A narrow path in the wilderness off the Temple Road in Mcleodganj leads to Jampling Elders’ Home run by the Central Tibetan Administration. Here, flipping through the pages of a national daily, sits 66-year old Bhuchung Tsering. As a news item commemorating the 1965 war heroes catches his eye, his mind immediately trails off to another war that he and scores of other Tibetans had fought for India.

Tsering was part of the secret Special Frontier Force – also known as Establishment 22 or “Tutu Army” (Tutu is the colloquial term for Two, Two). The force comprised solely of Tibetan foot-soldiers – which the Indian government raised and used, most notably, in the 1971 Bangladesh war. However, decades later, thousands of SFF ex-servicemen are living in abject poverty, still waiting for their dues.

Born in U-Tsang province of Tibet in 1950, Tsering left for India with His Holiness Dalai Lama at the age of nine. In April 1970, while he was still finishing school, he enrolled in Tutu. “It was almost like an unsaid compulsion then. Most young Tibetans about to complete schooling were expected to enrol,” he recalled.

Soon after his training finished, the 1971 war broke out. Almost immediately, he was flown out of the SFF headquarters in Chakrata in Uttarakhand to Sarsawa in Uttar Pradesh. From there, the Tutu soldiers moved to Guwahati, from where, convoys carried Tsering and his companions to Lunglei in Mizoram. “We then sneaked into Bangladesh, towards the Burma border in North.”

The images from that war are all too vivid. Tsering lost a number of school fellows; many others were injured critically.

His own health started deteriorating some years later. Initial treatment continued at the military hospital. However, after six years of service, he was discharged from Tutu in 1976 – for further medical treatment of “pulmonary tuberculosis”, his discharge papers read.

At the time of his retirement, all Tsering received was Rs 850 – the money that had accumulated in his Service Savings Deposit fund, similar to Provident Fund for Indian employees. “There were no benefits, no pension. Whatever I received was mostly spent over the next two-and-a-half years on my treatment at the civil hospital in Dehradun.”

Tsering never married. With not much of an education, no skill developments training imparted by Tutu and failing health, he could neither find a job nor a companion – a common story of most Tutu ex-servicemen.

Penniless, he now lives in the Jampling old age home with at least 34 other ex-servicemen, many of whom participated in 1971.

The SFF Story

The Special Frontier Force, codenamed Establishment 22, was set up by the Indian government in November 1962 after the Indo-China war. Its headquarters were based in Chakrata, Dehradun and Major General Uban Singh became its first chief. Though SFF was never part of the Indian Army, its seniormost officer would always be an army officer on deputation to SFF as an Inspector General, veteran Tibetologist Claude Arpi told Scroll.

