They were the first of migration that would eventually number around 15 lakh contract workers from Asia, Africa and the South Pacific to travel across the world to work in European colonies around the world. The majority of these were Indians.

One hundred and eighty years later, foreign minister Sushma Swaraj is in Mauritius for an international conference to commemorate this event. The conference, which ends today, will flag off the International Indentured Labour Route project, funded by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, which will expand the research network in the 22 countries where indentured labourers worked.

Ironically, the harsh system of indentured labour was a result of the movement to abolish slavery. The British were the first European power to ban slavery in 1833. They were followed by France in 1848 and the Netherlands in 1863. All soon realised that abolishing slavery had immediate repercussions on their supplies of labour, especially on plantations. Worker signed contracts, often for five years, to work abroad for specified wage.

The first load of workers who alighted at Mauritius were a part of the “great experiment” as the British called it, and after its success, other colonial powers followed suit.

Most girmitiyas ‒ as people who signed these girmits, or agreements, came to be known ‒ were attempting to escape dire conditions of debt and famine in India. They arrived in such large numbers across the 19th century that even today, their descendants form significant proportions of such former plantation colonies as Guyana, Trinidad, Surinam and Mauritius.

For the first 30 years, the British even maintained the pretence that this was not a marginally better form of slavery by promising free passage back to all labourers at the end of their contract. In 1861, they abolished this clause to deter people from returning home.

The British government finally abolished the system of indentured labour in 1917 after a sustained movement against it. It then spent several years repatriating those who still wanted to return to their native countries. The last ship with repatriates from the West Indies docked in India in 1954. In 2006, UNESCO declared Aapravasi Ghat in Mauritius a world heritage site.

The following photographs, sourced from Creative Commons, show the lives of Indian expatriates in foreign lands.

Indentured workers in Mauritius.

Newly arrived Indian workers in Trinidad.

East Indians in Trinidad.

British Indians in Surinam celebrating Tajiya.

Girmitiyas in Fiji.

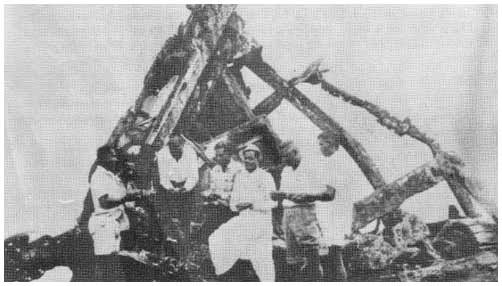

Wreck of the Syria, the first ship with Indian workers to travel to Fiji.

Indian workers in Réunion.

![[Photos] 180 years on, India commemorates the first indentured labourers to go to Mauritius](https://sc0.blr1.digitaloceanspaces.com/large/686698-4ab58b04-1545-4836-99aa-4d10943a36ad.jpg)