On June 19, more than 3,000 factory workers employed by Orient Craft, one of India’s top garment manufacturers and exporters, rioted at the company’s plant in Gurgaon, Haryana. They set fire to a fabric store inside the plant, overturned vehicles around it and set them alight.

A rumour had got around that four workers had been electrocuted in a lift in the plant that morning. It later turned out that 27-year-old Pawan Kumar, whose job is to attach price-tags to garments, had received an electric shock but had not died. Hundreds of policemen had to keep guard at the factory for the next few days before the Rs 1,500-crore company could resume production.

It was the third workers’ riot in Orient Craft in three years, and the second instance of labour unrest in Delhi and Haryana in the last three months.

On February 12, workers from several factories in Udyog Vihar on the Delhi-Haryana border went on the rampage after a rumour spread that Sammi Chand, a contracted quality checker at the leading export firm Richa Garments, had died after being beaten by the company’s security guards. Over a thousand workers turned to violence, setting fire to cars and burning documents in the plant.

Two years ago, workers in Okhla Industrial Area in Delhi had damaged 15 factory buildings on the final day of a countrywide strike called by central trade unions. A young worker in Okhla who took part in the 2013 violence recounted what he had seen: “There were several luxury cars parked outside factories. Workers ran from factory to factory, pelting stones, overturning cars, shouting, ‘yeh car kachre ka dibba hain, jala do inhe’" ‒ these cars are waste bins, burn them.

The regular flare-ups suggest rising discontent among workers. Trade union leaders say workers’ dissatisfaction is not finding an outlet in non-violent agitation, or strikes, as both government and factories discourage the formation of trade unions and, by extension, collective bargaining.

Against this background of violence, the number of strikes has gone down sharply. Since 2010, labour department officials have not recorded any strikes in industrial areas in Delhi. All over India too, strikes in factories have declined in the last decade. The 1970s witnessed almost 100,000 strikes each year. But as per Labour Bureau reports, there were only 240 strikes in 2008, 167 in 2009, 199 in 2010 and 179 in 2011.

Drop in strikes across India over the years

The decline in strikes has occurred while the number of workers hired on temporary basis on contracts has risen. Labour historian Prabhu Mohapatra calculates that while in the 1980s only 7% of the workers in the manufacturing sector in India were on temporary contracts instead of being permanent employees, this had risen to 35% by 2012. Over 84% of workers in the unorganised or informal sector are contract, casual or temporary workers, with no job security or social security. The National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector estimates that even in the formal sector, over half the workers are in the "informal’ category", with no secured tenure of employment.

Contract workers in registered manufacturing

Contract workers in Okhla, Gurgaon, Manesar are hired for lower wages than permanent workers. They have no job stability or social protection. In fact, adjusting for inflation, in real terms, workers earn less today than they did in 1990.

In this changing landscape of labour unrest, the government has proposed changes to the legal framework that will further limit the scope for formal collective bargaining and non-violent agitations.

Legal changes

In April, the National Democratic Alliance government proposed integrating three labour laws – the Trade Unions Act 1926, the Industrial Disputes Act 1947 and the Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Act 1946 – into a single code for industrial relations.

The draft code significantly alters how trade unions can be formed in factories and registered with the government. Currently, seven members of a union can apply for registration irrespective of the establishment’s size. The draft bill proposes that at least 10% of the total employees or 100 workers be needed to form a trade union.

It modifies the definition of a strike to include “casual leave on a given day by the 50% or more workers employed in an industry”.

Trade unions across India see a grave threat in these changes. They say the new law will make it difficult for workers to form unions and will undermine workers’ right for collective bargaining.

Tapan Sen, a Rajya Sabha member and vice president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, said that by enforcing a law that restricts workers’ participation in unions, the government is taking away all their outlets for grievances, pushing them towards more militancy. “If you push someone against the wall, what will they do?" asked Sen. "They will hit back at you.”

Eleven central trade unions have declared a nationwide strike on September 2 to protest against the government’s proposed changes in labour laws. The last time they had declared a strike was on February 20-21, 2013 – when the Okhla violence occurred.

Low levels of unionisation

While there is outrage over the legal changes, on the ground, the reach and strength of trade unions is already fragmented and weak.

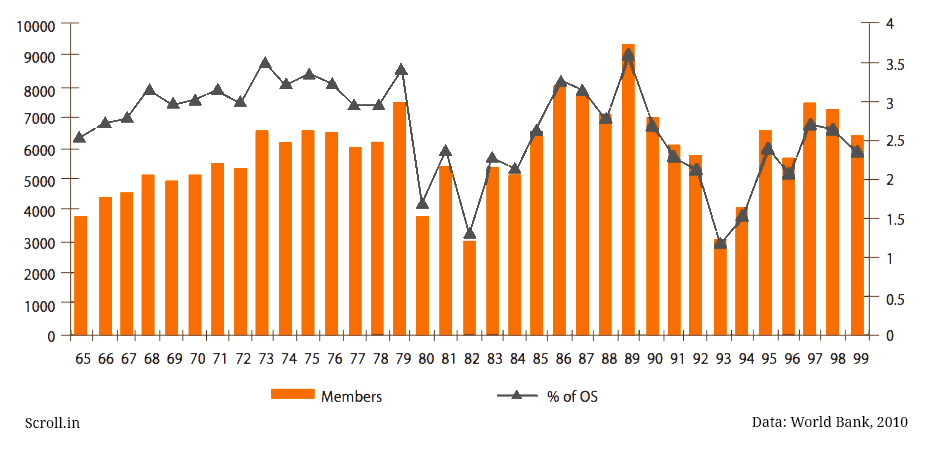

Data show members in registered unions is low and has declined over time, though there are sharp fluctuations. Only 8.6% of the workers surveyed for the National Sample Survey of 2000 were members of trade unions or associations, according to a 2010 World Bank study. The figure varied widely from state to state: it was 22% in Kerala and only 5.7% in Madhya Pradesh. Even put together all 11 central unions' members constitute only 15% of India's workforce, and are concentrated in the public and formal sectors.

