Watsa, perhaps better known today for his newspaper column dispensing often wry advice on sex, was also the first to push for the inclusion of sex education in the FPAI’s programmes in the late 1970s.

“You need to have special classes for parents,” he said. “Parents should be the ones who should be involved deeply, but they pass the job on to teachers.” But teachers, he said, do not take an active part in sex education for fear of being criticised by both parents and politicians.

This fear might partly stem from the pronouncements of political leaders. In the latest instance, last month, health minister Harsh Vardhan, a qualified doctor, advocated the Gandhian route to birth control through abstinence and yoga and said that sex education in its current form should not be taught in schools. He later clarified that he was only against graphical representation of what he termed “vulgarity".

But his remarks have yet again underlined the political class's confused and often misguided approach to sex education.

In contrast, over the years, the focus of the FPAI, which was founded in 1949, has expanded from issues of fertility and controlling the number of children a healthy family should have to the rights of young people in accessing information and knowledge about their sexuality.

It also works closely with the government to promote the reproductive health of women, including helping to plan and pace their pregnancies. This is significant in a country where women are having fewer children than before but still face potentially fatal health risks before and after pregnancy.

Yet even the FPAI's founders, Dhanvanthi Rama Rau and Avabai Wadia, among other women’s welfare activists, had concerns when pondering contraception and family planning.

“The first time I heard the words ‘birth control’ I was revolted,” Wadia wrote in her memoir, The Light is Ours. “Was it natural, was it ethical, was it moral, was it healthy, did it encourage selfishness, promiscuity, salacity?”

She finally reasoned that if women were not allowed to decide how many children they had and at what pace, they would not be able to make healthy decisions about their lives. This, she wrote, was more pressing than ethical concerns about controlling births.

She continued to prioritise sex education even in later life. When in the 1970s Watsa pushed for the inclusion of sex education in FPAI work, he was at first hesitant to broach the topic with Wadia.

“He thought that because she was senior, she would have reservations,” said RP Soonawala, a gynaecologist and consultant with the FPAI, who developed a plastic intra-uterine device that is still in use today. “But the moment she understood the need for it, she was the first person to push for it.”

The FPAI was not the first or even the only effort to introduce family planning to India. India’s first birth control clinic, run clandestinely by a mathematics professor RD Karve, opened in Bombay in 1921. Karve kept no records of his patients in order to preserve their privacy, but he was among the first to introduce diaphragms and cervical caps as contraceptive methods in India.

Almost ten years later, the Maharajah of Mysore opened the first government-sponsored birth control clinics in the world, in Bangalore and Mysore in 1930.

By the time Independence came, Rama Rau and Wadia managed to convince Jawaharlal Nehru to include family planning in the first five-year plan.

Apart from a few brief years in the 1970s when the government aggressively pursued family planning and male sterilisation under Sanjay Gandhi’s direction, female-oriented contraception remains the more preferred form. Today, more women actively pursue contraception than men.

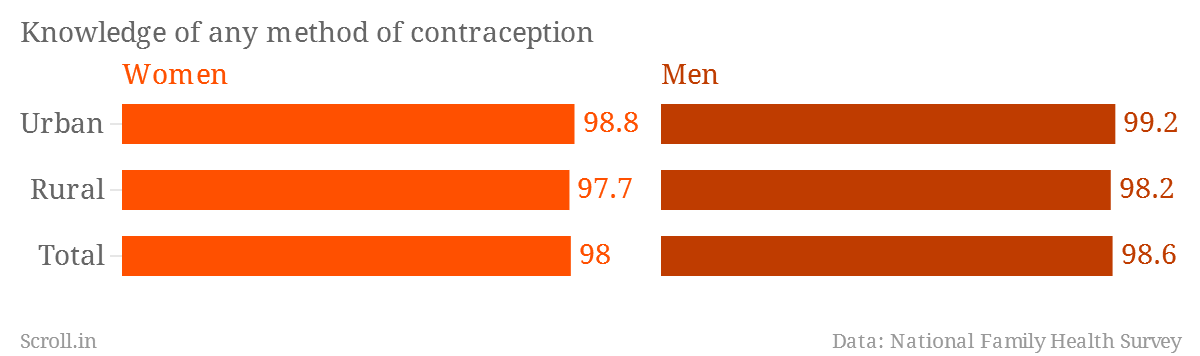

But knowledge about contraception does not always lead to using it. In the 2004-05 National Family Health Survey, of which there have only been three since 1992, almost 100% of respondents said they knew about some form of birth control, whether traditional, such as the controlled withdrawal of the penis before ejaculation and synchronising sex with periods of low fertility in the menstrual cycle or modern intra-uterine devices, condoms and birth control pills. This is not, however, matched in usage patterns.

“If people had sex education, they would have better information about abortion,” said Usha Krishna, another former FPAI president. “If they knew more about how, when and where to get abortions, we could theoretically bring abortion deaths to nil.”