The study illustrates a change in the science of palaeobiology: what was once a somewhat speculative field has now become analytical, and different models can be tested against our expectations.

The fish, Dapedium, is known from fossils found in the Lower Lias rocks near Lyme Regis in Dorset, on England’s south coast. It lived side by side with the great sea reptiles of the Jurassic such as the dolphin-shaped ichthyosaurs, long-necked plesiosaurs, and even some marine crocodilians.

Dapedium was one of a number of these animals first discovered by the pioneering 19th century fossil collector Mary Anning, which fascinated early palaeontologists such as Louis Agass and Henry De la Beche, who created some of the first paleoart based on Anning’s fossils.

‘Duria Antiquior’ (1830) by Henry De la Beche – spot the Dapedium. Henry De la Beche

Dapedium was a deep-bodied fish, shaped like a dinner plate in side view, which could grow to more than half a metre in length. It probably escaped being caught by the larger predators pictured above because it was so thin-bodied it might be hard to see head-on. It had a tiny mouth with jutting front teeth and masses of pebble-shaped teeth further back.

Small mouths, big jaws. dinosaurpalaeo / Heinrich Mallison

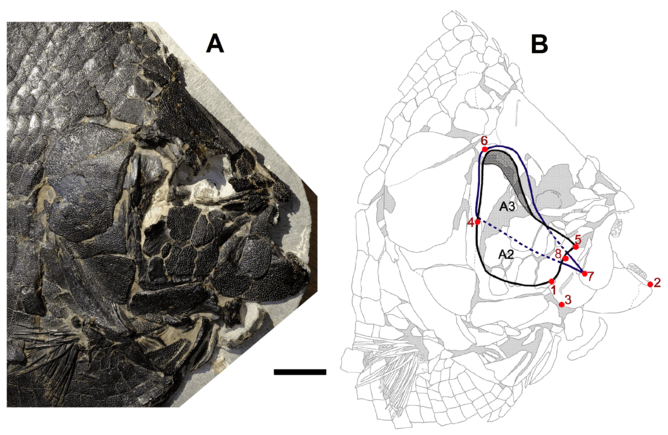

But what were those teeth actually used for? To reconstruct the feeding behaviour of this ancient fish, Smithwick applied a new lever-based mechanical model developed by Mark Westneat at the University of Chicago as a means of quantifying jaw motions and forces in modern teleost fishes. Teleosts have more complex jaws than tetrapods such as ourselves – there is not a single jaw joint, but four, so when it is feeding a teleost can project its mouth forwards in the classic “pout”.

Modelling the exact lengths of the multiple cranks of the jaws, their angles to each other, and likely muscle forces, means scientists have a good idea how all modern fishes use their jaws. Depending on their diet, the jaws operate in different ways to snatch soft prey, crush shells, snip corals, or chew seaweed.

Work in progress. Fiann Smithwick, Author provided

Smithwick applied this model to 89 specimens of Dapedium in the Natural History Museum, Bristol City Museum, and the Philpot Museum in Lyme Regis, and measured the positions and lengths of the jaw bones. He figured out the positions and orientations of jaw muscles and varied these to include all possible models.

His calculations showed Dapedium was a shell crusher. Its jaws moved slowly, but strongly, so it could work on the hard shells of its prey. Other fishes have fast-moving, but weaker jaws, adapted for feeding on speedier fish.

In comparison with modern fishes, Dapedium matches closely the modern sea breams. These fishes are also flat-sided and deep-bodied, and they crush shells in their small mouths, armed with blunt-topped teeth.

Sea bream use their strong jaws to munch through crab shells.

The new research takes what we know about the mechanics of modern fish such as the sea bream and predicts the jaw mechanics of fossil fishes within this framework. Speculation is not necessary.

Smithwick was funded by a Summer Research Bursary from the Palaeontological Association, and he devised the project himself, learned the numerical techniques, and wrote it up himself. It’s rare for an undergraduate to be able to do all this and pass the scrutiny of one of the world’s leading scientific journals.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation.