In September 2023, Naga in north Sikkim resembled something of a model village. The panchayat and the residents had worked towards the aim of developing it as the sub-division headquarters of Mangan district, building good roads, and setting up impressive school and healthcare facilities.

But on October 4, 2023, the dream came crashing down.

That night, Nimo Lepcha, a resident of the village, felt his home shake. He rushed out, thinking it was an earthquake. But soon, news spread that the Teesta, a swift river that flowed through the valley below Naga, had flooded, sweeping away low-lying houses and crucial bridges that connected villages across the waters. While the waters did not reach Naga, the flood cut away the mountain under it, triggering a landslide that destabilised several houses and left their walls cracked.

Over the next two days, Nimo’s home continued to shake and develop cracks. Finally, he decided to move his family and important belongings to another house they owned in a part of the village that seemed less affected by the landslide.

Over the following months, life in the village returned to normal and people resumed their routines. But the calm was short-lived.

Ten months later, in early July 2024, when monsoons arrived in the region and heavy rain pounded the already weakened slope, it collapsed, taking more than 70 houses in Naga with it, and leaving another 140 or so at grave risk. No lives were lost because residents had shifted to other homes, fearing that the buildings were unsafe. The village’s main road also sank in the landslides and became unmotorable. Naga no longer has the infrastructure to host a sub-division.

“There is no future here,” said Nimo, who, like several activists and locals who spoke to Scroll, requested anonymity because they feared repercussions from authorities.

The same October night that Nimo rushed out of his home, another dream died two hours later, 90 km downstream in Melli, a town in West Bengal right next to the Teesta. After the local police began alerting people about the incoming flood, Leboon Thapa and his family rushed out of their home with only their important documents. The day after the flood, 23-year-old Leboon waded through the silt in his damaged home with the hope of retrieving his most prized possessions – medals he had won while playing state-level football.

Much to his relief, he found the medals that morning. But the flood has left his lifelong ambition of playing the sport professionally hanging by a thread – though he has been selected to play for a football club in Assam, he is conflicted about taking up the opportunity because he believes his family needs his financial support.

Currently, Leboon and his parents share a large barrack-style room in a temporary relief centre in Melli with two other families. Inside, a table with a stove serves as a kitchen, and beds are set with mosquito nets. Two common toilets are used by the 12 families that live here in five such shelters.

“Should I be here to support my family or go out to play? This decision is putting a lot of mental pressure on me,” said Leboon. “I worry that I’ll go and play, and come back to find that the situation of my family is still the same.”

The flood that upended lives from Naga to Melli that year was a glacial lake outburst flood, or GLOF. Such floods occur when a lake formed by a melting glacier suddenly collapses or overflows due to an external trigger, causing a large volume of water to cascade downstream. In October 2023, the main trigger was the collapse of a portion of a moraine, a natural embankment that holds water in, of the South Lhonak lake in north-western Sikkim.

The flood impacted 100 villages in Sikkim, killing 55 people and leaving over 70 missing. Over 7,000 people were displaced.

According to an assessment of the state disaster management authority, around 6,000 people were shifted to relief camps, most near the town of Singtam. Neither the West Bengal disaster management authority, nor the national one reported numbers from the state as of a week after the disaster – but according to a resident of Kalimpong district who had access to official data, as of October 12 that year, two people were confirmed dead in the district, and 12 were missing, while property worth around Rs 62 crore had been destroyed.

In Rangpo, also in Kalimpong district, Scroll met a resident who lost three family members and another who saw a family of three washed away in their car.

South Lhonak lake is not the only threat to downstream areas. Sikkim is home to 232 glacial lakes, of which 31 have been identified as being at between “medium” and “very high” risk of floods.

In fact, the entire Himalayan region has seen massive expansions in the sizes of many of its glacial lakes – almost 89% of nearly 700 lakes that expanded between 1984 to 2023 doubled in size, the Indian Space Research Organisation has found.

Studies hold climate change responsible for this – as temperatures rise, glaciers are melting and retreating faster, leaving behind lakes made up of melted water and increasing the size of existing lakes. “The frequency and intensity of GLOFs is definitely because of climate change,” said Sandip Tanu Mandal, a glacial geomorphologist associated with the Centre for the Study of Regional Development at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “Melting is faster in the eastern Himalayas, than it is in the western and northern.”

