Jeet Thayil’s genre-blending “documentary novel”, The Elsewhereans, begins with a meet-cute. The year is 1957. Ammu Thomas, winner of 27 medals and 25 cups in school athletic championships, now teaches physics, chemistry, and biology at a high school in Alwaye, Kerala. Thayil Jacob Sony George is a journalist in Bombay, working for The Free Press Journal. Their families have met. Marriage has been proposed. In a break from convention, George decides to meet Ammu, scandalously unchaperoned. Swiftly, in a move familiar to Thayil’s long-time readers, the author defies audience expectations, and what follows is not a romance but the chronicle of a marriage that is complex and often messy, a family memoir, a travel diary, an extensive documentation of socio-cultural imperatives, all layered within a narrative of grief, loss, and displacement.

Embracing disruption

With Ammu and George, and a cast of family members who appear and disappear through the text, the narrative travels across continents and decades, reaching back and forth in memory and re-constructing events through documents like letters, photographs, postcards, and fragments of notes. Lest we fall into the trap of reading the text autobiographically, an unpardonable breach of readerly etiquette in a post-truth, post-postmodern world, Thayil reminds us, gently, “The real names and photographs in these pages are fictions. The fictional names and events are documentary. The truth, as we know, lies in between.”

“Elsewhere” is a construct, as political as it is cultural, that steps away from the trauma inherent in displacement (as seen in much of diasporic writing and theorisation) and embraces disruption. Ammu and George’s peripatetic lifestyle takes them from the young bride’s family home, Anniethottam in Kerala, to a small, shared apartment in Mahim in Bombay, and thenceforth to provincial Patna of the 1960s, in the grip of student agitations, followed by the cultural conflict and fraught racism of Hong Kong, the harsh aftermath of the war in Vietnam, and routing through Bombay and New York, lands at Bangalore, where they are forced into a lockdown during the pandemic of 2020. They become Elsewhereans who do not belong to any one place, whose home is an unmoored, shifting space, that defies rootedness.

In Hong Kong, where everyone is from somewhere else, Ammu experiences Elsewhere “as a spiritual calling” and begins to see “internationalism as the true nationalism and freedom as the only patriotism.” This unmooring from the normativity of a fixed, unalienable “home” and the felicity with which it is transformed into something mutable is what makes the text and its inhabitants unusual. It also captures the multi-lingual/ multi-ethnic/ multi-cultural milieu of many of its readers, for whom leaving “home” is no longer defined by a hybrid duality.

The book’s primary narratorial voice belongs to Jeet, the son of Ammu and George, named rather infrequently, despite a significant presence in the narrative. As much of an Elsewherean as his parents, while also caught in that most banal of power dynamics – the father-son conflict, Jeet finds himself retracing the trajectory of journeys already undertaken. He goes to Hong Kong to work for the Asia-centric magazine initiated by his father, re-lives his father’s journey in Vietnam, in search of the woman in a photograph he finds in his father’s documents, and travels to Paris to visit Baudelaire’s grave in a re-tracing of his Uncle Markose’s lifelong dedication to the works of the French poet. Jeet insists he is a migrant, not an immigrant, reiterating the difference between someone who wants to make home afresh in a new location and someone whose home moves with them, affecting no need for permanence. He is not the only one choosing a life of continual transit.

In a church in Dessie, Ethiopia, Uma, Ammu’s sister-in-law, finds a portrait of Mary, Joseph and Jesus, dark-skinned like her, and recognizes in them the aura of Elsewhere: “Mary and Joseph were migrants when Jesus was born, and for years afterwards. Jesus was a migrant. His family went from one place to another to stay alive. Movement. Movement is God’s message”. Early in the book, George points to the centrality of the same sort of movement in the Indian epics as well – in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Elsewhere, then, becomes the human condition for those who subvert stasis, for whom “home is anywhere but here”, whether voluntarily or under coercion.

