These fringe characters are often as important than the ones in the lead, in the Marquezian world of Goa’s brass musicians. “The word is 'musician,” I was corrected by one of them as he looked out of the window and tuned his tenor saxophone, “not bandwallah.”

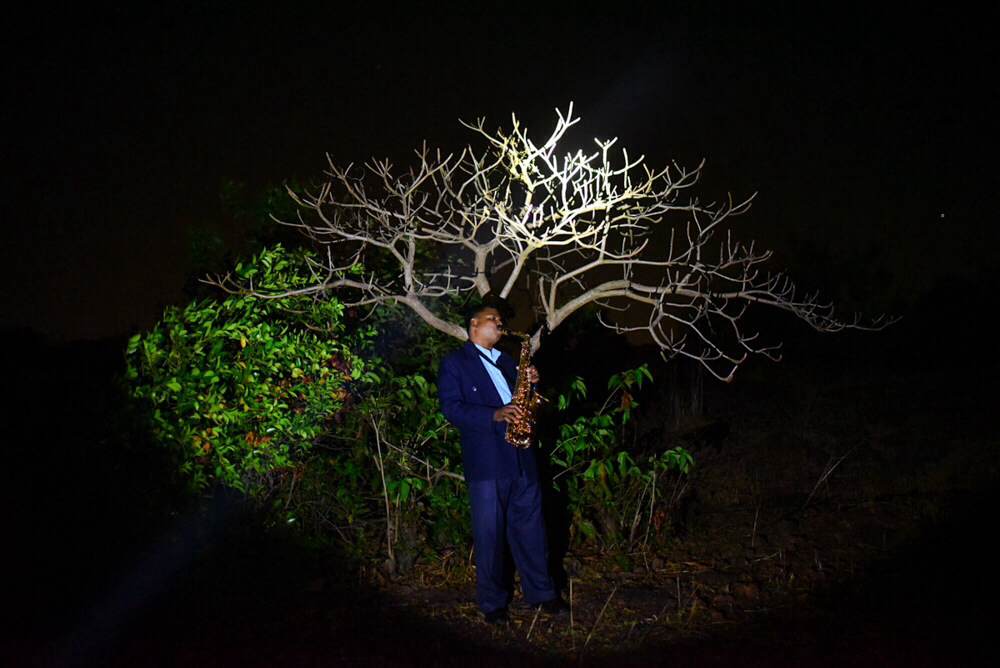

Maybe it’s a matter of semantics. But for the musicians of Goa, who wander from the reverie of a feast to contemplation at a neighbourhood cemetery, their identity testifies to their manner of practice. Music, like a lot of things in laid-back Goa, is intrinsically linked to faith. Their music is not about the theatre that seems to accompany brass performers from elsewhere; it’s a silent call of longing, of remembrances of a time gone by.

It is a dying art, their music of everyday words and songs of love and loss. All of Goa has only one trombone player, and a few scores that play the trumpet and the sax. But like hopeless lovers trying to keep a memory alive, they prefer to look at their world with rose-tinted glasses. As he finishes playing La Vie En Rose, David Pereira introduces me to his cat, called Seventy Five. “You see, her screw is slightly off. She is not a full hundred percent sane. So, you know, Seventy Five.”

Raj Lalwani describes himself as a work in progress, for whom, photography is a little like a cup of Earl Grey – brewed with time.

These images were part of the Bajaatey Raho exhibition in Delhi last year, part of a collaborative project under the aegis of the Neel Dongre Awards/Grants for Excellence in Photography.