Those living downstream from the lakes are only too aware of their dangers. “These lakes are only increasing and I am certain that we will see more such GLOFs in my lifetime,” said a former activist and resident of Mangan, about 90 km downstream of the South Lhonak lake. What adds to their worries is that the government continues to build large infrastructure projects such as hydropower dams in the regions, though these have been found to exacerbate the extent of flood damage.

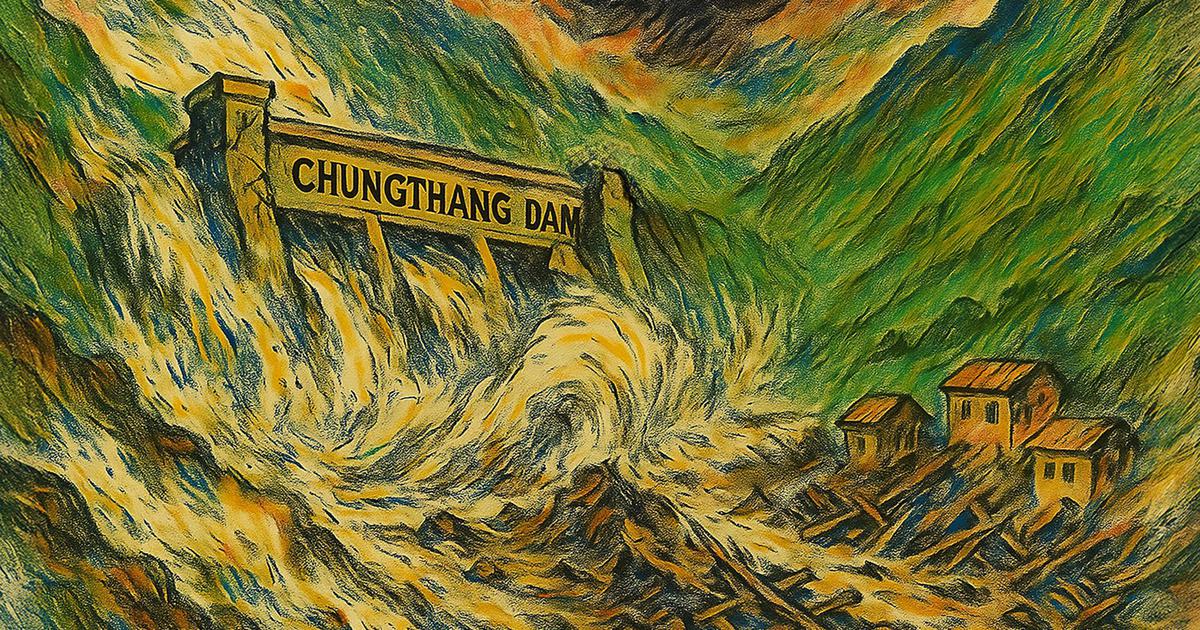

In October 2023, the flood that originated from the South Lhonak glacial lake acquired more ferocity after it ripped apart one of India’s largest hydropower projects, the 1200-megawatt Teesta Stage III in Chungthang, because its gates could not be opened in time in 2023 to let floodwater through.

The debris from this dam and a string of other such dams on the Teesta swirled with the floodwaters and caused extensive destruction downstream in Sikkim and West Bengal.

In April, a year and a half after the flood, Scroll travelled about 200 km along the Teesta from Bagdogra in West Bengal to Chungthang in Sikkim.

We drove through dusty roads still strewn with debris from the landslides that followed the October 2023 flood, and met impacted families in the low-lying villages of Teesta Bazaar, Melli and Rangpo, before driving up to higher altitudes, to North Sikkim’s Naga, Mangan and Dzongu villages. We ended our journey in Chungthang, a small town that was first to be hit by the flood.

In every place, we found that locals were struggling to resume their normal lives even a year and a half after the disaster. In some cases, as in Naga, this was because the hydrogeological effects continue to play out and cause damage to the region. In others, it was because government rehabilitation measures were either insufficient or flawed.

Even as these problems continue to loom over this vulnerable geography, the government and project proponents are proceeding with work on hydropower dams.

This January, the environment ministry granted environmental clearance to a proposal to rebuild the dam at Chungthang, albeit with some measures intended to guard against flooding – for instance, the dam will have the capacity to allow more than double the volume of water to flow through its gates, will be designed with a more resilient structure, and will be equipped with an early warning system.

