The release of the latest Socio-Economic Caste Census data only gives further credence to this, with two maps in particular illustrating just how cut off rural households can be.

Consider India's great telecom boom. This was supposed to be the country where smartphones spread faster than computers: you might not have a pukka house, it was thought, but you would certainly have a phone that can take selfies. The 2000s were supposed to be the years that phone coverage become universal. But that's not quite true.

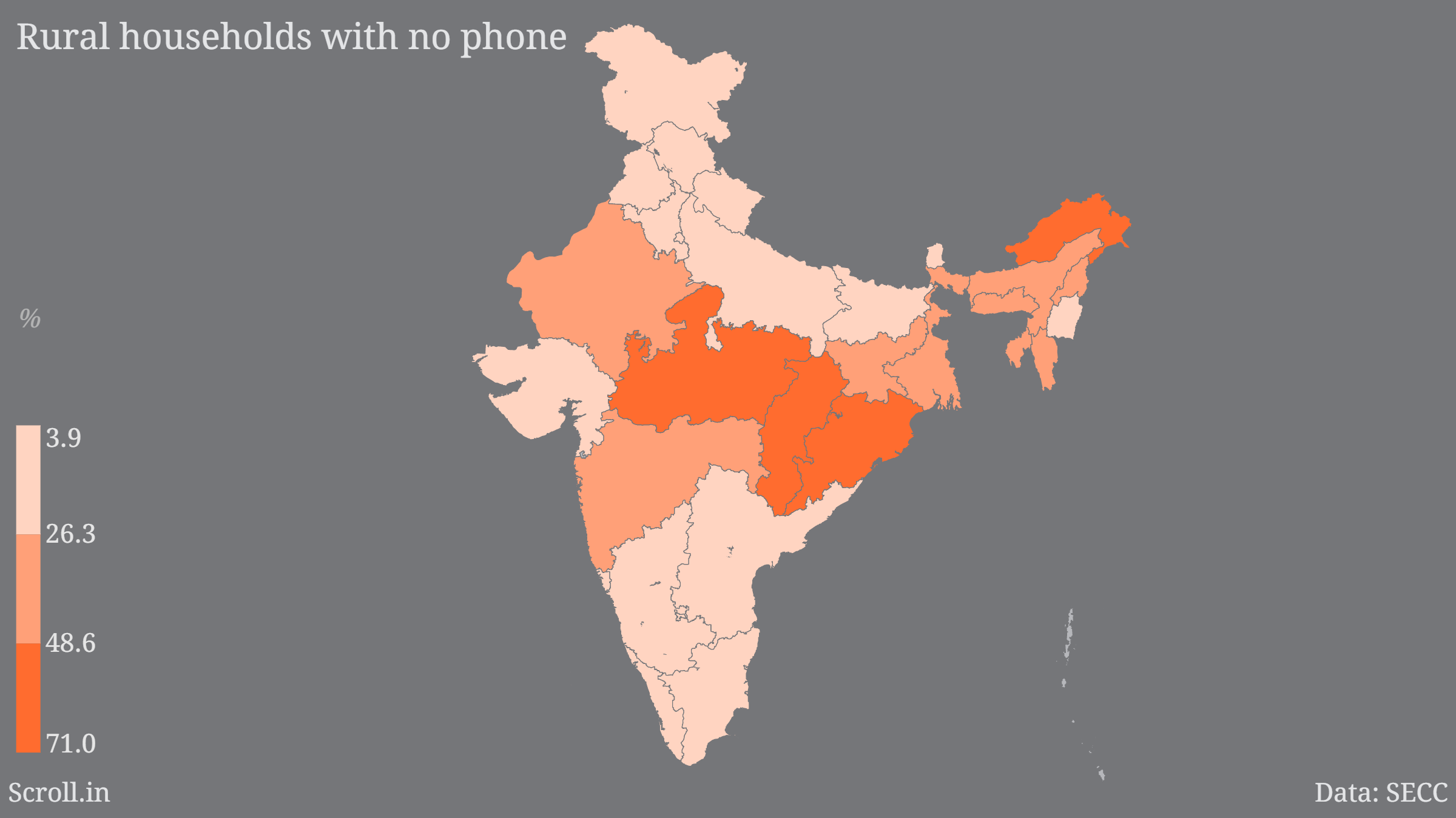

The SECC data include details about rural households with mobile phones and landlines, and they also cover those homes that have neither. The map above illustrates just how many people in rural India you still can't directly get in touch with.

Chhattisgarh and Odisha take the top spots with scandalous numbers. More than 65% of rural households in both of the states have neither landlines nor mobile phones. Arunachal Pradesh comes in third, with 49%. The numbers are relatively better elsewhere, although there is an entire rural belt through the centre of the country, including Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, West Bengal and the North Eastern states where more than a quarter of the households are still not connected by phone.