Official trade union membership numbers and rates over various years

Many challenges

In several states, unions and workers' groups say organising workers or registering unions is already quite difficult.

The Indian Federation of Trade Unions, which was set up in 1979, has presence in several states. At its South Delhi office, just 2 kilometres from the Okhla Industrial Area, Animesh Das, a doctor and president of the Delhi union, said reaching out to workers is getting harder.

“It is a huge challenge,” said Das. “At the gate of the factories, no worker can even stop and talk."

Fifty metres from Das’s office is the south district office of the Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh, the trade union wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh. Its district secretary KB Singh said that the majority of workers from Okhla and nearby industrial areas worked on contract and rarely approached the union. They fear for the repercussions on their jobs if they joined the union, he said.

Das said that in 2005, the Indian Federation of Trade Unions surveyed 293 factories – 149 in Okhla and 144 in Mayapuri industrial area in north Delhi. Less than one-tenth of the workers were being paid minimum wages or had access to provident fund and health benefits. And yet, the rates of unionisation were lower than the national average. In Delhi, of the over 10 lakh workers in the unorganised sector or working in the organised sector as casual workers, not even 1% were members of trade unions, he estimated.

Even in the few instances where workers organised themselves, they found registering unions an uphill task. Das said that officials often deny registration to unions hinted as an unwritten norm.

“Five years back, we were trying to organise workers in Denso, a German MNC that manufactures automobile parts,” said Das. "The labour officials in Ghaziabad in UP repeatedly asked for more documents and made us run in circles. Finally, we approached the Labour Commissioner in Kanpur. He told us flatly: you can form an internal, company union, but the government will not register the union.”

An “internal” or “company union” would mean no honorary members, such as labour law experts or trade unionists like Das would be allowed in the union, currently permitted under the Trade Union Act of 1926.

Another significant proposal

This last -mentioned feature is among the provisions of the Act that the NDA government plans to change. While under the Trade Unions Act, honorary members not employed directly in an industry could constitute 50% of the union's members, the new bill proposes only employees be allowed to form unions. In the unorganised sector, it permits two honorary members in a union.

Das added: “Workers often know of some rights but not what the gaps and nuances in the law are. Therefore, when the management sends Human Resources experts to talk to workers, it can become an unequal negotiation.”

In Haryana, workers' representatives said companies were cracking down on even internal, plant-level unions. Representatives of the newly formed Workers' Solidarity Center said in the previous year, several attempts by workers to form unions were thwarted, with labour officials returning applications repeatedly, turning them down as invalid.

Amit, a member of the Workers’ Solidarity Center, spoke of recent events in Haryana’s Bawal industrial area, which lies on the proposed Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor. “Every time workers submit their names and details in applications for a union, the management transfers those workers to another division, or in some instances, simply fires them,” he said. “One company filed a case in court against the workers, alleging they had tried to get signatures of others by force.”

In Uttarakhand, several groups of workers went on strikes in Selaqui, said Shankar Gopalkrishnan, who organises workers as part of the Chetna Andolan. Selaqui, near Dehradun, is one of the new industrial areas developed by State Industrial Development Corporation of Uttarakhand after the state was formed in 2000. He said the strikes were not reported or recorded by government officials – first, because the state recorded strikes only when the employer reported them, and second, because of growing contractualisation.

“All workers in an electronics factory here went on strike,” said Gopalkrishnan. “The employer immediately dismissed them immediately since they were contract workers. Similarly, in a pharmaceutical company, all 100 workers on strike were dismissed in a day.”

Since contract workers have to change jobs frequently, said Gopalkrishnan, his group has rewired its strategy to organize daily wage workers and workers at construction-sites.

Finding new strategies

Rakhi Sehgal, the vice president of the Hero Honda Theka Mazdoor Sangathan and executive council member of the New Trade Union Initiative said unions would have to seek innovative ways of organising. "Currently, unions do not do enough of community organising and synergising it with trade union organising," she said. "We also have to strategise to respond to what's going on the ground with respect to subcontracting, and in informal sectors of industry."

For now, squeezed by government neglect workers and frantic pace of production, workers’ resistance has become unpredictable. As the riots in Delhi and nearby states show, their discontent holds the potential to cause wider disruptions.

In Okhla, a young garment factory worker said he thought there were advantages to not having any unions. “Two years back, during a negotiation for better wage by our internal sangathan [informal association], our manager would tell us, ‘let one person amongst you talk, let one leader negotiate’,” he said. “We told him, we have none – talk to all of us.”

This is the final part of a series on labour law changes. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.