Let us not be coy. The limited war between Pakistan and India this past May, not long after the end-April terror attack near Pahalgam in Kashmir, has unlimited consequences for South Asia.

As we know, avionics, strike and defensive systems got a massive workout. Vulnerabilities and strengths were duly exploited. And, duly noted – including artfully minimised losses in aircraft, equipment, facilities, and personnel – by both countries, their defense suppliers and strategic partners, and the world at large. Drone warfare truly joined the destructive drone of warfare by “social” media, manned by keyboard warriors of South Asia.

Ceasefire has now lapsed into uneasy détente. Leaders of India and Pakistan have moved on from claiming victory for their domestic audiences – while the leader of the United States as typically claimed the victory as his. We in South Asia are urged to take a deep breath and carry on.

That is where the consequences enter, now brought to sharp relief by this on-again off-again conflict seemingly without end.

If we were to telescope to India’s security perspective – the perspective of a country that, significantly, shares borders with both China and all South Asian countries except Sri Lanka and the Maldives – the steady-state tandem enmity of Pakistan and China is joined by Bangladesh. This is being disseminated as an unholy triad, if you will, that carries both potential and demonstrable ill-will towards India.

Indeed, India’s newly voluble Chief of Defense Staff General Anil Chauhan indicated as much on July 8 at an event at a major establishment-oriented New Delhi think-tank. “There is a possible convergence of interest we can talk about between China, Pakistan and Bangladesh,” said Gen Chauhan during an address at Observer Research Foundation, “that may have implications for India’s stability and security dynamics”.

There are reasons for this and all of them, to India’s mind, are collectively a clear and present – and future – danger.

A dominant narrative in India is predicated on the South Asian ring of fire that its neighbours would be naïve to discount. Equally, India needs to accept that, while its regional strategic flex remains, its presumptuous South Asian zamindari, driven by sheer size and the geographic reality that no other South Asian country shares a land border with any other South Asian country but India, is over.

Let us pan this out.

Repeated calls for “destroying” Pakistan – mainly by India’s establishment-fed media and ruling party bots – is akin to Fool’s Gold. This goes beyond the silliness of Indian government officials claiming that turning off the tap of the Indus will bring Pakistan to its knees.

A fractured Pakistan will be a nightmare for India even though there are those among establishment hawks who see in such an eventuality the reclamation of all Kashmir. Add nuclear capability to that fracture and the future becomes a full-blown catastrophe that India’s ultra-Right ecosystem nurtured with disinformation, delusion, and social media strategy masquerading as security imperatives can scarcely comprehend.

Visualise generals as warlords. Visualise any number of fractious ethnic and religious groups in Pakistan which would sooner see any attack against India as a mark of faith and fulfilment. Visualise a future post-Pakistan’s poverty-stricken millions sloshing about in a fractured land; and consider if any border security in the world is robust enough to withstand a flight of such dismantled people.

The upshot: India will have to get its governance and hearts-and-minds act together in Kashmir, the same as Pakistan in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, if either is to withstand the other’s rhetorical and actual onslaughts. (Besides, Pakistan needs to get its act together in its massively restive and deliberately under-developed Balochistan province, among other regions.)

Over at the eastern arc, India’s goodwill had already begun to take a hit in Bangladesh, as public opinion saw India as standing with an increasingly corrupt, electorally wayward, and essentially dictatorial Awami League government led by former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, especially during the past decade.

India massively depleted its goodwill in a post-Hasina Bangladesh by standing with a belligerent Sheikh Hasina throughout the political upheaval over July and August 2024. And then, by presenting to outraged Bangladeshi citizenry the diplomatic horror of having India’s national security advisor welcome an ejected Hasina at Hindon air force base near Delhi on August 5 – on live television.

It was an optics disaster of epic proportion in both the mind’s eye of Bangladeshi citizenry and to the emotionally charged and mission-oriented housecleaners of Bangladesh’s interim government.

