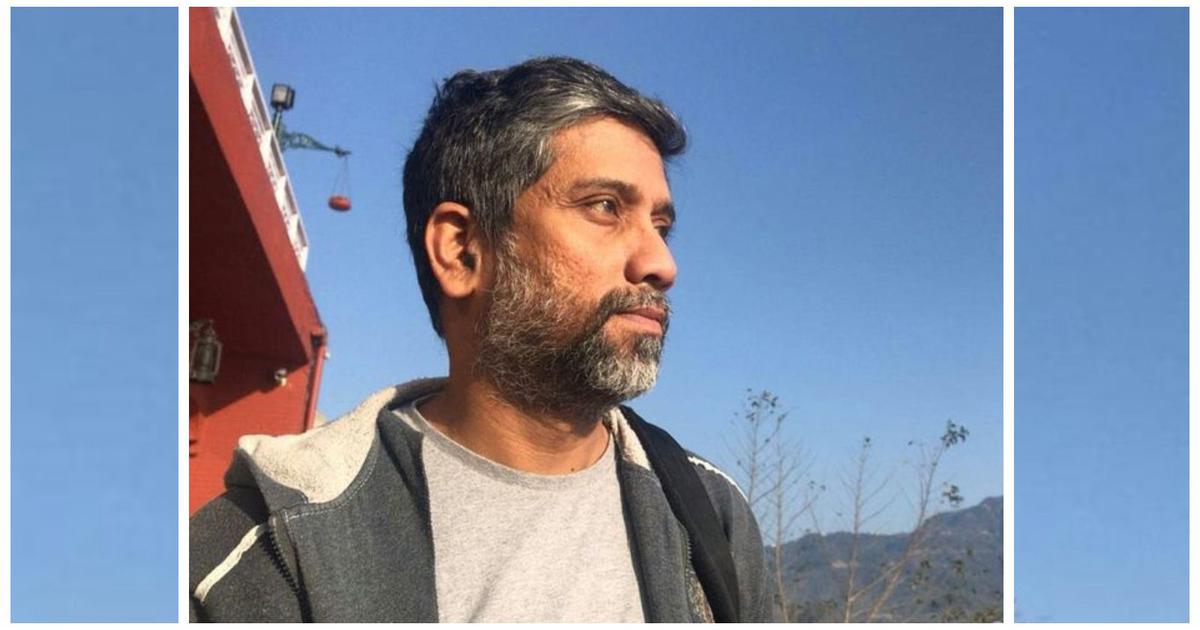

On July 28, Delhi University professor 51-year-old Hany Babu will complete five years of incarceration.

When the National Investigation Agency came for Babu in 2020, India was battling the Covid-19 virus, which is known to fester and multiply in densely packed spaces, such as prison cells.

Babu was soon infected by the virus, but his suffering was not limited to it. He subsequently contracted a serious eye infection for which he was hospitalised after his condition was reported to have deteriorated alarmingly.

At the time of his arrest, his daughter was 17 years old, and his mother – then in her late 70s – kept telling his wife, Jenny Rowena: “Go and tell the judge that Babu is a nice person. Tell the lawyer this, that Babu is a good person and he has done no crime. Tell them to let him out, his mother is waiting.”

But now, she has stopped saying this, Rowena, who is also a Delhi University professor, said in a phone call. “It’s been five years and she is not able to sleep,” Rowena added. “She is now in her 80s, has a lot of health issues and she just waits for that one phone call every week.”

‘She went numb’

Babu was among 16 people – activists, lawyers and professors – who were arrested under strict anti-terror laws in connection with caste violence at Bhima Koregaon near Pune in January 2018.

He was a member of a committee formed to defend GN Saibaba, a former Delhi University professor who had been sentenced to a life term for his alleged links to the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist).

The first batch of arrests in the Bhima Koregaon case took place in 2018. In the years that followed, others were arrested too.

Since then, independent investigators have found clues that allegedly show that the authorities have used fabricated evidence to build a case against the accused. Human rights organisations have described the case as a witch-hunt against political dissidents.

When Babu was arrested in 2020, their teenage daughter could not understand what had happened. She did not speak to anyone for the first three months after his arrest. “She went numb,” Rowena said.

The first time she visited her father in Taloja jail near Mumbai, they met in a small crowded shed. She suffered a sun stroke and contracted a fever.

Now 22, she is about to finish a degree in journalism. Every month the mother and daughter rattle down in a train from Delhi to Mumbai to meet Hany Babu either at the court or at Taloja jail.

Of the 16 people arrested in the Bhima Koregaon case, eight have been released on bail so far. One person, an octogenarian Jesuit priest, died while still in judicial custody.

Meetings with Babu

I asked Rowena what she and Babu talk about when they meet.

“We usually just discuss what he is reading and what I am reading,” Rowena said. It has been that way with them since the beginning: “That is how we became friends, also, and that’s how our relationship began.”

While Rowena feels happy when she is going to see Babu, the journey back from Mumbai is arduous. “Going is very nice,” she said. “But coming back is very bad. Most of the time I get a fever.”

The constraints of their lives – Rowena’s job and her daughter’s education – mean that they cannot spend too much time travelling to and from Maharashtra. So they take the train the evening before their visit and return right after.

“I am somewhat struggling to manage everything,” Rowena said.

‘What is the logic?’

What Rowena too does not understand is why Babu still needs to be in jail.

