When the violence of South Asia’s colonial history appears in academic scholarship, it largely does so only in certain forms: narratives of rebellion and resistance, religious or ethnic violence, and cataclysmic events. Framing violence in this way displaces it onto the colonised and underestimates the endemic, everyday forms of violence through which colonialism operated. Such erasure is not unique to Indian history. It merely illustrates the ways in which violence has been written out of the history of Britain’s imperial past.

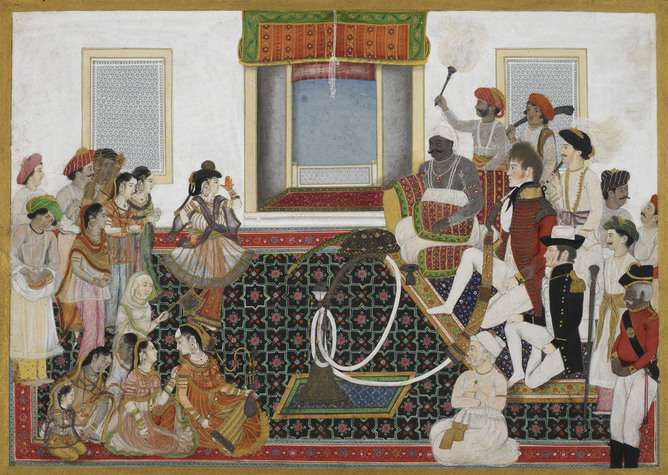

Indian Artist, Delhi, Mahadaji Sindhia entertaining a British naval officer and military officer with a Nautch c. 1815-20.

Source: British Library

Indeed, the past decade has witnessed renewed attempts to “whitewash” Britain’s imperial exploits. In 2012 it was revealed that thousands of documents detailing acts of violence committed on colonised peoples in the final years of British rule had been either systematically destroyed or ferreted away in a secret Foreign Office archive. These revelations were to a large extent ignored or downplayed by the mainstream media.

Looking the other way

Such processes of silencing ensure that belief in a benign and benevolent imperialism remains predominant in Britain. The idea that the purpose was not to appropriate land, labour and goods but to impart the benefits of British civilisation to peoples deemed in need of it is far from rare. As journalist George Monbiot has observed in his struggle to explain the reason for Britain’s amnesia in regard to the violence of its imperial past:

The myths of empire are so well-established that we appear to blot out countervailing stories even as they are told.

The reality of empire, remains, therefore, “untroubled by the evidence”.

Elizabeth Butler (Lady Butler), The Remnants of an Army, 1879.

Source: Tate

Museums and public galleries have played a key role in such a process of silencing. This is in spite of the fact that many of the non-Western collections in them were acquired through colonial conquest, exploitation and looting.

Although some British museums have begun to make colonial histories apparent in their displays, many still erase them by presenting objects with contested histories as examples of “art” or as representative ethnographic “types”. Such public museum spaces also legitimise and aestheticise violence by encouraging visitors to view mutilated deities or headless torsos as artistic masterpieces to be admired and coveted.

Unknown Mende artist, Pair of Female Figures on a Stand before 1911, carved wood.

Source: National Museums Liverpool

Such processes hinder our understandings of the nature of empire and its impact on both colonisers and colonised. This is a particularly pressing concern in light of both the global escalation, since the late 20th century, of new modes of violence, ranging from new neo-imperial wars and regimes of occupation, to the deployment of new technologies of violence, such as drone attacks and private security forces (David Harvey and others have referred to this as the “new imperialism”) and of the rise of ethno-nationalist and religious fundamentalisms.

The perpetuation of such myths also prevents a reckoning with Britain’s imperial past. For a nation state that was forged, in large measure, through empire, and whose identity has been considerably challenged by its demise – most recently by the Scottish referendum on independence and the ongoing debate about Britain’s place in Europe – such a reckoning is, undoubtedly, long overdue.

Sonia Boyce, Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great, 1986.

Source: Sonia Boyce

Artist and empire

Art is, perhaps, one of the best mediums through which to attempt such a reckoning. And so Tate Britain’s latest exhibition, Artist and Empire, could not be more welcome. Not only is culture vital to the construction and maintenance of imperial and colonial regimes, but as Paul Gilroy observes in his preface to the exhibition catalogue, it can:

Help to reconcile the tasks of remembering and working through Britain’s imperial past with the different labour of building its post-colonial future.

It therefore has the ability to alter Britain’s understanding of itself.

