For decades, New Delhi has been the seat of grand ambitions.

LK Advani was sent to the Lok Sabha from here, as was Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The Bharatiya Janata Party's Delhi doyen Jagmohan turned it into a stronghold. It is the central portion of this constituency that gave the Aam Aadmi Party its signature victory in the Delhi state elections last December, as Arvind Kejriwal defeated three-time chief minister Sheila Dikshit by 25,000 votes. It was also the site of Kejriwal's most famous protests. And it is here that AAP could end up suffering its most serious Lok Sabha setback.

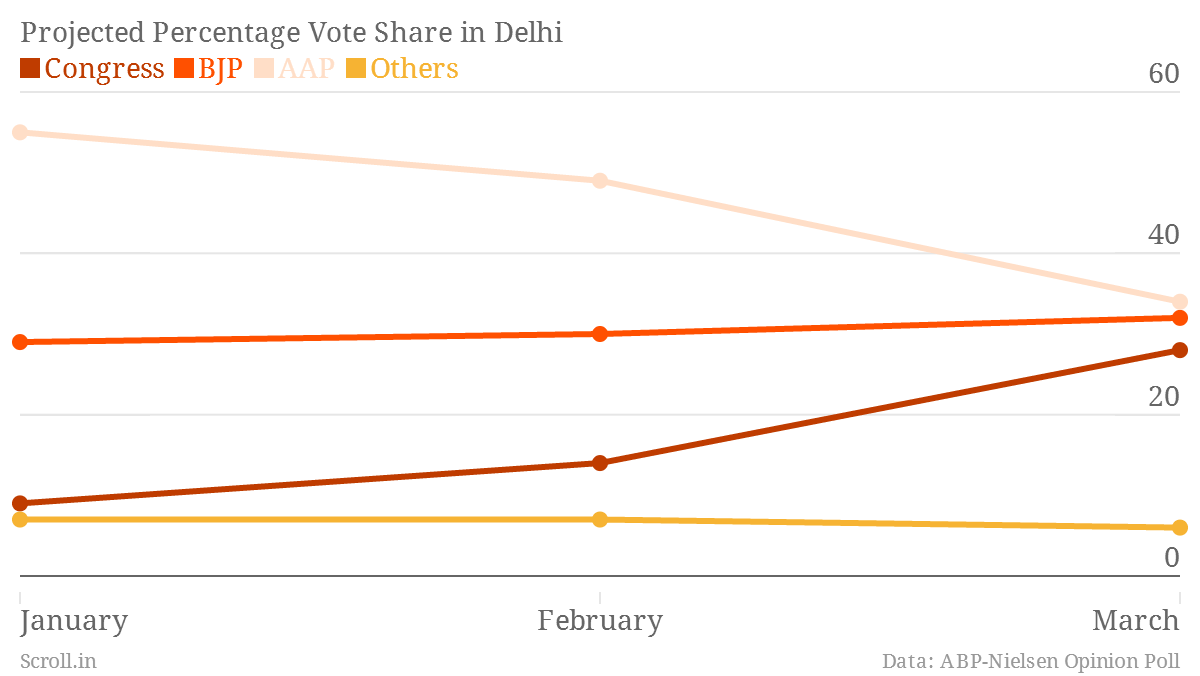

Recent polls suggest that the party that stunned the country in the Assembly elections last year has been steadily losing support ever since Kejriwal resigned as chief minister. An ABP-Nielsen poll saw AAP’s vote share come down from 55 per cent in January to just 34 per cent in March. (For the record, ABP-Nielsen predicted 28 per cent vote share for AAP in the Delhi Assembly elections last year, with the final tally coming to 29.4 per cent. Their seat predictions, as with those of most other pollsters however, were wildly off target).

Those votes aren't being absorbed into the Modi Wave. They're going back to where they came from: the Congress. Despite having been trounced in December, Congress saw a bounce from just 9 per cent of the projected votes in the January poll to 28 per cent in March. Nowhere is this jhaadu-haath back-and-forth more evident than in the New Delhi constituency, where AAP managed to win seven of the 10 Assembly seats last year.

"See, we have never gone with the BJP, and we never will," said Meena Chhetri, a housewife from Sewa Nagar. "Actually we have always been with the haath (Congress), until last time, when I pressed the button for Kejriwal." As it turned out, Chhetri happened to be saying this at a Congress rally, where she had only come to get her photo taken with the party President Sonia Gandhi. “I want to see her, because I’ve voted for her all my life. And I think now I will have to go back to her this time, instead of Kejriwal.”

Chhetri is like many other longtime Congress hands who put their trust in Kejriwal, but could easily switch their allegiance back to the Grand Old Party for the coming elections. That means journalist Ashish Khetan, who was picked ahead of bigger AAP names to fight from this iconic seat, will have to do his best to fend off the accusation that has dogged his party every since Kejriwal resigned as chief minister: that they “ran away” from the Delhi government.

“They say we disappeared, we ran away,” Khetan told a mostly indifferent audience at a jansabha in New Moti Nagar. “I asked them, people usually take something and run, no? What did we steal?”

That’s not answer enough for Inquilab, an unemployed elderly man who campaigned for AAP last December. As far as he is concerned, if AAP has left once, it can do so again. “I’m still thinking of voting for them, but what happens if my vote gets wasted?” he asked.

To most people, the New Delhi seat is thought to be populated primarily by government servants. As he takes his campaign around town, it’s clear that Ajay Maken, the two-time Congress incumbent, is aiming squarely at this audience. Even in the rain, a hefty crowd of Congress workers is always accompanying Maken to yell out slogans about his efforts in setting up the Seventh Pay Commission, in endorsing One Rank One Pension and increasing dearness allowance.

Those measures, as well as a relatively untarnished image and a noted pedigree — Maken’s uncle was a massively popular union leader and MP who was assassinated in 1985 — make him the Congress’ best hope in Delhi, and an obvious chief ministerial candidate whenever the capital has Assembly elections.

But New Delhi is much more than just government employees and the salaried class. “All that they are saying sounds good,” said Ramlal, as Maken’s padyatra rolls through a colony in Manakpura, “but what has he done in 10 years about the sewage that keeps filling the streets?”

Indeed, the larger Lok Sabha constituency, which covers nine other Assembly seats beyond the one Kejriwal famously won, also has plenty of low-cost housing and slums. They are home to people who voted overwhelmingly for AAP in December.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidate, Meenakshi Lekhi — most famous for getting a dressing down from Times Now’s Arnab Goswami — can expect to grab votes in the richer areas where her party picked up Assembly seats. Even in some of the poorer localities, the younger voters might want to be a part of the "Modi wave".

“We gave the jhaaduwala (Kejriwal) a chance, so now lets give Modi also a turn,” said Prince, a young man in a slum in Aram Bagh, even as his mother said their family will go back to the Congress. Even after Lekhi passed through Prince’s jhuggi, he insisted he wouldn’t be voting for “some BJP woman” who had turned up. “I want Modi to be the Prime Minister.”

But Lekhi, who like Khetan was also given the important ticket over more popular names like Subramanian Swamy and Nirmala Seetharaman, will get her biggest boost from voters for whom the anti-Congress fervour of December has given way to uncertainty about the Aam Aadmi Party.

“They said a lot and even did some good things, people could go to the hospital, we hoped for electricity,” said Vijaya, who runs a paan-stand in New Moti Nagar. “But who knows, tomorrow they might go away. The Congress will always be there for us poor, for better or for worse.”