This is the story of my death.

It occurred when one of my cousins, AK Nongkynrih, known to everybody as Kyrham, passed away.

Kyrham was a fine figure of a man, tall for a Khasi, about five foot ten, and quite handsome. We from the Nongkynrih clan were very proud of him. He was a well-known sociologist. People spoke admiringly of him, critics commended his scholarly books very highly, and the government and sundry organisations frequently sought his expertise.

He went to deliver lectures everywhere, and everywhere he went, he mesmerised his audience. We were so proud that he belonged to the clan – one of the leading personalities of the state, and he was ours, a son of the clan. He was our achiever, our treasure.

When I heard about his sudden passing, I went into deep gloom. He was only in his early 50s – too young to die. “What a loss!” I said to myself. “Imagine the things he could still have contributed to the state and the country! Imagine the books he still could have written!”

I was personally affected because, although we both taught at the North-Eastern Hill University, we hardly met. Why didn’t I fraternise with him more frequently? I remember how he regaled us, whenever we met him, with many of his humorous anecdotes. Why couldn’t I have interacted with him more often and learnt more of his stories?

One of the stories he told us was about Mudong from Jowai who nearly killed a man because he could not stay away from his drinks. The incident happened during the staging of the famous drama of Kiang Nangbah in Jowai.

All Khasis know, I think, the story of Kiang Nangbah, the freedom fighter, and how, in the end, he was captured and publicly hanged to death by the British. Because of that, the organisers placed a noose on stage where Kiang Nangbah, the actor, was supposed to be hanged.

The plan was to let old Mudong pull the noose at a signal from the director, and for that reason, they made him sit alone behind the scenes, where the end of the rope was. They gave him careful instructions and asked him to pull the rope only a little just to take the slack away and make the hanging scene more realistic.

But the trouble was that the hanging scene was the very last one, and the drama was very long, interspersed with songs and dances to allow the organisers to prepare the layout of the scenes to come.

Sitting there alone, behind the scenes, with nothing to do, old Mudong got bored. Fortunately, he had come prepared with a bottle of yiad pynshoh, the local rice spirit. Consequently, as the play progressed from scene to scene, old Mudong progressed from the top to the bottom of the bottle. That top-down progress made him feel quite sleepy, and almost against his will, he leaned against the wall and went to sleep.

Meanwhile, Kiang Nangbah was about to be hanged. The British soldiers put the noose around his neck. Kiang Nangbah made his famous speech about freedom if his head should turn to the east. Then, the commanding officer gave the signal for the hanging. The director, too, gave the signal to old Mudong to pull the rope and stiffen the noose. But old Mudong was fast asleep. When no response came, the director shouted, “Mudong, the rope, the rope!”

Old Mudong suddenly woke up, heard something about the rope, stood up and pulled it as hard as he could, and then held on to it for quite some time, partly because he was still not sure what was going on and partly because he was supporting himself on it, for there was a slight dizziness in his head which threatened to toss him to the floor.

Back on stage, Kiang Nangbah was lifted about three feet from the ground and was dangling at the end of the noose, emitting all sorts of desperate sounds. Luckily, his hands were only loosely tied, and he was able to claw at the rope and relieve the pressure a bit.

The spectators watching the scene thought it was a splendid show. So lifelike! So realistic! They started clapping and shouting. “Shabash, shabash! Bravo, bravo!” they roared.

But the director saw what was happening and shouted at old Mudong to let go. The old man also suddenly realised what he was doing and quickly let go of the rope as if it were burning his hand. Kiang Nangbah fell three feet to the ground with a loud thud. The organisers rushed to get him out of the noose and rubbed his throat to help him breathe.

The moment Kiang Nangbah was able to speak, he cursed Mudong and cried, “Chai won itu i dahbei?” Where’s that motherfucker?

Realising what was happening, the crowd roared with laughter and Kiang Nangbah rushed towards the motherfucker with terrible oaths of vengeance. But Mudong had left from the back door and was running for his life.

I was not the only one shocked and gloomy about Kyrham’s passing. At the time, he had just been voted as the most popular teacher in the university. My colleagues talked of nothing else but his untimely death.

One of my writer friends with whom I used to discuss all things literary was so disturbed by the news of his early death that she said to me, “Please don’t die, okay? What would I do without you?”

Was I that beloved to some of my friends? It warmed my heart, and I wrote a poem, Death on a Birthday, in which I discussed the terrors of living too long and the anguish of dying too early.

