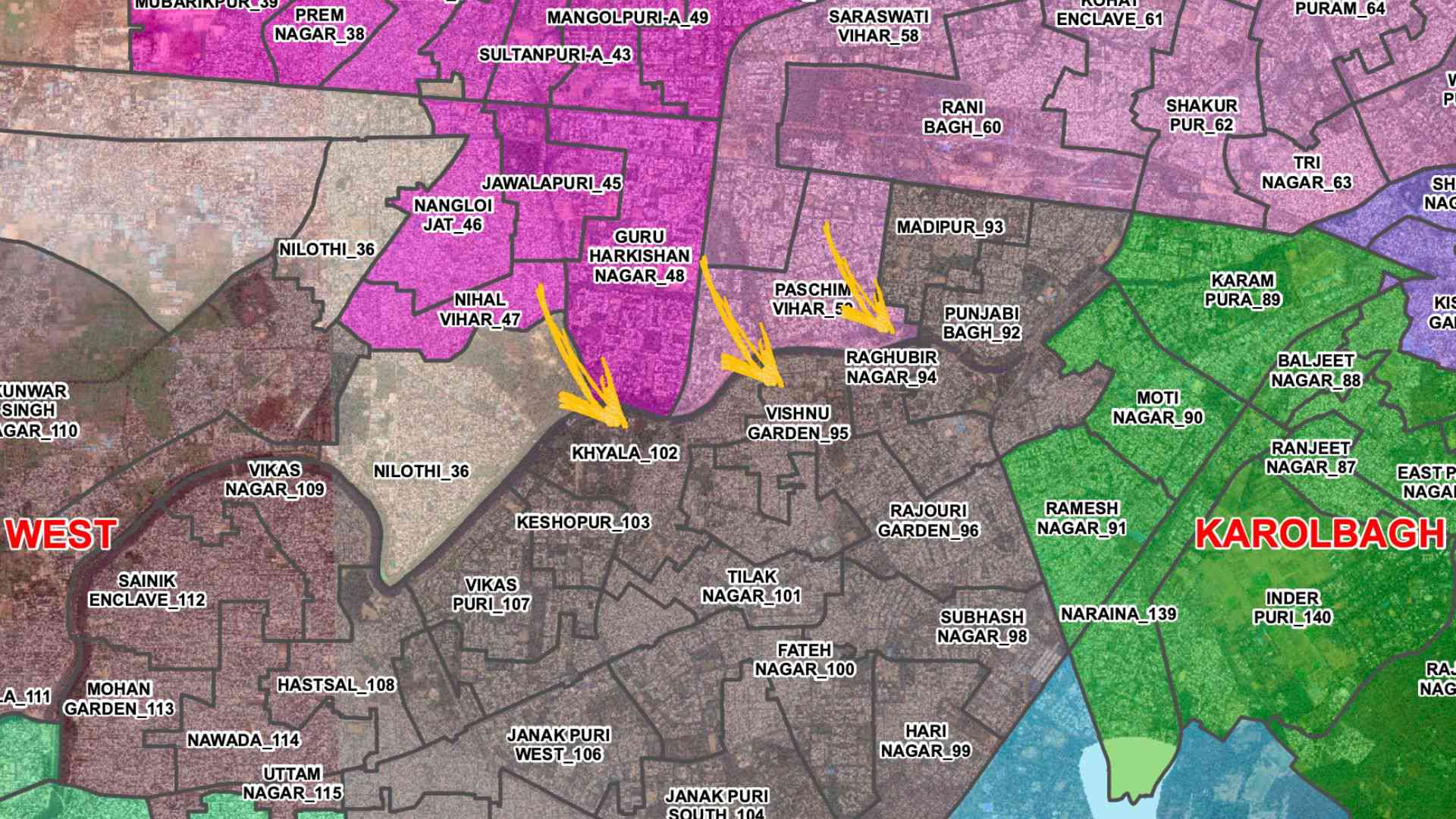

For over two decades, the jeans stitching hub in the urban village of Khyala in West Delhi drew hundreds of Muslim tailors from Uttar Pradesh. Scores of sweatshops mushroomed here as the business grew, prompting the authorities in 2021 to recognise Khyala as an industrial area.