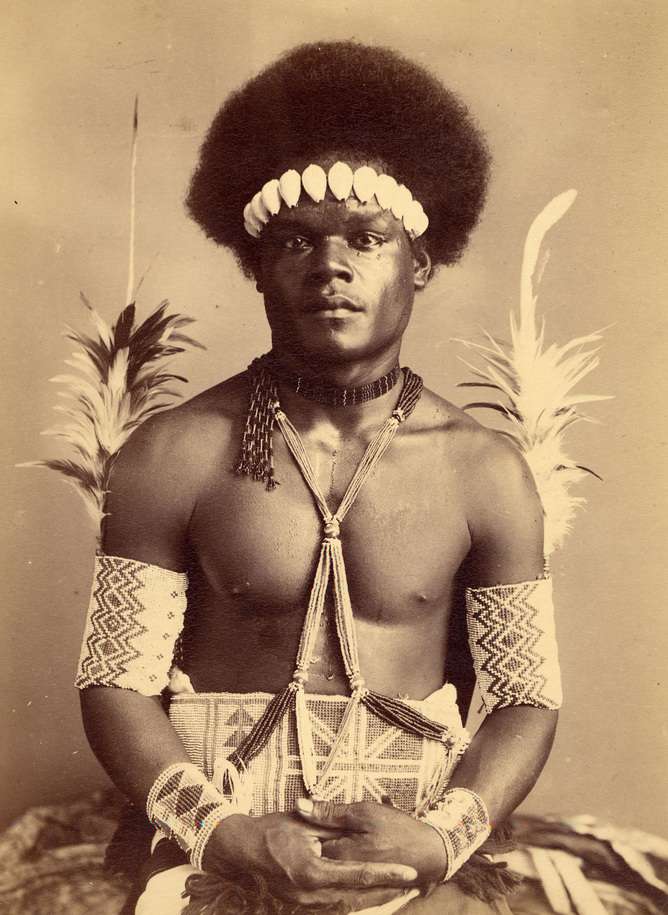

Unknown photographer, a Man from Malaita in Fiji late 19th century.

Source: The British Museum

The Tate exhibition is well aware of the challenges of remembering and representing empire. It reveals the way that art operated as a form of cultural imperialism by incorporating a wide range of images and objects produced by both British artists and artists from former colonial contexts – from iconic imperial paintings to maps, photographs, and artefacts. But the show also avoids over-simplifying what exhibition curator Alison Smith terms “the tangled histories embodied by objects”.

It also makes the bold move of expanding the time span of the exhibition to the present. This avoids not only imposing an artificial boundary as to when the Empire ended (if, in fact, we can say that it actually did) but encourages reflection on the legacies of empire in contemporary culture, politics and public debate in both Britain and its former colonies.

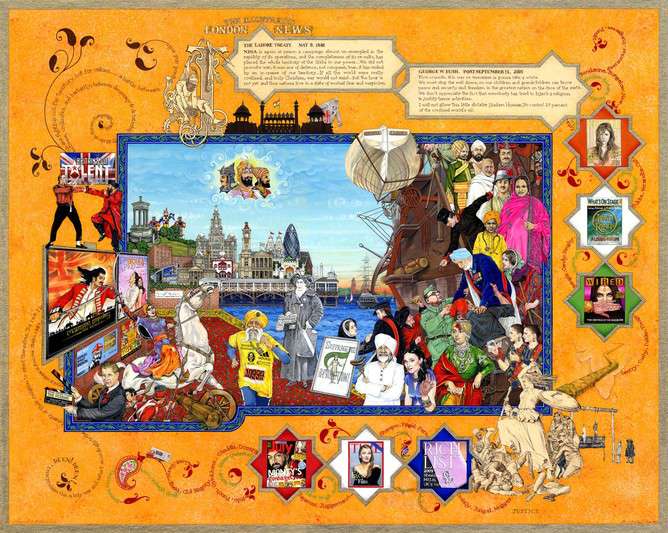

The Singh Twins (b. 1966), EnTWINed, 2009.

Source: Museum of London

But when it comes to violence, the exhibition falls down. While it reveals the provenance of stolen or looted objects and images, it contains few visual representations of violence. Such images do exist, but they aren’t featured here.

What about, for example, the haunting paintings of renowned Bengali (later Bangladeshi) painter Zainul Abedin of the estimated 1.5 to 4 million victims of the 1943 Bengal famine? Or the ostensibly “anthropological” photographs that document the myriad ways, physically, mentally, and emotionally, in which colonised bodies were violated? The exhibition does contain some images of caste in colonial India, but could have gone further.

Such engagement is important, because for Britain to truly reckon with its imperial past, we need to understand much more about the violent nature of that past.

Deana Heath, Senior Lecturer in Indian and Colonial History, University of Liverpool

This article was originally published on The Conversation.