From 18 September 2024, spread across three phases, Jammu and Kashmir voted in its first assembly elections in a decade. Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar waxed lyrical on the subject, quite literally: “Lambi kataron mein chhupi hai badalte surat-e-haal yani jamhooriyat ki kahani. Roshan ummeedein ab khud karengi gawah apni taqdeer-e-bayani. Jamhooriyat ke jashn mein aapki shirkat duniya dekhegi napak iraadon ke shikasht ki kahani,” he intoned. (These long lines tell the story of changing times and rekindled hopes; your participation in the festival of democracy signals the defeat of those with nefarious intentions.)

Although three Lok Sabha elections, in 2014, 2019 and 2024, were held in Jammu and Kashmir, June 2014 was the last time that Vidhan Sabha elections were held. Apart from the timing, the 2024 elections were significant because they would follow the delimitation process. This involved redrawing the boundaries of parliamentary and assembly constituencies based on population data from the most recent census (2011) to ensure equal representation. Completed in May 2022, this process would increase the total number of seats in the assembly to 114, with 24 seats reserved for Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. The remaining 90 seats would be contested, with 43 in the southern Jammu region and 47 in Kashmir to the north.

Omar welcomed the announcement, saying his party was ready for the elections. “Der aaye durust aaye. [Better late than never.] The National Conference was ready for this day.” There was a lot of talk, after the announcement of the poll dates, about democracy winning the day. Union Home Minister Amit Shah said, “The assembly election will further strengthen the roots of democracy, opening the door to a new period of development for the region.”

Watching this, I didn’t know about democracy – but what I did agree with was the fact that these elections were going to be even bigger than those of 1996. Taking place as they were a mere handful of months after the Lok Sabha elections, the NC – and the Abdullahs – had a lot to prove.

The results of the general elections had seen the rise and success of what are known as BJP’s B-teams (or C-teams, depending on who we’re talking about!) in the Valley. Omar had lost in Baramulla to Engineer Rashid, an independent candidate backed by the Awami Ittehad Party (and jailed since 2019, in a terror-funding case).

The assembly elections, then, pointed to the need for the Abdullahs to unite with the Congress, to pull together against adverse circumstances. More importantly, Farooq needed to step up to the plate, with his customary aplomb. Since 2020, and particularly in the aftermath of the Lok Sabha elections, Doctor Sahib had been quieter, more sust, as we Punjabis call it. He wasn’t his usual ebullient, dynamic self, and he kept to himself in a way he never had before, at least not since I had known him.

As someone who has seen Farooq rise above every kitchen sink that life has flung at him, I must confess that this time, I was worried. I had no doubts about Farooq’s abilities as a politician, but this time, it would take a harder pull. In the run-up to the assembly elections, Doctor Sahib proved yet again that he was far from being beaten. In an interview given to veteran journalist Neerja Chowdhury of The Indian Express, Farooq insisted that it was going to be difficult to fool the people of Kashmir a second time around. “We have tried to tell them the truth …” he said. “They [the people] know they [a reference to Engineer Rashid] were released to divide our votes. But they won’t be able to divide our votes. Ya hum bewakoof hain, ya woh bewakoof hain [Either we are fools, or they are] … A man charged with receiving Pakistani money, also calling for a plebiscite and a free J&K, how has he suddenly become a friend of the BJP?” It was a rhetorical question, of course – but it was a defiant one. Farooq was not going to give up without a fight, but more importantly, as far as I was concerned, he had hope.

To my mind, he has never lost that hope. It is what has kept him going for so many turbulent decades of Kashmiri politics. Doctor Sahib’s forming of the PAGD with the other political parties of Jammu and Kashmir in 2020 was a masterstroke in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370. The first PAGD meeting, at Mehbooba Mufti’s home, was attended by Mehbooba herself, Mehboob Beg, Farooq, the Awami NC’s Muzaffar Shah, Jammu and Kashmir People’s Movement’s Javaid Mustafa and CPI-M leader MY Tarigami. The statements that came from the PAGD members underlined Farooq’s credo of unity and his understanding of the historical baggage that the Valley carried. “We have faced everything together and want to assure the people of Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh that we will always raise their voices, whether in Parliament or elsewhere. Do not misunderstand us. We shall be on the side of people, who are suffering,” said Tarigami. Farooq himself quoted his father and said, “Like him, I will stay in fire and douse the flames. We will fight in Parliament and raise issues … Our doors are never shut. If and when called [by the Centre], we will go.”