Places and contexts

Recent shifts in geopolitics have brought us to a point where history itself has become suspect, subject to constant revisioning, elisions and erasure by governments and systems of education. Fiction and memoirs seem to have nimbly stepped into the gaps that appear in official accounts and textbooks, such that more history – cultural, social, political and personal – is being told in the interstices between fiction and non-fiction than in classrooms and public discourse. The Elsewhereans firmly situates itself within this space where the accounts of the people in its pages also become accounts of the places and contexts they emerge from.

When Ammu is in what looks like interminable labour at Anniethottam, there are protest rallies being organised across the state against the Namboodiripad government by anti-communist church organisations allied with the Congress party, the reader learns, getting a minor lesson in the turbulent politics of the state. Da Nang, Jeet’s guide during his visit to Vietnam, structures her “sightseeing” plan to bring alive the history of the war – its horrors, its violence, and the pushback of the Vietnamese people – to tourists who are left questioning their certainties. State control in China and the fallout of the Cultural Revolution are brought home in vivid detail in the narrator’s conversations with Lijia, a photographer and documentarian whose father was penalised for his seemingly radical poetry and came perilously close to being executed as a political prisoner. Thayil writes of encounters with racism and the debilitating politics of hyper-nationalism that uses language and linguistic difference as tools of oppression. “To know history is to know loss, and the displaced know it best”, he writes, and the text stands testimony to its truth.

In calling this a “documentary novel”, Thayil pushes the boundaries of both genres, incorporating visual, visceral elements in his narrative while disregarding the rules of plot and temporality. Re-constructing memory through material documents and in storytelling, the book travels through timelines, connecting places and events in a manner as itinerant as its characters are. It is the Elsewhereans, people who cannot be assigned a singular location or identity, that give the book its raison d’être, pulling the reader, almost voyeuristically, into the everyday concerns, anxieties, and triumphs of Thayil’s characters.