Is there a right time for dying? All we can do is be ready for death even as we toil for life.

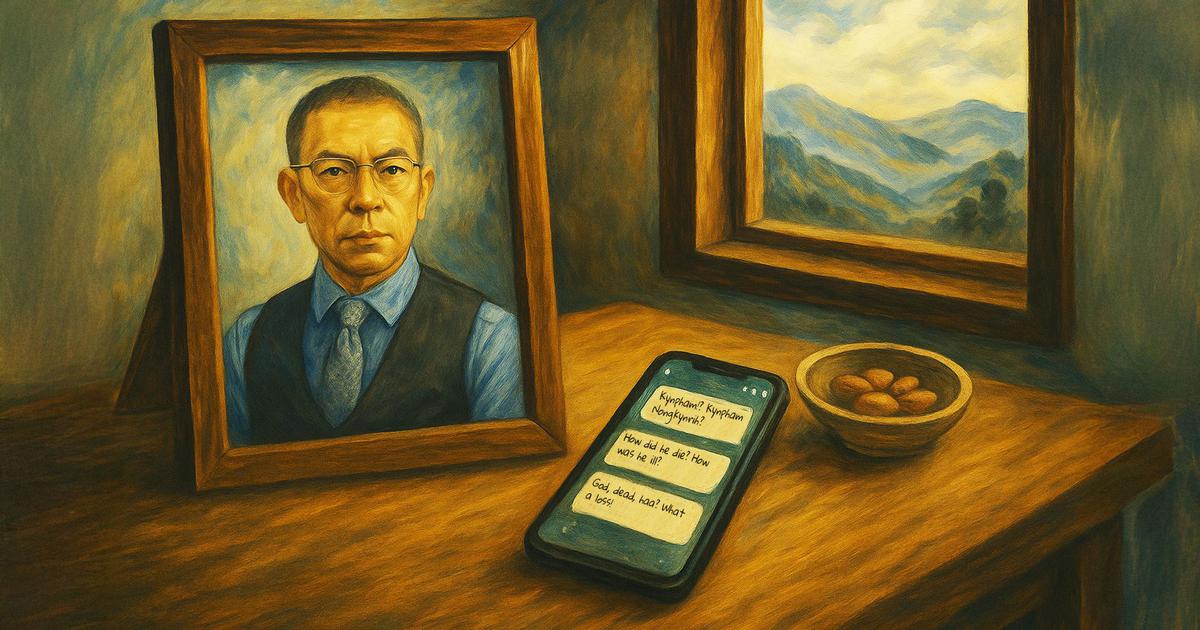

Then my phone started pinging. It was my sister, Thei. She was sharing a WhatsApp message from one of her childhood friends.

The message read: “Dear Thei, I’m shocked to hear about Kynpham’s death! Compared to us, he’s so young. What happened? How was he ill? Was it a long illness? Why didn’t you tell me that he was ill? I would have come to see him. He was such a dear boy. I remember when you and I were school kids…May God grant him eternal rest.”

My phone pinged again. It was one of my nieces on WhatsApp. She was asking, “Maduh, are you all right?’”

“Yes, I’m all right,” I answered. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

After that, she called me. When I said, “Hello,” she said, “Hello, Maduh! My God! It gave me such a fright” and started laughing loudly, nervously.

“What happened?” I asked.

“So many people called me... They asked me if you were dead. One even said, ‘May he eat betel nut in the house of God!’ It was crazy!”

We had a good, long laugh at that.

I was to hear this expression about the betel nut often in the next few hours. When a Khasi refers to a dead person in a conversation, he also says, “Bam kwai ha ïing U Blei” (May he eat betel nut in the house of God).

The invocation points to the Khasi belief that the original home of man is heaven. So, when he dies, if he has earned virtue in life, his soul and his essence go to heaven to be united forever with all the cognate and agnate members of his clan who died before him.

The practice properly belongs to the Khasi religion, which accords a great symbolic significance to the betel nut. Nevertheless, every Khasi, without exception, uses this invocation to wish the dead well and as a charm to avert evil or ill luck whenever they mention the dead.

In the next few minutes, more people enquired about my death. Some were very nice about it.

After that, my phone began to ping without stopping. It was a WhatsApp group created by a local society of authors. I was a member, though I didn’t know many of the people active in the group.

“Ei, I just heard Kynpham is dead!”

“Kynpham!? Kynpham Nongkynrih?”

“God! When?”