This call for understanding has been constant since the abrogation of Article 370. I have written in numerous articles that, despite the hue and cry around its abrogation, Article 370 was a mere fig leaf over Kashmiri dignity. It had been abolished in all but name since 1975, when Sheikh Abdullah and Indira Gandhi signed an accord, under which the Sheikh agreed to accept the position of chief minister under the Indian Constitution, effectively dropping the demand for a plebiscite. Article 370 gave legal and constitutional validity to the accession and sought to define the state’s special status within the Indian Union. This essentially was the political safeguard that the Kashmiri Muslim sought for the protection of Kashmiriyat and his identity. For all other purposes, Kashmir had become a part of India.

Problems arose subsequently when Kashmiris began to perceive that India was reneging on preserving their special status and defending their unique identity. At a fundamental level, Kashmiri movements since then have not focused as much on leaving India as on defending their spiritual and political identity: Kashmiriyat. Delhi’s constant stonewalling and backtracking has led to a change in Kashmiriyat on the ground – and of that I think there can be no doubt, irrespective of whom you speak to in Kashmir. I have still held on to hope. If you had asked me, in 2016, like Nandita Haksar did at the Tata Literature Live Festival, whether Kashmiriyat was over, I would have argued with you – as I did with her. I kept asking her, “How can Kashmiriyat be over?”

But the truth of it is that 2016 was the beginning of the end of Kashmir as we knew it. It was the year Burhan Wani was killed by security forces. Wani’s death sparked massive protests across the Valley, in what became the worst span of unrest in the region since 2010. Huge crowds turned out to attend Wani’s funeral as his body, wrapped in the flag of Pakistan, was buried next to his brother Khalid, in Tral. Militants present at the funeral offered Wani a three-volley salute. The unrest across the state was immense, with separatist leaders calling for a statewide shutdown and police and security forces repeatedly attacked by mobs. Stone pelting was reported across the Valley, with Kashmiri Pandits fleeing again. The internet was shut down and the national highway was closed off. Thousands – civilians and military personnel alike – were injured and nearly a hundred people lost their lives. DS Hooda of the Northern Command appealed for peace. “What can the army possibly do?” he said in a statement on 16 June 2016. “We are helpless when entire villages come out in support of militancy and against us.”

Force, when applied, will always lead to increased separatism and radicalism. That is a fact of life and it has been proven in insurgencies across India, time and again, from the Naxals to the situation in the Northeast. Why, then, go to the abrasive length of abrogating Article 370 legally? Farooq has often plaintively asked me this question too. More than anything, his awareness of just how badly this can damage the state has been painful for him. Indeed, the abrogation was a sad day for Jammu and Kashmir. One gets the feeling that it was totally uncalled for. It was a bad move, because Article 370 was a hollow provision. There was no need to have touched it, for it prevented nothing. Small wonder, then, that Kashmiriyat as it once used to be in the old days stands in danger of extinction today. Over the years, it has been clad in all kinds of hues of nationalism, brushing aside any question of its evolution and original historical context. To my mind, however, Kashmiriyat is beyond a concrete definition. The best way that I can think of describing it is “togetherness”, or “unity”. Farooq is the last of the Kashmiri leaders to espouse this trait. He not only emphasises it but he also embodies it. As long as he is alive, so too is Kashmiriyat.

But there is no denying that he is a worried man – and has been since 2019. Abrogation is one thing. Bifurcation of the state is worse, because now you’re going back from what you were trying to do in 2014. At least, that was the impression when the BJP and the PDP came together. Then, there was just that glimmer of hope that maybe now Jammu and Srinagar would come closer together. Mufti Sahib overestimated himself and underestimated Narendra Modi. Indeed, bifurcation, in my opinion, would have a much worse impact. In 2008, the polarisation between Jammu and Kashmir began with the Amarnath land agitation. With the bifurcation, the seeds were sown for communalism to flourish further. Don’t forget that Jammu is not just Hindu, it has a substantial Muslim and Sikh population as well. To dismiss it as just a Hindu-majority region would be wrong. This is precisely where the NC – and Farooq – will come in. Time and again, articles and opinion pieces claiming that the NC is over have been written. But if there is a party that has real historical roots in Kashmir, and that unites it, it is the NC. If there is a family with whom Kashmir has an instant association, it is the Abdullahs.

But you see, that has always been a problem in the state: the disability in recognising the importance of Farooq. As I have come to know him, I have observed that he understands Pakistan, he understands Kashmir, he understands India and he understands human beings. The abrogation of 370, in Farooq’s eyes, marked a shift in the way politics is being conducted in India. It also highlighted for him the abysmal state of regional leadership in the state. Leadership in the state has been a perennial failure: the separatists were useless; the so-called mainstream has also not been the best. The Centre took advantage of this as well as of the weakness of the Congress party and the so-called Opposition in 2019.