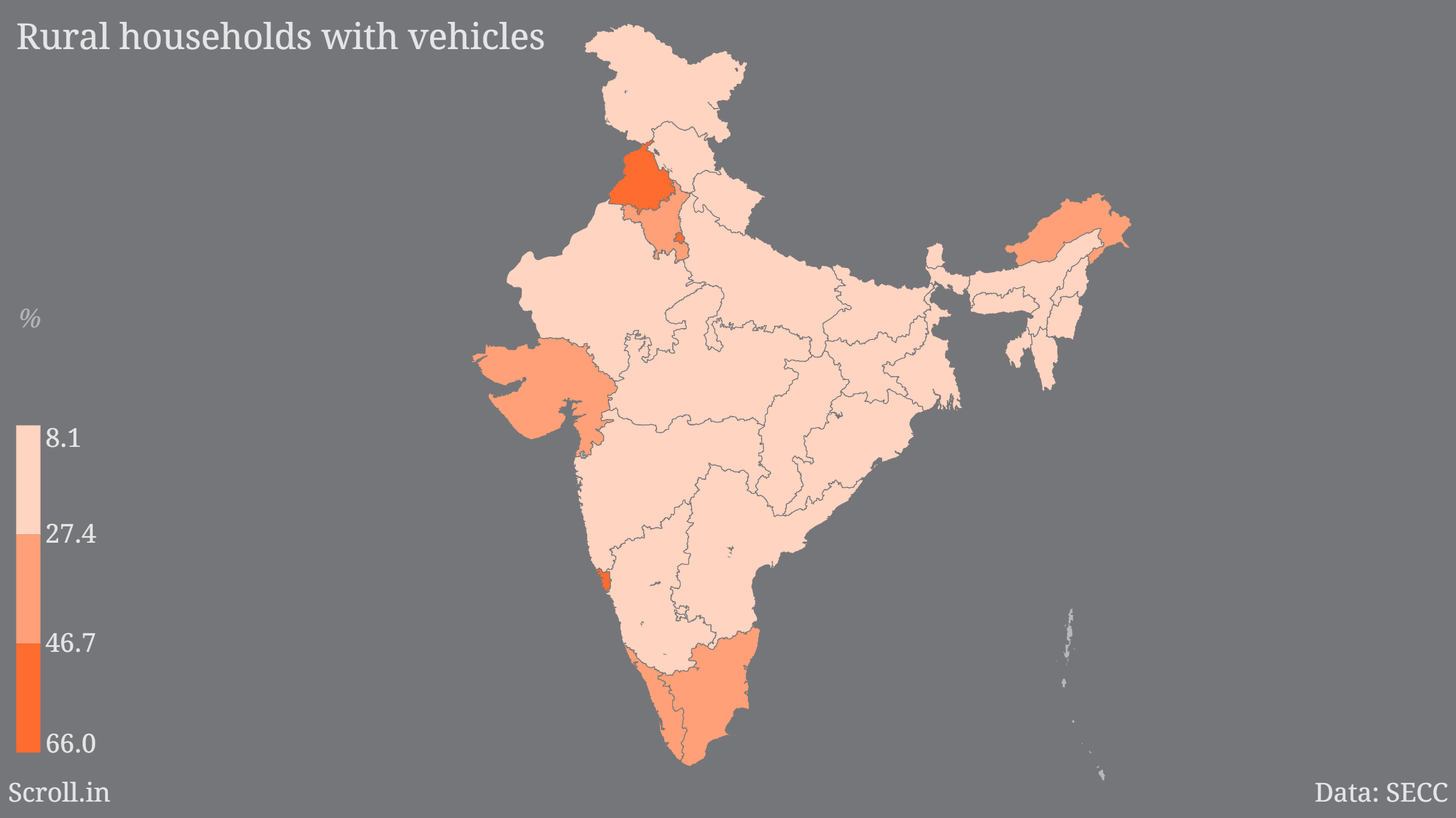

The survey also looked at asset ownership that could suggest mobility of the direct kind. It estimated the percentage of rural households owning a vehicle, whether two-, three- or four-wheeled or even a motorised boat, that would require registration.

Only two states, Punjab and Goa (as well as the National Capital Territory of Delhi), have more than half the rural households owning one registered vehicle. The vast majority of states came in the 8-27% range, suggesting that under a quarter of rural households own one vehicle. Again, Odisha and Chhattisgarh came in close to the bottom, with less than 10% of rural households owning a vehicle.

Again, this may not necessarily seem like a big deal to city dwellers who are used to reasonably reliable and frequent public transport. But for rural households, relying on the state to provide transportation options is much more of a gamble, considering in some places even the local state road transport corporations have shut down because of inefficiencies, forcing residents to rely on private operators.

For all the derision the India-Bharat divide may have received in recent times, the fact remains, life in those two imagined countries is simply not the same.