seeks to physically connect China to its markets in Asia, Europe and beyond.

This initiative includes the New Silk Road which will link China with Europe through Central Asia and the Maritime Silk Road to ensure a safe passage of China’s shipping through the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

“China is not building the corridor as an act of charity for Pakistan,” says Michael Kugelman, a senior associate at the Washington DC based Woodrow Wilson Center.

“It will happily fund and build any structure that plays into this goal – whether we’re talking about roads or ports.”

Some experts argue this initiative can bring greater cohesion in South Asia, one of the world’s least economically integrated regions.

Adil Najam, Dean of the Boston University Pardee School of Global Studies, believes anything that binds the region together is “a good idea” since countries tend to focus on “zero-sum geostrategic posturing” rather than recognising the benefits of integration.

India, US worried

At the same time, the new silk roads are bound to intensify ongoing competition between India and China – and to a lesser extent between China and the US – to invest in and cultivate influence in the broader Central Asian region, says Kugelman.

“India has long had its eyes on energy assets in Central Asia and Afghanistan, even as China has gobbled many of these up in recent years. The US has announced its own Silk Road initiative in the broader region,” he said.

India is concerned about China’s growing investment in Pakistan, particularly its recent decision to fund a new batch of nuclear reactors. Pakistan plans to add four new nuclear plants by 2023, funded by China, with four more reactors in the pipeline (adding up to a total power capacity of 7,930 MW by 2030).

Many argue that China is supplying nuclear technology to Pakistan in defiance of the Nuclear Suppliers Group guidelines, which forbid nuclear transfer to Pakistan as it has not signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. China argues that these projects were agreed with Pakistan before it became a member of NSG in 2004.

Conflict in Balochistan

However, the economic corridor is unlikely to be successful unless there is peace in Gwadar, a district embroiled in conflict. Militant groups opposed to foreign-funded investments are active in the region, with some of them also having attacked Chinese engineers working on the port.

This is one reason given by experts for the change of route to pass mostly through Punjab, thereby avoiding some of the country’s most strife-torn areas in the provinces of Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and much to the chagrin of local legislators.

At the same time, China has concerns about the growing influence of radical religious groups in Pakistan in its own province of Xinjiang, which has a significant majority of Uighur Muslims.

For now, the Pakistani military plans to train over 12,000 security personnel and form a “special division” to provide security to Chinese personnel working on the economic corridor.

Some 8,000 security personnel have already been set out to protect over 8,100 Chinese personnel working on 210 projects across Pakistan.

This article was originally published on Dawn.com.