In time, a wholesale jeans market – among the largest in Delhi – sprang up in the neighbourhoods abutting Khyala. While Muslims dominated the business by virtue of being the first movers, Hindus and Sikhs found space in it too.

All was well, locals say, till accusations began to float around this summer that Muslims were waging a so-called jeans jihad.

According to this conspiracy theory, Muslims had been using the jeans business to change the demography of the area by forcing out Sikhs and Hindus.

Amplifying the claims (though he did not specifically use the term “jeans jihad”) was Manjinder Singh Sirsa of the Bharatiya Janata Party – the local MLA and Delhi’s minister for industries.

On social media, he has weaponised residents’ grievances against the haphazard expansion of the jeans industry using communal rhetoric that attacks its mostly Muslim workers.

Sirsa has repeatedly asserted that the Muslims from Uttar Pradesh working in the jeans business are “Bangladeshi and Rohingya infiltrators”. Not only that, craftsmen alleged that the minister has used his powers to shut down jeans factories and drive workers away from the area.

When Scroll visited Khyala, it was clear that industrial activity had been virtually paralysed because of a sealing drive against establishments claimed to be illegal. The few workers still around were idling about. Most had returned to Uttar Pradesh or moved elsewhere for work.

The industries minister has publicly claimed credit for the shutdown of the Khyala garment hub.

The Rohingya-Bangladeshi bogey

“You can come to my area and see for yourself,” the minister boasted on a podcast that was aired on July 7. “I chased out many of them who were working in jeans factories.”

The interviewer had asked Sirsa what the BJP government in Delhi was doing about “illegal immigrants” from Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Sirsa offered no evidence to support his allegations. There are no reports of the police investigating claims of foreign migrants working in Khyala, much less confirmed instances.

The station house officer of Khyala police station refused to comment on whether any foreign nationals had been found in the area. Calls and messages to the deputy commissioner of police in West Delhi district went unanswered.

When Scroll asked Sirsa about the absence of evidence for his Rohingya-Bangladeshi claims, he said: “It is good if they have run away. Now our area will be safer.”

Sirsa also said that he was “executing orders” passed by the Supreme Court regarding unlawful businesses. “The problem of illegal factories has been there for a long time,” he added. “We are sorting it out now.”

The podcast was not the first time that the minister had claimed that Bangladeshis and Rohingyas were employed in the Khyala jeans industry. His social media posts show that he began using the communal dog whistle back in May.

In the beginning, Sirsa only spoke against the factories that had expanded into the residential parts of his constituency. There was some merit to this complaint, said residents.

Khyala is chock-a-block with factories, offices and dhabas. As business grew, establishments started to spill out into the neighbouring areas of Raghubir Nagar and Vishnu Garden.

This had a dual effect on those already living there: while real-estate prices shot up, traffic and waste management got worse.

“During the elections, Sirsa promised to clear the roads and drains,” said Shrikant Porwal, a jeans wholesaler and a prominent member of the market association. “He was under pressure to perform. If he did not solve problems in his own constituency, it would reflect poorly on him as a minister.”

By the end of May, Sirsa was accusing business owners of making the area uninhabitable and threatening them with imminent action. In one of his videos, he singled out a biryani shop for attention. “You people have made it impossible for residents to survive here,” he said. “Sisters, daughters and mothers can’t step out of their homes.”

A sealing drive began in June, with government officials downing the shutters of allegedly illegal factories. Around the same time, sections of the Hindi media picked up the story and labelled it it a case of “jeans jihad”. According to these publications, Hindu and Sikh residents were being forced to vacate the area because of the ever-expanding, Muslim-dominated denim business.