In 2019, I gave an interview to The Print, to Jyoti Malhotra, in which I asked the question: What has stopped Rahul and Priyanka from going to Kashmir when they have a loose kind of alliance with the NC? After all, if that alliance had been a serious one, even then, the Congress would have found a strong foothold in the state. In 2019, I went so far as to say that the Congress had abandoned Jammu and Kashmir. Three years later, when Rahul Gandhi began walking across the length and breadth of India in 2022, Farooq was not just fascinated, but genuinely inspired. Here again, I found something to admire in the great man. Time and again, he had been let down by the Congress. Over the years, from Indira to Rahul, the Congress had taken him as lightly as anyone else. But Farooq never lost hope for some kind of alliance, for some kind of bridge to be built between Delhi and Srinagar. In his eyes, the hope for a better India, and a better Delhi that recognises and gives Kashmir its true worth, is what keeps him going.

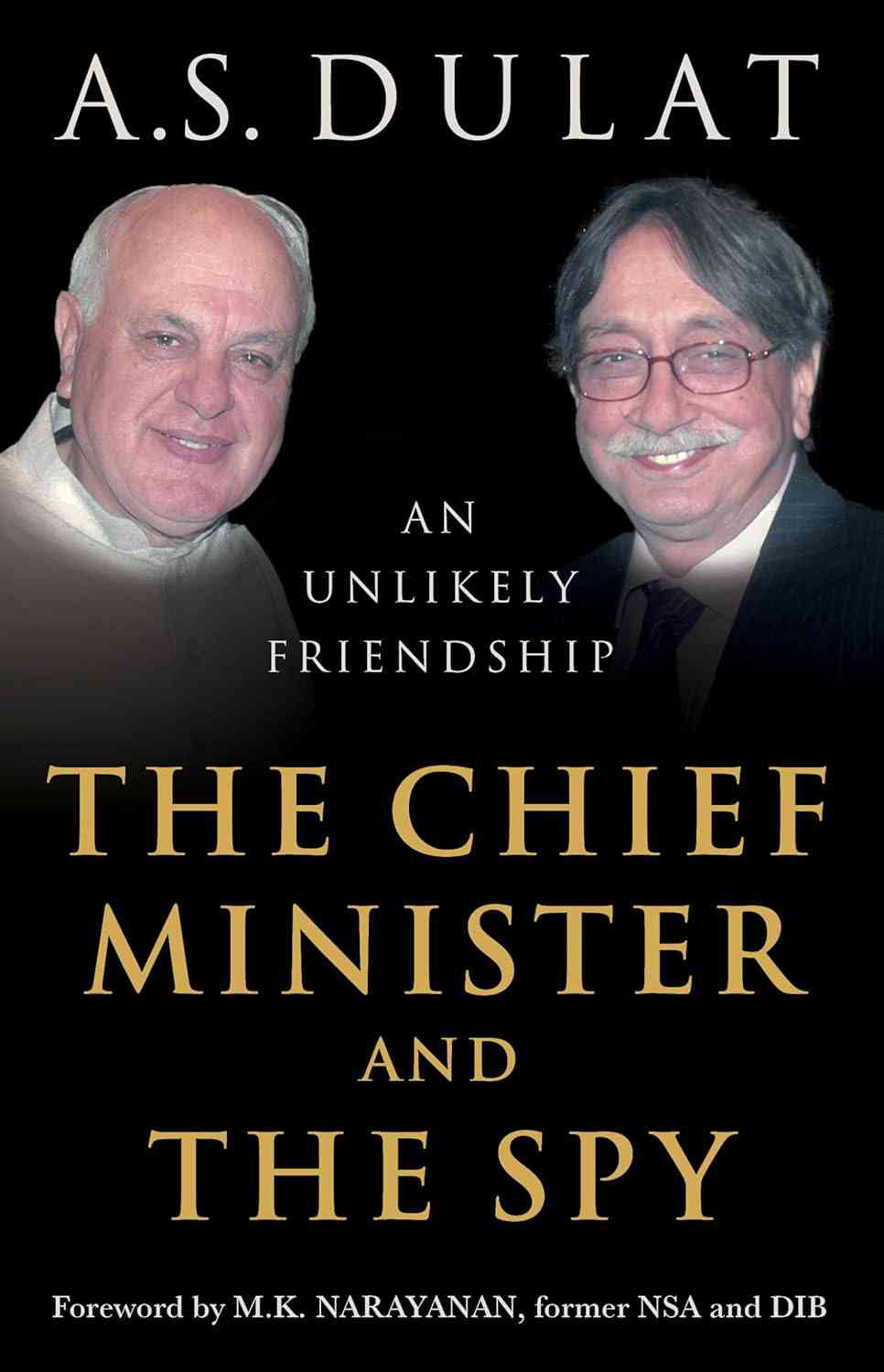

Excerpted with permission from The Chief Minister and the Spy: An Unlikely Friendship, AS Dulat, Juggernaut.