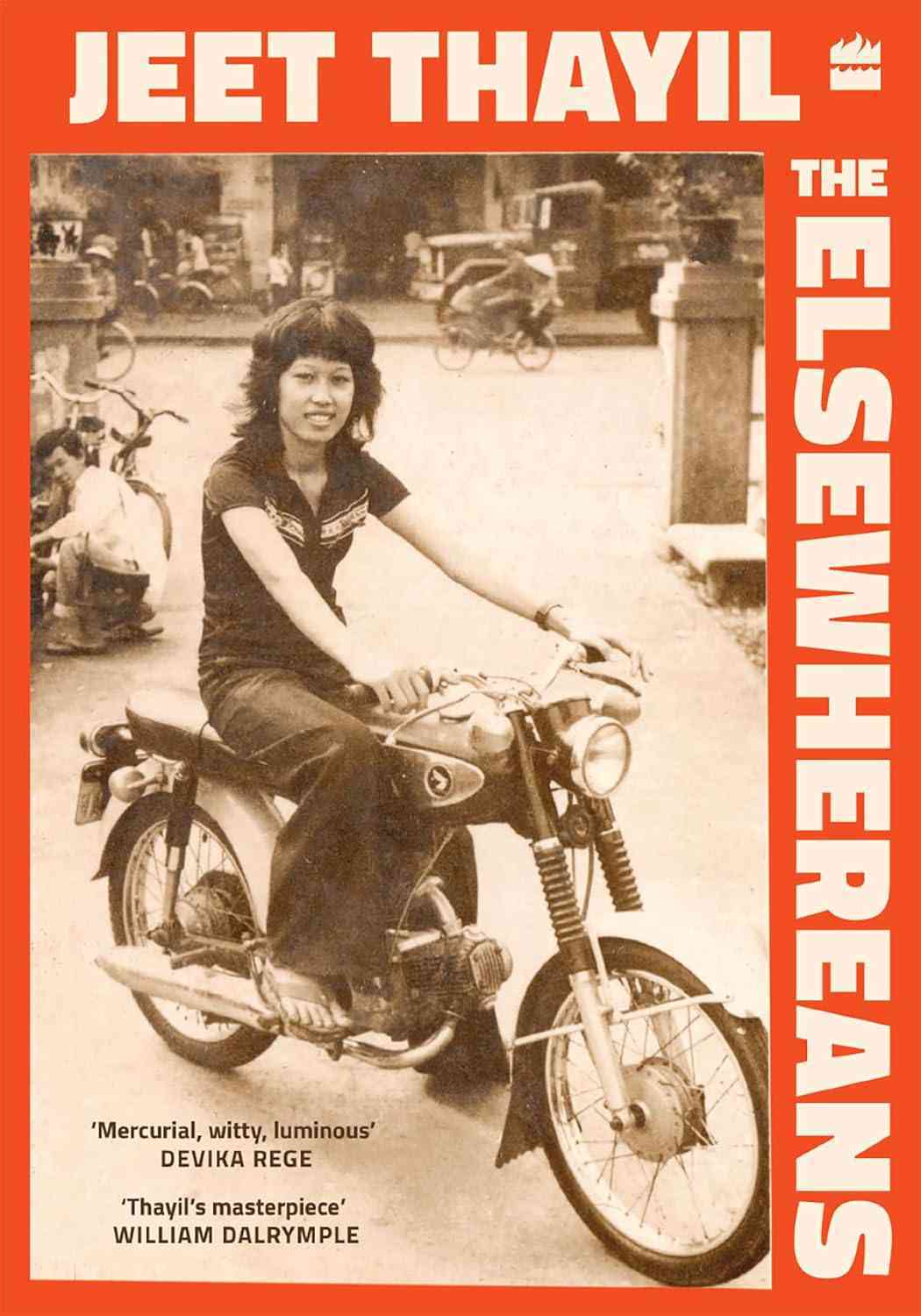

At Ammu and George’s wedding, we are introduced to Thommen, a wedding chef “famous for his bad temper and his red meen curry”. It is to Thayil’s credit that the force of Thommen’s personality lingers in the reader’s memory just as much as the spectral taste of his feast lingers on the palate. The “opiated midwife” who attends to Ammu has a string of legends that follow in her wake and is also a conduit into the history of the opium trade and colonisation in Asia. Then, there are the rule-breaking women – Nguyen Phuc Chau, immortalised in a black-and-white photograph of the woman on a motorcycle, responsible for keeping George alive during his time in Vietnam; her granddaughter, Da Nang, who named herself after her father’s hometown, a major site of battle during the Vietnam War; and Chachiamma, Jeet’s cousin who chose herself over social obligations. These Elsewhereans weave in and out of each other’s stories, constructing a complex structure that needs the reader’s participation to come together as a whole.

Unusually, for Thayil’s incisive writing, at the core of The Elsewhereans is a delicate handling of complex emotions. Grief, frustration, joy, and love all play across the relationships of our Elsewhereans. Ammu’s assumption of marital responsibilities that George had started to shed from the very beginning of their marriage sets in motion a critique of marriage and patriarchal oppression that turns darker with other relationships, other marriages in the narrative, leading to the insipid conclusion that women who resent their husbands do not often leave them. Until they do. The breakdown of communication between fathers and sons, the inability to accommodate difference, and relationships caught in the liminality of love and resentment is another thing the narrative captures, without any drama, any cloying sentimentality. Its understated response to grief- stemming from the loss of home or a beloved or oneself – is as heartbreaking as it is compelling.

Thayil takes the affect of grief and ties it to an ongoing project of social mirroring. Alongside a young Jeet, the reader must learn that “the dead did not return. Their peculiarities fade first, then their faces and last of all their voices.” “In time”, Markose tells him, “you’ll find that our forgetfulness about death and a hundred other things, for example, the keeping of slaves, the contempt for people of darker races and castes, the belief in godmen, the denial of equality, fraternity and liberty, all this is not the sole prerogative of Indians.” Did grieving just turn political? You might need an Elsewherean to confirm.

The Elsewhereans: A Documentary Novel, Jeet Thayil, HarperCollins India.