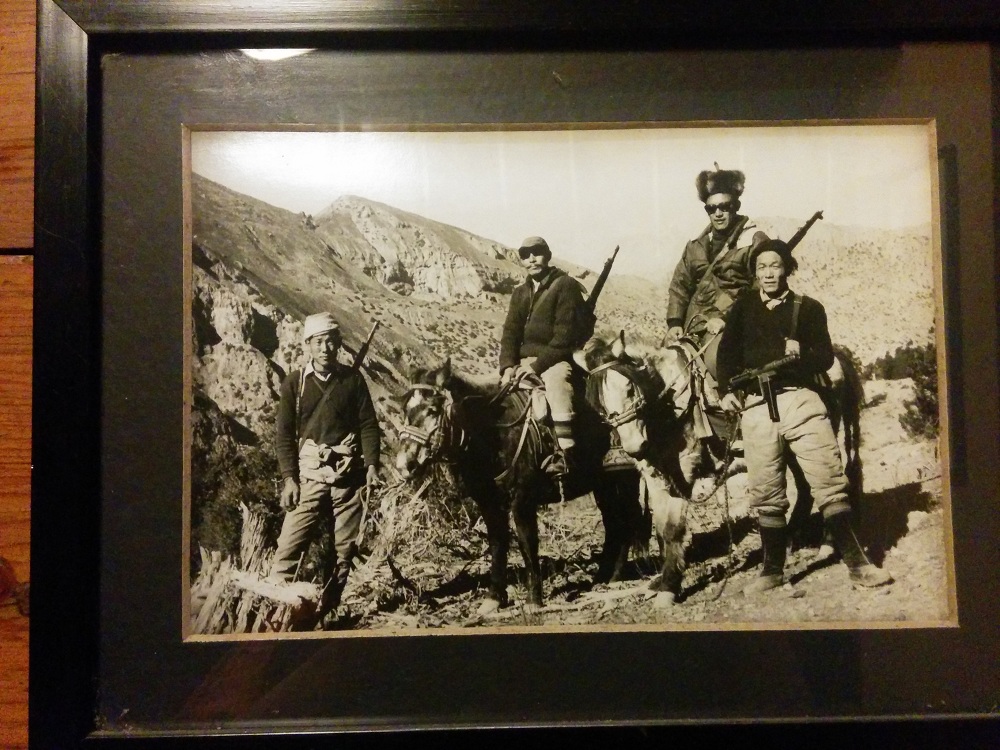

Initially, former Chushi Gangdruk fighters were recruited in SFF. These were traders, students and monks who had organised themselves as a guerrilla force in Tibet in 1956 and were instrumental in staging Dalai Lama’s escape to India. After Chinese government’s heavy crackdown, they all had fled to India.

Subsequently, young Tibetans began to be recruited in heavy numbers. Dalai Lama’s younger brother, Tenzin Chogyal aka Ngari Rinpoche was also one of the officers in 22.

According to UK-based professor Tsering Shakya, at one time, every Tibetan finishing high school in India, particularly those who failed class 10 and were unable to gain admission in college, had to join and go for compulsory military training. “In the past, every Tibetan household in the refugee settlement had at least one member serving in 22. Since late 1980s, this has declined. But if you look at the Tibetan refugee settlements in Ladakh and Arunachal, you will still find almost all households have atleast one member serving in 22,” he wrote in an email.

According to filmmaker Tenzing Sonam, the CIA and Indian Intelligence agencies started giving weapons, training and funds to the Tibetan rebels for setting up both the 2000-strong Mustang Resistance Force in Nepal and the SFF in India.

Sonam’s father Lhamo Tsering was then the chief liaison officer between CIA and Tibetan rebels for Mustang. He recalled how a tripartite office was set up in Delhi with a representative each of CIA, Indian Intelligence and Tibetan rebels. “Tibetans were better suited for mountainfare, had the language advantage and could be useful against Chinese in case the need arose. That’s how Tutu army was formed.”

“When CIA withdrew its aid to the Tibetan establishment in Mustang, some of those soldiers from Mustang were also recruited in 22,” Shakya added.

