Rashid Vally is one of those. An Asian whose family operated a small general store in Cape Town, Vally attended the Central Indian High School, set up by the Indian Congress partly in response to the introduction of the Group Areas Act in 1950. His father opened a small café, which just happened to be below the law offices of Nelson Mandela. The future President of South Africa was a regular customer, as were many other leading lights of the country's political and cultural world.

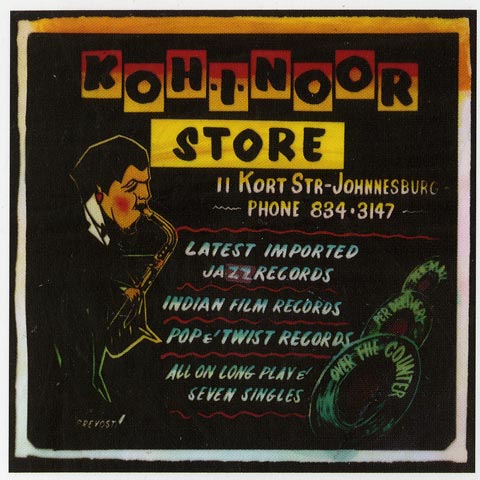

To indulge his son’s passion for music, Vally’s father allowed the boy to set up a small section where he sold and played jazz records from America. When he wasn’t off delivering groceries to his father’s customers, he became known as the kid who loved jazz. Eventually, his passion so consumed young Rashid that he began ordering records wholesale from the US; the café was transformed into Kohinoor Records, which exists even now.

Kohinoor and Vally became well known in the vibrant Cape Town music scene and Vally set up a record label, Soultown, to promote the music of local artists. One day, a slender handsome man walked into Kohinoor and approached Vally. He said he had heard of his Soultown recordings and that they were good. "Would you record me," the man asked. The man was Dollar Brand (later known as Abdullah Ibrahim), who would go on to become South Africa's most prominent jazz export. There began one of the most enduring relationships in South African music, with Vally releasing a whole series of records by Ibrahim and other outstanding musicians.

Ibrahim had a karate studio which he called As Shams (The Sun). Vally and Ibrahim agreed to call Rashid’s new label As Shams and had his brother-in-law design the now iconic label. Like the Sun Records on the other side of the world, in Memphis, Tennessee, Vally’s label played an absolutely crucial role in the development and preservation of South African jazz and popular music.

The late '60s and early '70s were terrible years for non-white South Africans. Recording music was a challenge as it was constantly interfered with by the authorities who were hypersensitive to any title or artist who was deemed to be hiding political messages in their music. Vally recalls how difficult it was in those years, when he would often have to work late at night, travel to the townships surround Cape Town and bring artists to the studio to record. Unlike other producers who seemed to be only concerned in the monetary value of a hit, Rashid Vally was always a deep lover of the music. He imposed no restrictions on the artists and was ready to link up with other bigger distributors to get the music out into the public.

It is hard to overestimate the role Vally has played in South African music. The list of artists (Pop Mohammad, Ibrahim, Bea Benjamin, Basil Coetzee just to name a few) and classic albums he has produced and distributed through his label stretches belief. The atmosphere and environment he created in the very dark days of apartheid, both in the studio and his humanity, are a contribution South Asians should not only be familiar with but take deep pride in.

The following clips review just a handful of the many classic and towering tracks Rashid Vally and As Shams Records had a hand in delivering to the world.

Abdullah Ibrahim aka Dollar Brand

Mannenberg

Mannenberg, the Soweto of Cape Town, was the township to which many thousands of people were moved from District 6 in the central part of the city after the enactment of the Group Areas Act which forcibly removed non-whites from the more developed parts of urban areas. The tune was recorded on an upright piano with tacks on the hammers to give it special tinny sound. An iconic song and melody, and probably one of the most seminal pieces in South African jazz, this was recorded in Cape Town and released on Vally’s As Shams label. The title of the song came to Ibrahim spontaneously, as it seemed to sum up the mood at the time. It was an instant hit, selling 50,000 copies in six months and becoming a sort of anti-apartheid anthem. According to Vally, “The youth in the township used to put words to the tune and it soon became a struggle song. Basil Coetzee and Robbie Jansen played it at almost all the UDF [United Democratic Front] rallies around the country.”

The track was also smuggled into Mandela’s prison cell on Robin Island, to be the first contact with music that Madiba had had for many years.

Bea Benjamin

Music

Bea Benjamin was a dedicated jazz musician, unrelenting in her commitment to spirit and music. She married Abdullah Ibrahim and moved into self-exile in Europe and New York in 1962. In Zurich, she and Ibrahim met Duke Ellington who not only championed Ibrahim but also arranged for Benjamin to sing with his orchestra, including at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1965. Ellington, in fact, asked her to join his band permanently but the challenges of managing Ibrahim’s career and raising children forced her to decline. In 1976, she returned to South Africa and recorded African Songbird, from which this moody evocative track in taken. Vally produced this masterpiece and released it on As Shams.

Dick Khoza

Chapita

Dick Khoza, a drummer, was from Malawi originally. But like so many others from the surrounding southern African countries found himself in South Africa seeking an opportunity and outlet for his creative energy. In the 1950s and '60s he played with many South African musicians including Dudu Pakwana and Tete Mbambisa. In 1976, after the Soweto uprising, Khoza took a band into the studio and recorded Chapita, a monument to African funk. As Vally recalls, “the labels at that time were uninterested in jazz, just looking for a hit. I gave musicians complete freedom.”

The Beaters

Harari

The Beaters were South Africa’s first black rock ‘n roll band and toured extensively throughout the region. They had a particularly loyal fan base in neighbouring Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and eventually changed their name from the Beaters to Harari, in honour of the township around the capital of Salisbury. Of course, after independence in 1980, Harare was declared the capital of Zimbabwe. This cut is a sublime slice of '70s funk (with echoes for WAR) and the standout song of this pioneering band.

Richard ‘Groove’ Holmes

Killer Joe

Richard Holmes was one of America’s great ambassadors of the Hammond B3 organ, who along with Jimmy McGriff and Jimmy Smith did so much to popularise the instrument in jazz and funk. A politically minded musician, Holmes travelled to apartheid South Africa in violation of the cultural boycott to record an album with South African jazzmen, including Pops Mohamed, called African Encounter. An obscure and rare recording, it was nevertheless As Shams (again) that released it!