See, I’ve known for a while that Louisa May Alcott (yes, the Little Women Alcott) had a secret. Somewhere along the way – maybe in the footnotes of a college textbook or a meandering literary podcast – I’d picked up the fact that Jo March’s creator also wrote pulp fiction. “Blood and thunder” stories, she called them. Sensational tales with opium and bigamy, governesses on the make, and women who were far from angelic (remember sweet Beth at her piano?).

And still, I admit, I never actively sought these stories out. It felt more like literary trivia; like learning that Conan Doyle hated Sherlock Holmes or that RK Narayan self-published Swami and Friends. The sort of thing you register with mild surprise and move on.

Until that sticky, muggy afternoon in Bangkok, when I found myself wandering through Dasa Bookshop – three creaky floors of second-hand books, a spiral staircase, and the kind of musty air-conditioning that feels more like warm breath on your skin. (Go, if you can. It’s worth it.) Tucked between an uninspiring paperback of Jo’s Boys and a lurid-looking Brontë pastiche was a dark, slightly battered hardcover: Behind a Mask: The Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott.

Reader, I gasped. Well, not really, but consider this my own melodramatic hat-tip to Alcott.

Heroines are never quite what they seem

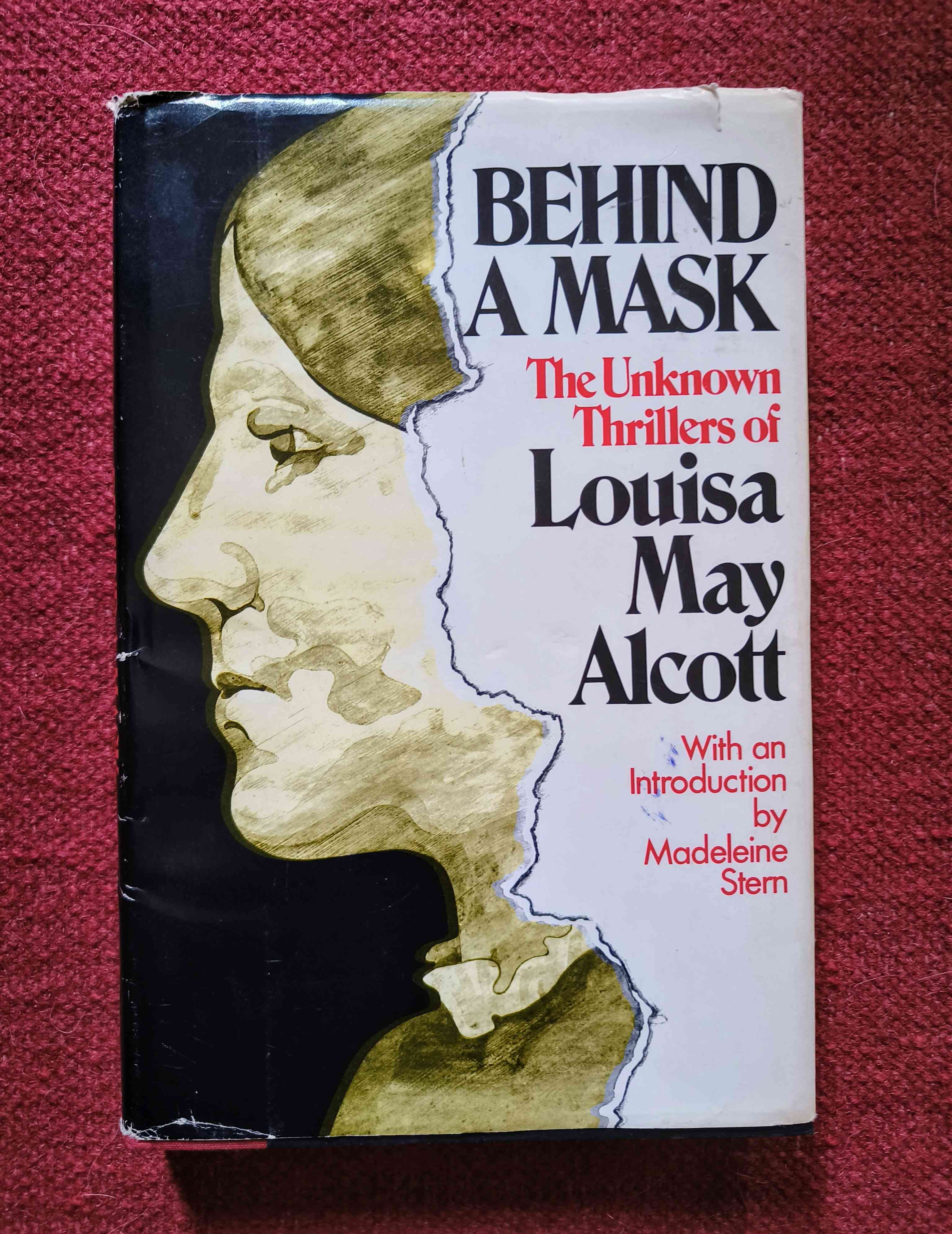

The cover of this book was everything you’d expect from a collection promising revenge, deceit, madness, and “a governess who is not what she seems.” All this from Alcott? It sounded quite unhinged. So, of course, I bought it on the spot. But I didn’t actually read it until months later.

