The study collated data of critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable species listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and found that amphibians fare the worst. Among the union’s list are several Indian species.

Even more disconcertingly, the Nature study figures necessarily lists only the species that are already known. There continue to be unexplored habitats with unknown species, whose numbers are estimated to range between two million and over 50 million. Many of these uncatalogued species are being destroyed even before we find them.

Taking these factors into account, the study estimates that earth is losing 0.01% to 0.7% of its species every year. If the rate of 0.7% is sustained, thousands of species would die out annually, leading to a mass extinction – a loss of 75% of species – over the next couple of centuries.

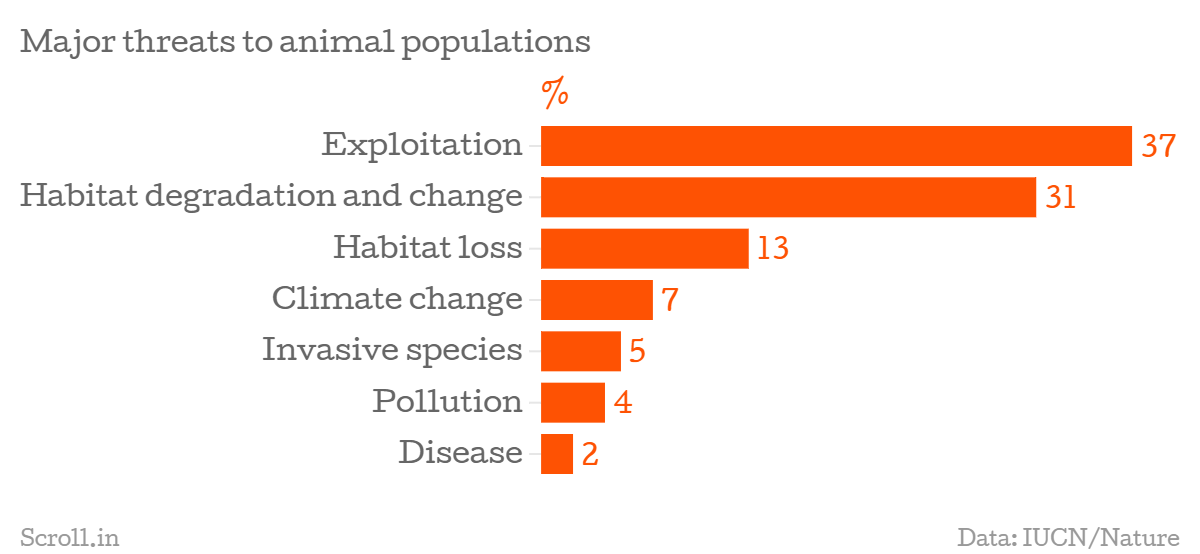

This mass extinction is more likely to be a slow process, fuelled by human activity rather than some catastrophic event. The Nature study says the main threats to animal species come from hunting, fishing and other forms exploitation, followed by degradation of habitats. The next biggest, and fast growing, hazard is climate change.

Animals that live at the tree-line of a mountain range are particularly susceptible to climate change. In recent years, scientists have noted northward migrations of animal populations, and plants growing on greater heights than they have been found on mountain slopes.

Highly specialised animals live in narrow geographic ranges near the tree-line, their existence depending on the changing mountain vegetation and the extent of snowfall. As global temperatures rise, taller trees start growing higher on mountain slopes and snows remain on higher peaks, this range shrinks. Some species adapt to this change, but many do not.

The human cost

So what happens if species go extinct? The death of any species of plant or animal has consequences on human well-being. The decline of vultures in India over the last decade is a prime example. Some 97% of the Indian vulture population died out between 1992 and 2007. Farmers had been treating cattle with an anti-inflammatory drug called diclofenac, which incidentally was poison to the scavenging birds. Vultures feeding off rotting animal carcasses would go into renal failure and die.

With a crash in the vulture population, the all-important ecosystem service of scavenging in urban and semi-urban areas fell to feral dogs. As the stray dog population grew, so did the high incidence of dog bites and rabies that led to millions of rupees in health costs. While research has shown that the population of the Indian vulture has risen since 2007 after the government banned diclofenac, it is still a ‘critically endangered’ species according to the IUCN.

Here are some of the animals and birds found in India that are teetering on the edge of oblivion.

Indian Vulture

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Photo: Tarique Sani/Flickr

Gharial

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Photo: Doug Fisher/Flickr

Jeypore ground gecko

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Photo: Ishan Agarwal