I stood in front of the library, little knowing it would turn my world upside down. The house-like structure stood, quiet and forlorn, with its mud-pantiled architecture, wooden blinds on windows and padlocked door, appearing corpselike even in broad daylight like some sort of old bygone government health centre, and giving no indication from any angle that it could also be a library. The entire place had an air of derelict sadness. Perhaps that’s why, standing there in front of it, I remembered Pau’s face, a face marked by anguish and annoyance.

Perhaps, Pau honestly thought I took pleasure in annoying him. But that was not always the case. On the contrary, I could tell he got upset seeing me happy.

There was his annoyance at hearing music coming from my room. He would immediately drop in, pull out the wire, wrap it around the tape recorder, pick up the recorder, and trot out. All the while, his dagger-sharp eyes would glare “no more happiness for you, son”, which shivered my spine into pieces.

Then there was his continuing displeasure at seeing me sleep into the mornings. He would rudely shake me – I am convinced that it was to interrupt the smile playing on my face – and yell in my ear, “It’s ten o’clock. Get up and study.”

“What should I study?” I would ask sleepily, for I had finished my college exams, the results were also out, and I had passed with good marks. “Read your course books again. You never know from where they’ll ask questions in the job interview. I remember they had asked me a chemistry question out of the blue. If only I’d answered, I would have been someone else and somewhere else today!”

“That was a different era, Pau, this is different. This is 2007. The 21st century!” I would try to reason out. But every time, like a stubborn child, he yelled, “No. No. No. Times haven’t changed. Read.” And I retorted, “Don’t tell me again and again, Pau. That’s why I hate reading.”

Such conversations ended the way all our conversations ended these days:

1. Disappointed in me, my Pau would leave the room with bowed head, and withdraw to his room.

2. Disappointed in Pau, I would leave the house in annoyance, and walk out.

With an ocean of regretful anger erupting inside me, I alternately berated myself for having hurt Pau, or cursed Pau for hurting me. While walking, I narrated to my Imbelo the illogical antics and unreasonable demands of my father, to which she once said, “Why do you keep condemning your father?” It then occurred to me that perhaps I tend to scorn everything he does, or perhaps even my ordinary remarks are construed as criticism. With books, I had established a shifting, complex relationship – a relationship filled with less love, and more annoyance.

And I held my father responsible for it.

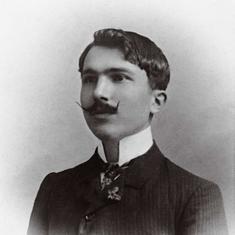

I remember, in my childhood years, Pau delighted in bringing me children’s books every month. I loved the books, a pleasure I indulged in, to the extent that I slept with them beside me in bed. One day, on the way back after buying me a book, Pau and I went to his friend’s place. We used to call him Wrestler Uncle. He was a heavily built man with a thick moustache and thicker arms. His son, Ramu, was eight years older than me but treated me his age. He was my hero, my big brother. The door was open. Ramu was screaming while Uncle smacked him on the face, holding him by the throat.

My Pau hastily went to separate them, but Uncle was in a rage. He pushed Pau away and, with agile hands, lifted his son and threw him on the bed the way he would slam an opponent wrestler down in the arena ring. Then he trumpeted like an elephant, “Beware, if you get up from bed!” Ramu lay there crying, agonising, groaning. I was numbed with terror by the whole grotesque scene, not knowing what crime Ramu had committed.

Uncle finally, at Pau’s insistence, opened his mouth, “This little rascal, he was reading a novel. You hear me? Such a young fellow and reading a novel!”

“It’s not a crime, my friend, that you should beat him so mercilessly,” Pau said softly, in Ramu’s defence. But ignoring my father’s soothing tone, Uncle continued angrily, “I will break his leg if he reads a novel again. He won’t read his course books, no sir, as if his grandmother would die if he touched them. But he’ll happily read a novel the whole day, that too, hiding under the bed. I’ll kill the bastard, make mincemeat out of him.”

Excerpted with permission from Simsim, Geet Chaturvedi, translated from the Hindi by Anita Gopalan, Penguin India.