Locals are unconvinced these measures will suffice. “They should not be repeating this mistake,” said Mayalmit Lepcha, a resident of Dzongu and general secretary of the Affected Citizens of Teesta, a movement that has resisted dams along the Teesta for almost two decades.

Chungthang should serve as a caution, Mayalmit explained, given that “The dam which took 12 years to build got washed away within ten minutes.”

In responses to emailed queries from Scroll, the state disaster management authority stated that it had taken a “two-pronged approach” to “enhance preparedness and resilience against potential GLOF events”.

The first of these was a “widespread awareness campaign” in places such as community centres and schools “to educate residents about the risks associated with GLOF, the importance of timely evacuation and the role of early warning systems”.

The second comprised “participatory rural appraisals”, a process to “actively involve residents in the process of identifying hazards, mapping resources and developing connect specific evacuation plans”.

The authority also noted that it had developed detailed evacuation maps for communities, which “delineated safe evacuation routes, designated assembly points, and temporary shelters, taking into account the unique topography, accessibility and available resources of each region”. It added that it had also carried out “various expeditions and scientific studies” of high-risk glacial lakes, and that based on the findings, “mitigation strategies will be developed to address potential glacial lake outburst flood risks”.

As of publication, the West Bengal government and the environment ministry had not responded to emailed queries – this story will be updated if they do.

The government knew about the risk that glacial lakes presented as far back as 2007.

While granting environmental clearance in 1999 to a large hydropower project on the river, Teesta Stage V, the environment ministry asked the project proponent to conduct a study of the carrying capacity of the river. Published in 2007, the study clearly noted that South Lhonak had a history of glacial lake outburst floods.

From 2012, the Sikkim government and the National Disaster Management Authority took steps to try and tackle the problem, such as draining water out of the lake to reduce its size. Just 15 days before the 2023 flood, they also carried out expeditions to the lakes to install a weather monitoring system and camera. But the lake continued to grow and the flood washed the monitoring systems away.

Later studies had found that, driven by long-term climatic warming, the South Lhonak glacier had rapidly melted and led to an increase in the size of the lake in recent decades – specifically, in the last 45 years, the lake expanded to become more than ten times longer than before and more than five times wider.

But though the government was aware of the risk of the lake flooding, it allowed a string of hydropower projects to be built on the river. Three such projects are currently operational on the river in West Bengal, while in Sikkim, 20 small and large projects have been constructed. Twenty-nine more are under construction in Sikkim’s share of the Teesta. We drove by four of these projects while travelling across the two states – as we moved upstream, more damages to the structures from the 2023 glacial flood were visible.

Mayalmit, the general secretary of the Affected Citizens of Teesta, explained that all these dams exacerbated the impact of the flood in their areas.

“Glacial floods have been happening since many years,” she said. “Earlier, the waters would just flow over. But now the impact of the floods have increased due to the water that was accumulated in the dam.”

Specifically, she noted, since the dams already had accumulated water in their reservoirs, when the cascading waters of the glacial lake were added to them, dam gates would have to be opened to prevent flooding upstream – but this led to massive volumes of water gushing downstream and causing floods there.

Elsewhere, others agreed with this assessment. “If the series of dams were not there, then the only water that would have come would have been from the glacier, the dam’s water would not have come,” said Akbar Lepcha, sitting in the relief shelter in Melli that he shared with his father-in-law.

The problem was not only one of excess water from the dams – locals explained that the structures also blocked the flow of silt and clay, an observation borne out by a 2024 study that looked at data between the 1970s and early 2000s. Yuvan said that when he was a young boy in Teesta Bazaar, which is upstream from the Teesta Low dam III, “no one used to swim in the Teesta because it was so deep”. But, he added, “since the hydropower projects, the sand and silt has become stored on the riverbed and the river has become flat”.

This accumulation of material restricted the river’s flow, which intensified the damage caused by the floods. “The dam acted as a barrier because of which stones, boulders and silt accumulated here, flooding the nearby areas,” Yuvan said.

Local anger against the projects is particularly pronounced because North Sikkim, where many of these dams are located, has seen a strong opposition to the building of large dams for the last two decades under the banner of Affected Citizens of Teesta. On a rainy evening in Dzongu’s Hee Gyalthang village, we met a group of individuals who were among those who spearheaded the movement.