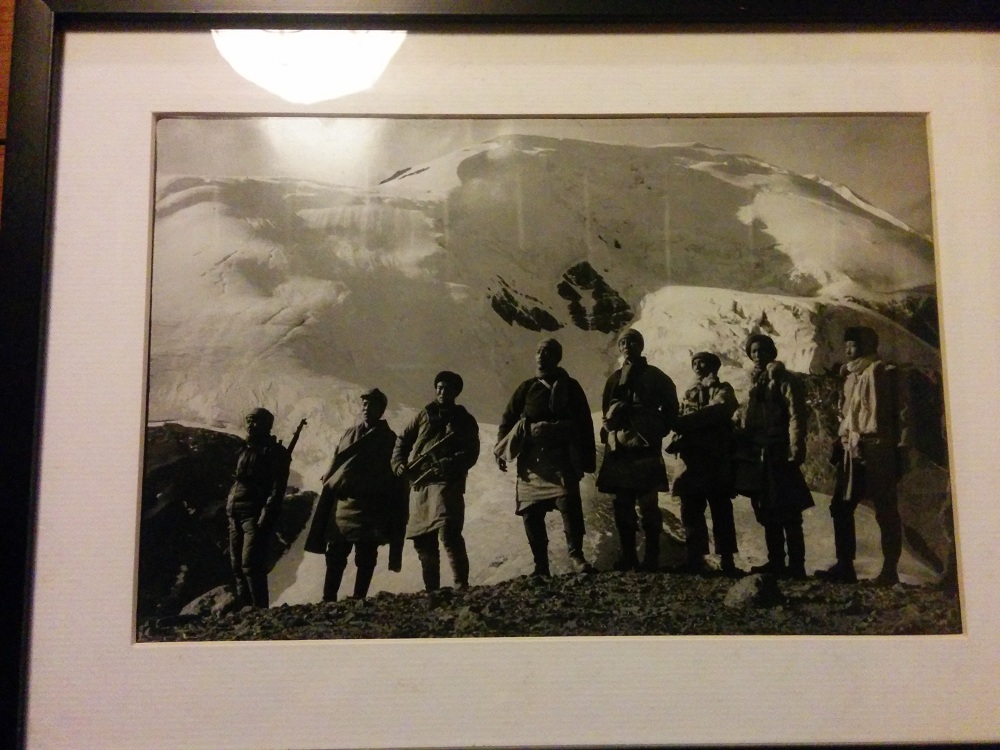

Senior journalist Dilip Bobb, who broke the SFF story in India Today magazine in late 1970s, told Scroll that the main aim was to “create unrest inside Tibet” and spy on China’s nuclear plan. “SFF soldiers were part of a covert operation led by an Indian Army colonel under the garb of mountaineering expedition to install listening devices on high altitude. They were specifically trained in parachute jumping, high altitude warfare and surveillance. The Aviation Research Centre was set up under R&AW [Research and Analysis Wing] to aid SFF get airborne. The idea was to airdrop them into Tibet.”

A highly placed former R&AW officer said, on condition of anonymity that another reason for setting up SFF was that a number of armed rebels were “floating around” in India and “could have become a problem”.

“They were extremely unruly; a law into themselves. So, it was decided to keep them in a camp and pay some money,” the R&AW officer said.

The war and unending wait for dues

According to members of the Ex- Tibetan Servicemen Association in Dharamshala, nearly 3000 SFF soldiers participated in the Bangladesh war. Those still alive recollect the same route like a photographic memory: they were summoned back to Chakrata from their postings, flown to Sarsawa Air Force station, taken to Assam from where they branched out to Lunglei and Demagiri in Mizoram and finally into Bangladesh.

“Many of these were monks. Almost 58 soldiers died and 250 received cash awards depending on injuries and citations,” President Tashi Bhuchung said.

There, however, was no official recognition – no chakras, no medal. Moreover, the ones who had actually helped India fight and win such an important war were also among the majority who never got any monetary benefits.

The initial terms of employment for SFF were very hazy.

Till 1985, retiring soldiers got no monetary benefits. Interestingly, a large number of those who participated in Bangladesh war fell in this group. 1985 onwards, SFF began giving lumpsome amounts to those retiring. These were actually small amounts, mainly comprising of the soldiers’ own savings and gratuity. According to official records available with Tsering Dhondup, who joined Tutu in December 1962 and is one of earliest soldiers alive, almost 4500 soldiers retired before 1985 and around 2000 in 1985-2008.

From 2009, the SFF soldiers started getting pensions. However, in the last 3-4 years, servicemen say things have really improved because the current payscales and pensions are almost equal to that of Indian Army.

The former R&AW officer said that though Indian government is “under debt of gratitude” to SFF troops, “the bureaucracy was rule bound”. “These were foreigners; so the question of paying pensions initially did not arise. It was a very clandestine affair. They were directly under the cabinet secretariat, so these were unaccountable funds. They used to get what R&AW sources would get in early days, which was not a great deal of money. It was only after the 4th pay commission that things began improving and that, some Tibetans soldiers born in India began getting pensions.”

