At first glance, such mapping may not seem very useful. After all, harassment is ubiquitous in Indian cities, so how could merely plotting unsafe areas make those spaces safer for women? But for the people who run and use these sites, this is just the overt purpose of the maps. By taking away the pressure of filing formal complaints, they hope that this anonymous, map-based informal reporting system will encourage women to speak out more.

“In India, we have a very low rate of reporting crimes against women, and non-reporting is a classic way of saying there is no problem,” said Hindol Sengupta, founder of WhyPoll, which created a map of 100 unsafe areas in Delhi in 2011. “We need to enforce a culture of reporting.”

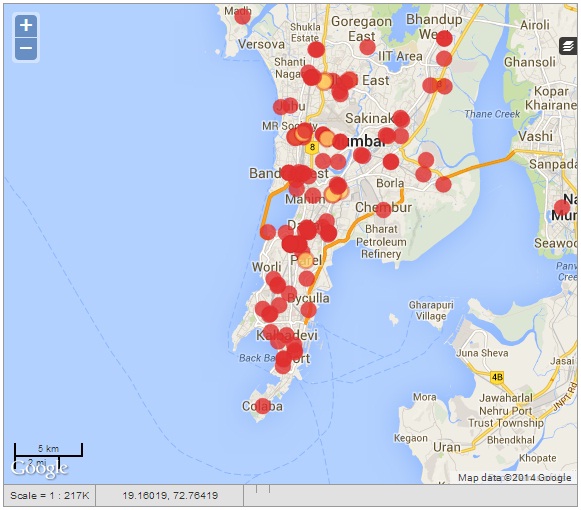

Among the first mapping initiatives to emerge was SafeCity, launched ten days after the Delhi gang rape by four young professionals in Mumbai and Delhi. SafeCity now also partners with WhyPoll. There is also HarassMap Mumbai, launched by non-profit organisation Akshara in November 2013, inspired by an Egyptian mapping site of the same name.

Most of these sites allow users to classify different kinds of harassment, ranging from catcalling, whistling and ogling to groping and rape. The incidents can be reported either by filling out a form on the websites, sending a text message to the organisations or using a mobile app.

“A lot of women are silent about the abuse they face because people tend to blame them for it,” said Surya Velamuri, one of the co-founders of SafeCity. “We created an anonymous forum for women to talk about abuse, and now we also have people recounting stories from back in the 1990s.”

In the past year, the number of reports to SafeCity – both directly and through WhyPoll – has been growing steadily, appearing on the map of India as tiny red dots. So far, it has received more than 2,600 reports from over 50 cities and towns in India. Most of the reports come from Delhi, where SafeCity has an active team of volunteers to spread the word about the map on the ground.

The success of such mapping efforts depends entirely on getting larger numbers of people with access to the internet or to smart phones to keep sending in reports. “If people can see, on a map, how big the issue is, they will put more pressure on the authorities to act,” said Sengupta.

Experts believe mapping is successful largely when the maps are directed at specific audiences. “Maps are a great way of visualising information and can be powerful when they are used by an organisation or institute that has the power to make a difference,” said Nithya Raman, an urban planner and director of Transparent Chennai, an non-profit organisation that promotes research on civic issues by creating maps to highlight them. “The most useful maps are ones that directly involve a group of citizens or figures of authority who can use the information.”

This has been the case with Akshara’s HarassMap Mumbai, which attempts to go beyond identifying unsafe areas by working closely with the local police. “We give the police constant feedback about areas that show up as unsafe on the map, and give them suggestions on how they can intervene,” said Akshara co-founder Nandita Shah.

For the past three years, the NGO has already been conducting safety audits across Mumbai, identifying factors such as poor lighting, densely parked cars or the lack of a police presence to help the authorities improve conditions for women’s safety. “Now with HarassMap, too, we have seen cases of police intervention,” said Shah.

Sometimes, however, just the act of mapping an unsafe locality can lead to change. In 2011, when WhyPoll ranked Delhi’s notorious Nelson Mandela Marg as number one on its list of 100 unsafe areas in the capital, the authorities did react. “Just two weeks later, police patrolling in the area was increased, and today, that road is very secure,” said Sengupta.