The thing is, I assumed (most erroneously) that it would be interesting in the way old curiosities often are. I’d bought it the way you buy a collector’s item – more for the story about the story, than the story itself.

My fault, entirely, because Behind a Mask isn’t just good. It’s exhilarating and entertaining, and there’s pure joy in its abandon. In that first titular story, consider the governess Jean Muir, delicate and doe-eyed, orchestrating an outrageous social coup, toppling the entire family’s emotional stability like dominoes. It’s a masterclass in deceit, control, and carefully wielded charm. More than anything, it’s just a cracking good story. The others in this collection, edited by Madeleine Stern and first published in 1975 – Pauline’s Passion and Punishment (1863), The Abbot’s Ghost; or, Maurice Treherne’s Temptation (1867), and The Mysterious Key and What It Opened (1867) – all deliver, and not just on their fantastic, delicious names.

Behind a Mask remains my favourite, though, probably because it came first and cracked open that door.

Naturally, I wanted more. And the more I read, the better it got. Alcott wrote these thrillers largely in the 1860s, publishing them anonymously or under the pseudonym AM Barnard in popular weekly papers. The Mysterious Key is the exception, being the only one published under her own name, likely because it was milder than the rest. The others? Full of poison, buried secrets, and heroines who are never quite what they seem.

Here’s another thing about these stories – Alcott was clearly having a grand time writing them. She once confessed that her “natural ambition” was for the lurid style, and called these stories her “lurid fancies.” She once joked about Little Women, likening it to writing “moral pap for the young”. Whether that was true or not, in these pages, Alcott is undeniably having fun.

Of course, the money helped too. At the time, her family was perennially broke, and sensational stories paid well, sometimes double what you could earn for a wholesome tale. Pauline’s Passion and Punishment actually won her $100 as prize money in 1863. But it wasn’t just about income. These stories gave her creative room to stretch as an author, and they are so much more than just literary footnotes or curiosities. From the young girl locked away by a villainous guardian in A Whisper in the Dark, to a stalker pursuing the heroine across Europe in A Long Fatal Love Chase, to duels and gaunting and broken hearts in The Abbot’s Ghost, these are full-bodied, emotionally charged stories, dealing with obsession, revenge, addiction, entrapment. In them, Alcott wrote women who were angry, ambitious, and manipulative. Women who did not suffer nobly but schemed and succeeded. They’re subversive too. Reading Behind a Mask today, you can clearly identify Jean Muir not as a villain but a woman using the few tools the world has left her.

I also enjoyed how reading these stories reframed Little Women for me, adding layers to Jo’s need to write “truth, not romance.” It made the quiet battles in Little Women feel more loaded.

Dutiful and defiant

Of course, today it’s hard not to wonder what Alcott might have written had she felt freer. But maybe it’s that very tension, between the dutiful and the defiant, that gives her work its staying power. That, and the fact that she clearly had a brilliant time letting her imagination run wild.

None of these thrillers are curiosities anymore. They reminded me that writers, like their characters, are rarely just one thing – that their own varied and colourful lives can shape their work in unexpected, sometimes thrilling ways.

Alcott’s own life bled into these tales. The governess in Behind a Mask seems to be borne out of her own brief stint as a governess, which she hated, and her time as a nurse during the Civil War clearly informed Perilous Play, where genteel friends casually experiment with hashish-laced bonbons. Her favourite authors included Charlotte Brontë, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller, perhaps giving her the Gothic grammar we see in so many of these stories.

But then Little Women came along and made her famous, neatly slotting her into the box of “the children’s friend.” Alcott mostly stopped writing her thrillers till A Modern Mephistopheles, published anonymously in 1877. It was a rare post-fame return to her “gorgeous fantasies.”

It wasn’t until the 1940s that Alcott’s double life was properly unearthed. Two book dealers and literary detectives – Madeleine Stern (the editor of Behind a Mask) and Leona Rostenberg – found references to AM Barnard in Alcott’s correspondence. They then tracked the stories down in old newspapers, confirmed the authorship, and brought them into print in the 1970s. That’s the very edition I found, decades later, in a bookshop halfway across the world.

And what a find.

Swati Daftuar is an independent journalist, editor, and literary curator. She is currently a Consulting Editor at Speaking Tiger Books and Literary Curator at Kunzum.