Given the circumstances, many Bangladesh war veterans were then forced to work as chowkidaars, porters or garment businessmen to make ends meet.

72-year old Sonam, for example, worked as a carpenter. As one enters his small, non-descript house on Jogiwara road, wood-dust is scattered all around. Inside, the room is cramped with books and files belonging to his three children, idols of Tibetan deities and a picture of him in the uniform proudly displayed on one of the walls.

When he retired in 1982 at the post equivalent to sepoy, he got Rs 11,000. “Almost all of it was spent on my children’s education. Never got a chance to invest or think of future,” Sonam said.

To earn a living, he began working as a carpenter. The wooden prayer table and book shelf at his home are fine examples of his skill. His wife still works in the local handicrafts unit, making Rs 800 a month. “The only good thing is that the house is given to her by handicrafts department and we will get to live here till she is alive. Recently, 22 gave me a smart card to buy rations from Army canteen.” Sonam’s daughter is relieved that they have now also got medical insurance; last year when he got Tuberculosis, they paid for treatment from their own savings.

Similarly, Bhuchung Tsering worked as a second-hand clothes businessman for 28 years, procuring garments from Delhi and selling them in Manali. “In the end, I had become too weak. The municipality would constantly trouble us; make us go away from roads, snatch away our goods. I could no longer cope with it, so I came to this old age home. Here, clothes, food, medical checkup is all free,” he told Scroll.

His friend, Pema Wangden, whose unit was posted in Demagiri during Bangladesh war and was responsible for supplying rations and reinforcements to troops, retired in 1983 after 19 years of service following a severe back injury. He got Rs 8000 in all.

Jampling old age home in-charge, Wangchen, himself an ex-serviceman, said most retired Tutu soldiers have neither savings nor a family to take care of them. As such, 20 seats have been reserved for ex-servicemen in the old age home.

Ex-Servicemen Association records state that 349 members in Dharamshala and around 6000-7000 across India have got no pensions.

Some of them, however, get financial assistance from CTA and SFF based on how “critical” their needs are.

As per June 2013, SFF was paying Rs 1000 per month to 1127 soldiers who retired before 1985 as “financial assistance”.

The Department of Home under Central Tibetan Administration also provides Rs 1300 monthly to 202 ex-servicemen who retired before 1985 and Rs 1000 monthly to 200 ex-servicemen who retired between 1985 and 2008 across 41 settlements in North East, Himachal Pradesh, South India and Nepal, Additional Secretary Tsewang Dolma told Scroll.

Most ex-servicemen, however, laugh away at the amounts. “The average monthly expenditure of an elderly is minimum Rs 1000-2000 and goes up to Rs 7000 in case of severe health issues. What will Rs 1000 do in today’s day and age?”

A case has been going on reportedly in the headquarters in Chakrata for many years, where it is being “considered to pay some financial assistance to the SFF veterans”. Refusing to be identified, a young Tibetan from Darjeeling now based in Delhi, whose father fought during 1971, says he “waited for dues all his life” before he eventually died of lung cancer last year.

All said and done, what pinches these ex-servicemen most is not even the non-payment of dues but the fact that they were never allowed to fight against the Chinese – which was the real aim behind raising this force.

A 79-year old monk I met at Namgyal monastery recounted the initial reaction to the orders. “300 monks from my monastery had joined SFF. The feeling did crop up that Pakistan was not our personal enemy. But India was in trouble and we had to obey orders. We take our role as guests seriously,” he said, smiling. After retiring, the soldier went back to his monastic life. “There were no funds to sustain myself. So, I came back.”

He, however, does not feel dejected at being denied recognition or monetary benefits. “Our establishment was a secret and we understand that. Humne Hindustan ka namak khaya, badle mein unki madad ki. Hisaab barabar.”