The group was diverse, and included a forest ranger, an agriculturalist, an activist and a Buddhist monk. We were at a Lepcha shaman’s home amidst orange orchards and wild ferns – the young shaman was preparing for the ritual he was about to perform to welcome spring.

Sipping chi, a fermented millet drink, a senior shaman explained why the resistance to hydropower was deeply rooted in their culture. “The Teesta originates from the foothills of the Kanchenjunga mountains,” he said, referring to the peak that the tribe considers to be their birthplace. “Since it flows from where we were created, all our prayers are also to the Teesta. It protects and supports us and the animals.” He added that according to local culture, any change in the flow of the Teesta not only causes floods in the river, but also angers spirits.

With its roots in this local culture, the wider movement, represented by the Affected Citizens of Teesta, challenged in 2007 the building of Teesta Stage III project on environmental grounds in the National Environment Appellate Authority, the body that preceded the National Green Tribunal, and led several protests and hunger strikes in the state and New Delhi. “One of the issues we had raised since the beginning was the damage that could accompany a GLOF situation,” said the former activist.

Though they lost that case, in 2017, the movement also protested to halt the construction of the 520-megawatt Teesta Stage IV hydroproject. This time, they succeeded. “In all, the movement managed to stall the construction of four large projects,” said Mayalmit, standing at the confluence of the rivers Teesta and Rongyong, a sacred point for the Lepchas.

Now, in north Sikkim, the angst against the dams has intensified because of the decision to rebuild the Teesta Stage III dam at Chungthang, which was wrecked in the 2023 flooding. The ministry granted this clearance despite the fact that while evaluating the proposal, the environment appraisal committee in January 2025 raised a concern that “13 potentially dangerous glacial lakes were identified”.

Thus, Mayalmit Lepcha argued, “It’s not activists and locals alone who are pointing out the dangers of these lakes. Even the government said that 13 lakes are at the verge of bursting.”

In fact, the central government has also acknowledged that 47 dams across the country – of which 38 are commissioned and nine are under construction – are likely to be affected by glacial lake outburst floods.

The former activist argued that these projects were fundamentally flawed. “More spillways, increased height of the dam, these are all engineering formulas that are not good enough,” he said.

Even as the government continues to build dams on the Teesta, locals are grappling with the fear of living in places where they still experience the effects of the flood more than a year later.

As we drove from Sikkim’s capital Gangtok towards Naga, around 10 km before the village, we found that large sections of the road were unmetalled and had turned muddy from the intermittent rain that afternoon – driving over them was a task for only the most experienced drivers. In some particularly risky patches, a rivulet flowed down the mountain slope and under a bridge across which vehicles passed – locals call the stream “lanthey khola”, or “troublesome stream” in Nepali, because the patch has seen multiple landslides.

By the time we reached Naga, our driver refused to go beyond the village’s playground because the road had turned to slush – we could see a few bikers ahead, revving their bikes, skidding and falling as they rode over it.

Adjacent to the muddy road was a string of houses that had been reduced to rubble. One such house was Karma Lepcha’s. While the October 2023 flood did not cause any damage to their home, the next year, it collapsed in the landslide. At first, she, her husband and younger daughter moved in with a relative in the same village. But soon after, that house also collapsed as a result of continued landsliding. Then, Karma’s family and the other relatives moved to a school turned into a relief centre for similar victims.

“But even this school has cracks now, when it rains the water comes through the ceiling,” said Karma, who asked to be identified with a pseudonym, as we sat in the school’s courtyard.

Karma has shifted her elder daughter to a school in the larger town of Mangan, where she lives with a relative. “It’s hard for the children to see and bear with this situation,” she said.

While the after-effects have been particularly devastating in Naga, other parts of the region also faced difficulties the following year. In West Bengal’s low-lying areas, the height of the Teesta’s riverbed rose after silt and debris carried by the river during the flood from upstream settled in it, and along its banks.

When the 2024 monsoon came, Teesta overflowed its usual levels again, and carried masses of this silt and sand, and water, into Melli, Teesta Bazaar and Rangpo.

This was evident near Nawang Doma Bhutia’s house in Melli, next to a bridge across the Teesta. The level of the water at the time was low, leaving a pillar of a bridge exposed. It had marks on it to indicate the river level, which showed that the debris that had gathered at its base had itself reached as high as 226 metres – according to the Central Water Commission, if the Teesta flows beyond 227 metres above mean sea level here, the water level is considered dangerous.