It’s a disaster from which India is yet to fully recover. It has made India’s strategic and economic interests in Bangladesh, transhipment to its entire northeastern region, and India’s strategic Siliguri Corridor deeply vulnerable to Bangladeshi policy squeeze. The risk of a squeeze by proxy makes matters worse for India: that slim corridor, the so-called Chicken’s Neck, is a short hop for a China nestled in the hotly contested Doklam region just to the north.

And for all of Bangladesh’s justified moral lament for the democratic dislocation of the Hasina years and the atrocities perpetrated against students and innocent citizens over July-August 2024 – which this columnist observed first-hand – its interim government isn’t blameless in adding to the tension.

For his part, the head of the interim government of Bangladesh, no slouch when it comes to a networking opportunity polished by a lifetime of limelight, put several words out of place during an official visit to China this past March. Among other things, he publicly marketed Bangladesh to Chinese officials and businesses as being China’s entrepôt for a “landlocked” northeastern India.

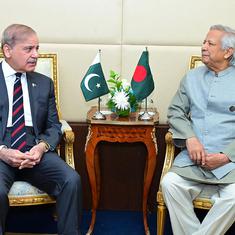

That too was an optics disaster – an observation which several senior South Asian diplomats have shared with me. With India’s ongoing border spat with China, and repeated announcements by various Bangladesh entities to offer Chinese interests a deal to develop the Teesta River basin in northern Bangladesh – close to the strategic hotspot of the Siliguri Corridor – it was akin to waving a red flag to a bull in a China shop. This came in addition to the visible thaw in Bangladesh-Pakistan relations in the post-Hasina era, another huge red flag for India, among several other factors, including the release from jail of several people India views as inimical to its security.

Bangladesh’s interim government walked back the China-in-Northeastern India talk, but the damage was done. I’ve heard career-officials gripe about how the interim government should realise its interim nature, scale back knee-jerk pronouncements and Goebbelsian spin, and permit regime-agnostic professionals to go about their business in Bangladesh’s national interest.

In a tit-for-tat response that one could term Pakistanesque – or Indiaesque, depending on the lens – India has begun to squeeze Bangladesh by withdrawing some trading and transhipment benefits. Citing quite legitimate security reasons India has also refrained from expanding visa issuance for Bangladeshi visitors to the peak-Hasina level of a staggering 1.6 million visas a year – the figure for 2023.

There are other indications of this avoidable freeze.

With its heightened threat perception and what it perceives as necessary maritime deterrence, enhanced Indian naval and security activity in both the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea has become the new constant.

There is the west-to-east arc of Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Myanmar – where China has displayed deft management to secure its energy, mineral, and territorial interests. From a regional-and-maritime perspective, Sri Lanka is of course another competitive geography for India and China and which, much like its southern co-location with neighbouring Maldives, completes the ring of encirclement for India.

There are several instances of the China and India’s push-and-shove in Sri Lanka, Maldives, Nepal, Myanmar, and, increasingly, Bangladesh, that this column has variously discussed over the past three years. But just how acute regional threat perception has become is indicated by a churlish incident from early this year – predating the India-Pakistan fracas in May.

A Bangladeshi naval vessel was to visit Colombo port for a courtesy call, en route Karachi for a naval exercise – Bangladeshi navy ships had earlier participated in previous editions of the exercise. From available indications, India pressured Sri Lanka to deny the vessel entry. It was touch and go for a while, but the Bangladesh-Sri Lanka “bilateral” prevailed.

Or, from India’s freshly jaundiced eye, the Pakistan-Bangladesh-Sri Lanka “trilateral”. Or to be a bit more provocative, perhaps the China-Pakistan-Bangladesh-Sri Lanka “quadrilateral” – that would, ironically, run counter to the Quad or Quadrilateral Security Dialogue between India, Japan, Australia, and the United States that is commonly perceived as a strategy to contain China in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region.

But for all that, there is monumental work to be done to mend the India-Bangladesh bilateral, a rent in which could – with or without China – ruin Eastern South Asia.

Sudeep Chakravarti works in the policy-and-practice space in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Region.

This article was first published on Dhaka Tribune.