“How did he die? How was he ill?”

“My God! Just the other day, I met him! What happened?”

“How old was he?”

“Not very old, I think. Maybe early fifties: 51 or 52.”

“That’s too young to die.”

“Maybe it was a long illness or what?”

“Or maybe a sudden illness?”

“It could be cancer, you know? Sometimes, cancer strikes out of the blue, haa! You are normal; you feel normal, except for minor complaints here and there, and then bam! It hits you, and within days, you are dead.”

“God, dead, haa? What a loss!”

“Yeah, still a lot of contributions from him!”

“Hey! Was he eating too well or what?”

This was a euphemism for hard drinking.

“Yeah, yeah! Maybe that was it, otherwise 52 was too young, you know?”

“Among us, what do we say when a man between 30 and 45 dies?”

“He was stabbed by broken glass?”

“Yeah, yeah! That could have been it.”

“I don’t know. I have never seen him drunk …”

“Maybe he’s one of those ‘standard’ drinkers ... Drinking at night, at home.”

“Death is so unpredictable …”

“Life, you mean?”

“To think Kynpham is gone, just like that!”

I was getting irritated with all these exchanges, so I wrote, “I’m still alive!”

That made many of them laugh. But I didn’t know what else they were saying because I left the group for good. They were not behaving like writers, I thought, just like common gossips.

Next, it was my cousin from Sohra, Just, who called. “Ei, everybody in Sohra is saying you are dead? Are you dead or alive?”’ he asked and laughed aloud.

“Yeah. Many people have texted and called me asking about my death. Tet teri ka! Sngew jem daw pynban!”

I was feeling a bit fed up with all the messages about my death, that was why I said, “Sngew jemdaw pynban.” Among us, jemdaw or jemrngiew means a souring of one’s luck, an enfeeblement of one’s essence or destruction of one’s personality.

My cousin said, “Jemdaw nothing! The old ones used to say if someone dreams about your death, you will live long! Don’t worry; people are just confused between you and Kyrham.”

“I know, but it amazes me how people keep mistaking me for him, you know? I’m just the opposite of him, small and frail …”

“It’s your name! Kynpham: so very much like Kyrham! Many things, too. You and he were born and raised in Sohra: he, from Pdengshnong, and you, from Khliehshnong. Both of you are NEHU professors, and both of you are quite well-known. But the main thing is ignorance. Those ignorant of you take you for Kyrham, and those ignorant of Kyrham take Kyrham for you.”

I knew all that, of course. But it still amazed me that people could have been so confused about us. He was from the Department of Sociology; I’m from the Department of English. He was so outgoing and visible, lecturing everywhere and all that, while I’m almost a recluse, willing to let my books do the talking for me. How could they have made such a mistake?

Then, I started receiving messages from some of my students. It seemed many people were mourning my passing on social media. One obituary especially caught my attention. The girl, Meba, quoted the following words from the website of Northeast Beats:

“...One of the most talented and prolific poets from the Northeast, Nongkynrih’s poetry encompasses a staggering gamut of impulses and thematic concerns, thus lending to his poetry a touch of unparalleled brilliance and splendour.

For the uninitiated, please do go ahead and google his name, and you will see a staggering list of publications … ”

From the Northeast Reads, she quoted this:

“Immerse yourself in the exquisite verses of Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih’s The Yearning of Seeds, a poetic odyssey that transcends borders and resonates with readers across the globe. This captivating collection, rooted in the essence of Meghalaya, envelops you in a tapestry of emotions both familiar and profound.”

Having quoted the texts, she superscribed her obituary on them in bold, white letters, saying, “I will remember you! Humbleness and respect are what I have learnt from you. Thank you (thank you for being with us all those days).”

Meba interspersed her obituary with red hearts, broken hearts and appropriate emojis everywhere.

The student who sent me Meba’s obituary was livid with rage. She thought it was a forbidden thing to grieve the death of a living person. It was sacrilege. She asked me to give her a befitting reply.

But my heart warmed to Meba. Living, I was witnessing my death mourned with such deep feeling. And that, too, by a total stranger. How glad I was that my death would be missed and lamented this way! How unique to witness heartfelt condolences from far and near (the writers excluded, obviously) expressed on your own death! It was a privilege few, if any, would ever have.

Thank you, Kyrham, for the confusion. As you were missed, so was I.

Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih, a poet and novelist, is the writer of the epic-length novel Funeral Nights and The Distaste of the Earth.