“Before 2023, the river flowed much, much below,” said Bhutia, an observation many residents repeated in the towns of Teesta Bazaar and Rangpo. “This area was ours,” Bhutia explained, pointing to what used to be her backyard, where she planted flowers. During the monsoon last year, she said, the river flooded the area. “Now it’s the river’s,” she said with a chuckle.

These days, when it rains, she noted, “I don’t sleep through the night. I keep watching the river and where it is flowing.”

Bhutia’s neighbours’ homes, too, bear the marks of the second bout of flooding – doorways had traces of river sand, and sandbags had been placed across them to prevent water from coming in.

“We see that there is relief that is quickly provided to communities at times of disaster,” said Stephen Lepcha, a community mobiliser with Anugyalaya Darjeeling Diocese Social Service Society, which has been helping communities prepare evacuation maps, and supplied them equipment such as ropes, helmets and life jackets. Stephen added, “What is lacking is a conversation about the future of these communities to more such disasters.”

Families in West Bengal rued the fact that the state provided them with less compensation than the government of Sikkim paid to affected families: in West Bengal, an impacted family received Rs 75,000, while in Sikkim, the amount was Rs 1.5 lakh. “What can 75,000 do?” said Vijayata Dorje, who was staying in a relief centre in Teesta Bazaar. “One cannot even make a toilet with that much money.”

A few kilometres upstream in Melli, 22-year-old Leboon Thapa explained that he spent the compensation money he received on medical care for his family. “We could not have found a new plot of land in that money, anyway,” he said. He looked longingly towards some houses across the Teesta – the portion of Melli that fell on Sikkim’s side. “It’s just a difference of a river, but they got so much more compensation,” he said.

Affected communities are also seeking other solutions that could help alleviate the problems they are facing.

One of these solutions is to clear debris that has accumulated on and along the riverbed, raising water levels. “Because of this debris, the river’s flow is obstructed in the monsoon,” said Bhutia.

The West Bengal government acknowledged the problem and its irrigation department has identified 32 sites further downstream from Melli, from which they plan to remove this sand and silt.

Some argue that the government should continue giving permits and leases to resume sand mining activities in the river, which had been suspended after October 2023. “If the sand mining restarts, it will make us safe since the labour can then clear out the debris and sell it,” Melli’s Ansari.

Residents of Melli are also considering another, unconventional, method to try and protect themselves against floods: asking a company building a train route through the town to dump construction debris on houses along the river bank and cover them completely, to form a kind of raised embankment beyond which residents can relocate.

Leboon’s home is currently completely covered with the debris, and not a sign of its existence remains. His neighbour Roshan Rai’s home is still standing – with marks of silt and damaged walls visible on it. Rai continues to live in this house, and is expecting debris to be dumped over his home in the next two months. “Then till the time the muck settles and we rebuild our home, we will stay in Melli’s relief centre,” Rai said.

In all these towns near the river, like Teesta Bazaar, Melli and Rangpo, locals have also demanded a “protection wall” along the river, which they believe can stop the flow of the river in case of a flash flood. Experts however are unsure of the extent to which such a structure will help. For it to be efficient, “it would require huge amounts of concrete, it will be an engineering challenge”, said Mandal, the glacial geomorphologist. It would also be challenging to build on a slope, as well as prohibitively expensive, he added. “The ideal mitigation would be for the people to move away from the river,” he said.

In Naga, panchayat officials took the initiative to find 13.5 acres of land in the higher slopes of the mountain, to rehabilitate the 140 families whose homes have collapsed or are currently sliding. “Talks with the district administration are currently underway,” an official involved in the discussion said.

But most populations in the area remain vulnerable. Just a week after we left, heavy rains, floods and landslides hit North Sikkim. More than 1,000 tourists were stuck in Chungthang and had to be rescued and taken to Gangtok. In late May and early June too, the state found itself grappling with a similar situation after heavy rains triggered more landslides.

“In the meanwhile, the company has started constructing a new tunnel and is doing some blasting for the dam construction,” said Takchi Lachungpa, a resident of Chungthang. “We can see containers coming in with heavy machinery and construction material. The dam is being rebuilt.”

This report is part of a series supported by the Pulitzer Center.