Curiously, most of these media outlets used images of the same placard that was supposedly pasted outside buildings in Khyala. “Jeans Jihad. This house is for sale,” it read. None of the people that Scroll spoke to for this article knew where the placard came from.

On July 1, Sirsa joined the chorus.

“Hindu girls and Sikh families are suffering in my constituency,” he claimed in an Instagram video. “You [Muslim business owners] opened chicken shops there to drive people out. They had to move out of their homes.”

Sirsa told Scroll he had nothing to do with the “jeans jihad” theory. However, he reiterated his concern for Hindu and Sikh families. “If Rohingyas and Bangladeshis come here, who else will be at risk?” he asked.

Residents insist that this fear-mongering is without basis and precedent. Abid Khan, who has made jeans in the area since 1999, said that Sikh residents had never complained about their Muslim neighbours in Khyala and Vishnu Garden before.

“I challenge you to go through police records and find five such cases from the last 20 years,” he added. “Have the Sikhs suddenly discovered these problems with us Muslims? There is no issue between the two communities. Only outsiders are bringing this up.”

Harcharan Singh Kalsi, a 55-year-old Sikh salesman, also said that residents like him bore no ill feeling towards those working in the jeans business. In fact, he credited the industry for pushing up property prices in the area.

“In Delhi, there are many neighbourhoods like Chandni Chowk and Sadar Bazaar that are both commercial and residential,” he said. “It is a good thing. We have no problems with it.”

A senior police officer from West Delhi district, who asked not to be identified, dismissed the idea that the jeans industry had led to more crime in the area. Disputes between neighbours had led to the civic authorities sealing some factories but there was no increase in street crimes, the officer said.

However, Sirsa stuck to his guns and reiterated the Bangladeshi-Rohingya charge in his attacks on the jeans business. “These people are dangerous like snakes,” he said in the podcast. “They bite the hand that feeds them.”

Gripped by fear

The minister’s words and actions have had a devastating impact on those who depend on the jeans business for their livelihood. Until the start of the government crackdown in June, it used to employ more than 15,000 workers, estimated Abid Khan, the jeans manufacturer. Only a fraction of them are still around.

“There is fear in the minds of people,” said Khan. “The poor, daily wage earners have been hit the worst. Those who did not have licences simply picked up their machines and left.”

Shah Rukh Khan, a tailor from Kasganj in Uttar Pradesh worked in Khyala for 15 years before the sealing drive forced him to go back. While he still stitches jeans for a living, his earnings have dropped substantially.

“I go to Delhi to buy supplies so that is an extra cost I have to bear,” he said. “There is no place like Delhi for this business. I had to leave because my landlord was afraid that his property would get sealed.”

Workers who stayed behind had to reckon with frequent shutdowns and lost wages because of the frequent visits from government officials. When Scroll visited Khyala, workers were roaming the streets and chatting about which factories were sealed that day.

“I will have to go and find work in Noida now,” complained Shanu Khan, a tailor from Budaun in Uttar Pradesh. “There are many problems here. All the dhabas have shut down.”

Aman Pathan, another tailor from Budaun, said that officials had carried out inspects three times in just the previous week, effectively bringing work to a halt. This meant that he and other workers had managed to make very little money in this time because their pay is based on how many pairs of jeans they are able to stitch every week.

Asked about the charge that the workers were Bangladeshis and Rohingyas, Pathan simply said: “They can call us anything they want to, they are in power.”

Even Sirsa’s supporters in Khyala and Vishnu Garden struggled to defend his claims about foreigners working in the factories.

“I have never seen any Bengalis working in this market, let alone any Bangladeshis or Rohingyas,” said Porwal, the member of the market association. “People from Uttar Pradesh run the show here. Sirsa may have been talking about the whole constituency and not this market.”

While Porwal expressed support for government intervention in his area, he did not agree with “jeans jihad” theory.

“Things should be resolved peacefully,” he appealed. “So many people depend on this market. Yes, all businesses should be legal. But nobody should have to leave. After all, every market in Delhi is somewhat illegal.”