“Babu now completes five years in jail”, she said. “What is the logic of keeping people as undertrials for so long? At the same time, the prisons are overcrowded, and there is no facility for anyone there.”

According to the India Justice Report 2025, the national occupancy rate in prisons stands at 131%, with 76% of the prison population merely comprising people whose trials have not been completed – or are still waiting for proceedings to begin. In Maharashtra alone, the prison occupancy rate as of December 2022 was 161%.

“I think this is the punishment,” Rowena said. “They know that if they hold a trial, there is no case.”

Evidence questioned

Hany Babu and the 15 others in this case were booked under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, which makes obtaining bail very difficult.

However, independent experts have questioned the charges in this case and the credibility of the evidence cited to incarcerate the accused. In a 2023 book, Alpa Shah, a professor of social anthropology at Oxford, described how electronic devices and email accounts belonging to the accused may have been hacked in order to plant evidence.

She named Babu as being among those whose email accounts had allegedly been hacked. She also presented information to allege links between this hacking operation and those investigating the Bhima Koregaon case.

Babu’s computer had been seized in a raid on his home in September 2019 but he was neither summoned nor arrested until July 2020.

“If I ask them to tell me in a sentence what is Babu’s crime, what did he do, will they be able to tell me?” Rowena asked.

Costs and consequences of imprisonment

It takes several years before a UAPA case reaches its conclusion – and even then the conviction rate is very low. The government’s own data shows that of the total of 8,719 cases registered under the UAPA between 2014 and 2022, only 215 cases resulted in conviction; 567 were acquitted.

One of the accused in the case with Babu, Father Stan Swamy, died as an incarcerated undertrial in 2021, a day before his bail hearing. Swamy, 84, who had Parkinson’s disease, died a prisoner without ever being found guilty.

When Swamy passed away in Mumbai’s Holy Family Hospital, he had already told the court that his body functions had undergone a steady regression in jail and all he wanted to do was to go home.

But Indian jails are full of ailing prisoners. In 2024, the Bombay High Court reversed the conviction of former Delhi University professor Saibaba, wheelchair bound and 90% disabled, and five of his co-accused in another UAPA case. Babu had formed a committee to coordinate Saibaba’s legal defence.

Saibaba and the others had been convicted under UAPA by a sessions court in 2017 for allegedly having links with the banned Maoist party and sentenced to life imprisonment.

But by the time the High Court acquitted them and ordered their release, one of Saibaba’s co-accused, 33-year-old agricultural worker Pandu Narote, had been dead for 19 months already. He had reportedly contracted swine flu in jail.

Saibaba too passed away from post-surgery complications within months of his release, after suffering in jail for a decade. He was 57.

When asked about Babu’s health, Rowena said that he is suffering from a series of ailments: frozen shoulders, knee pain, high blood pressure and cataract. Despite this, and the fact that nearly five years have lapsed since his arrest and the trial is yet to begin, the courts have not demonstrated any desire to grant Babu his freedom.

On June 23, the Supreme Court refused to grant an urgent listing on Babu’s plea seeking a clarification on whether he could approach the Bombay High Court for bail. The apex court questioned the urgency of his plea. It said that the High Court had on May 2 sought this clarification from the Supreme Court but Babu’s counsel had not approached the Supreme Court before it shut for vacation on May 23.

Babu’s lawyer explained that the delay had occurred because certified copies of some documents were still being gathered. Nonetheless, the vacation bench of the Supreme Court asked him to come back when vacation ends in mid-July.

But it is not just Babu’s health that Rowena worries about. She recalled the ordeal of another person accused along with Babu, 38-year-old Mahesh Raut.

In September 2023, the Bombay High Court had granted bail to Raut, noting that the material against him does not lead to a prima facie inference of him having committed a terrorist act as defined under the UAPA. However, the High Court stayed its own order for three weeks to allow the National Investigation Agency time to appeal their decision. The Supreme Court then went on to extend the stay.

A year later, in September 2024, The Indian Express reported that the appeal had already come up for hearing 13 times in the Supreme Court. But the court has still not passed a verdict in the matter. Barring two brief spells, when Raut stepped out for his grandmother’s last rites in 2024 and to prepare for his LLB exams earlier this year, Raut has languished behind bars.

“And Mahesh is very sick,” Rowena tells me. “He has a lot of issues. His stomach is in a bad condition and he really can’t eat anything.”

Prisoner stories

But it isn’t just the accused in the Bhima Koregaon case whose plight Rowena laments.

“There are people in prison whose stories never come out,” she said. “They are not released when they are sick. They die in prison for want of adequate treatment. Many can’t pay their bail bonds so they are never released. There are a lot of Adivasis who don’t even have anyone to come to visit them. Whenever you write about us, you should also write about these people.”

Rowena is joined by her husband in her concern for other prisoners. Babu spends his time in jail teaching his fellow inmates English and helping many of them make sense of the legalese that defines the contours of their lives.

In his free time, Rowena said, he likes to write, even though his barrack is crowded, the TV is usually blaring and there is no table for him to sit and study. And even though he may be slowly losing vision in one eye from cataract.

In 2023, while in jail, Babu was awarded an honorary doctorate degree by Ghent University in Belgium. He was nominated for the honour as an acknowledgment of his efforts to safeguard the importance of academic freedom, language rights and equal access to education for minorities.

Meanwhile, Hany Babu’s octogenarian mother continues to quietly wait for her son to return home. Said Rowena, “She is literally getting tortured.”

Mekhala Saran is an independent journalist and researcher.