But it wasn’t India, and it wasn’t Diwali. It was the first night of Operation Desert Storm in Baghdad – the pre-dawn attack on January 17, 1991. There we were – my parents, my five-year-old sister and myself, 10 years old at the time, stuck in Baghdad as a result of my father’s undying optimism and Saddam Hussein’s hair-raising ambition. Most Indians had already been evacuated from Iraq and Kuwait by the Indian government – one of the largest evacuations in history, in which more than 175,000 Indians were repatriated. It had lasted from August to October 1990, starting right after Iraqi troops and tanks annexed Kuwait.

My father had his own plans. When Kuwait fell, we had been in India on holiday, but as our countrymen were being rushed out of Iraq, my father and a few of his colleagues, all oil refinery engineers, were looking up flights to return to Baghdad. “Pchhah!” he would say. “There will be no war. The era of wars is over.” (Perhaps Saddam Hussein had said that to his kids too.) It would be two more months before we found a flight to take us back to Baghdad and my father to his job. We flew through Amman in Jordan. “Most Indians at the Amman airport were headed in one direction, and we were headed in the other,” said my mother, who was 35 at the time. “Everyone had asked us not to go back. But we just wanted to get back to work.”

We returned to a sporadic, half-lived life. My father would go to work and return in a few hours. Our school was shut. My sister and I were “Chhaaraa goru,” my mother said – stray cows, doing whatever we pleased. It felt like a holiday. From November to January, the markets were flooded with things from Kuwait: face cream, tinned food, clothes, nursery school chairs, even street lights. The only regularity lay in my parents tracking the statements of Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, the United Nations secretary general. The UN had set January 15, 1991, as the deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait.

Two or three days before the deadline, the city started emptying out. Traffic fanned out of the city. People left in buses, horse carts or cars. The markets were open, but there was no one left to shop. “We still thought people were panicking needlessly,” my mother said. “We didn’t really understand the Iraqi news. They would talk about bunkers, but we didn’t get it.” The Indian Embassy in Baghdad had three employees left. Kamal Nayan Bakshi, the ambassador in Iraq, advised the remaining families that borders were still open, and that we should leave before they shut.

The night the planes screamed in from Basra (conducting 400 raids, according to the BBC), my parents finally accepted that it was over. January 17 was the last night we had electricity. Our water, power and telephone lines were cut off. My parents could see the Daura refinery on fire, 20 kilometres southwest of Baghdad.

We stayed on in our little Indian township for another week, washing dishes in the swimming pool. My mother made little diyas with atta, since the shops had run out of candles. Sometimes when the air raid sirens went off, we raced to blow out these diyas in the irrational belief that they could be spotted by the jets. Under parental orders, my sister and I would have to lie flat on the floor, bored to death until the raid ended.

Between the 70 Indians in that township – nearly all Bengalis – we owned one transistor radio. It needed six big batteries, and we could only scrounge together four, but this wasn’t a problem. “It was, after all, a group of engineers,” my mother said. The Indian authorities were no longer able to evacuate us by air, but they did help by giving us 300 kg of rice, sugar, dal, tea, pickle, masalas and salt. My father’s employer, the Ministry of Industry, promised every day that we would be evacuated soon. Ipsita Kumar, one of my closest friends at the time, slept with her packed “evacuation bag” next to her. Her mother, Anjana Kumar, who lives in Kolkata now, recalled to me recently: “We would go to bed with clothes and shoes on. We didn’t know when we might have to make a run for it.”

When we were finally told we’d be evacuated, we put together our two permitted suitcases per family. Our toys, utensils and clothes were abandoned. “We always thought we would go back,” my mother said. “I was so upset at having to leave your toys behind.” We gave our provisions and stores to the Iraqis who ran our township. Our sugar was most welcome. It had already disappeared from the market, and Iraqis like their tea teeth-clatteringly sweet. Just before leaving, my mother put out all the tinned fish we had for our cat Khaboosh, and she asked the Iraqis to keep an eye out for it from time to time.

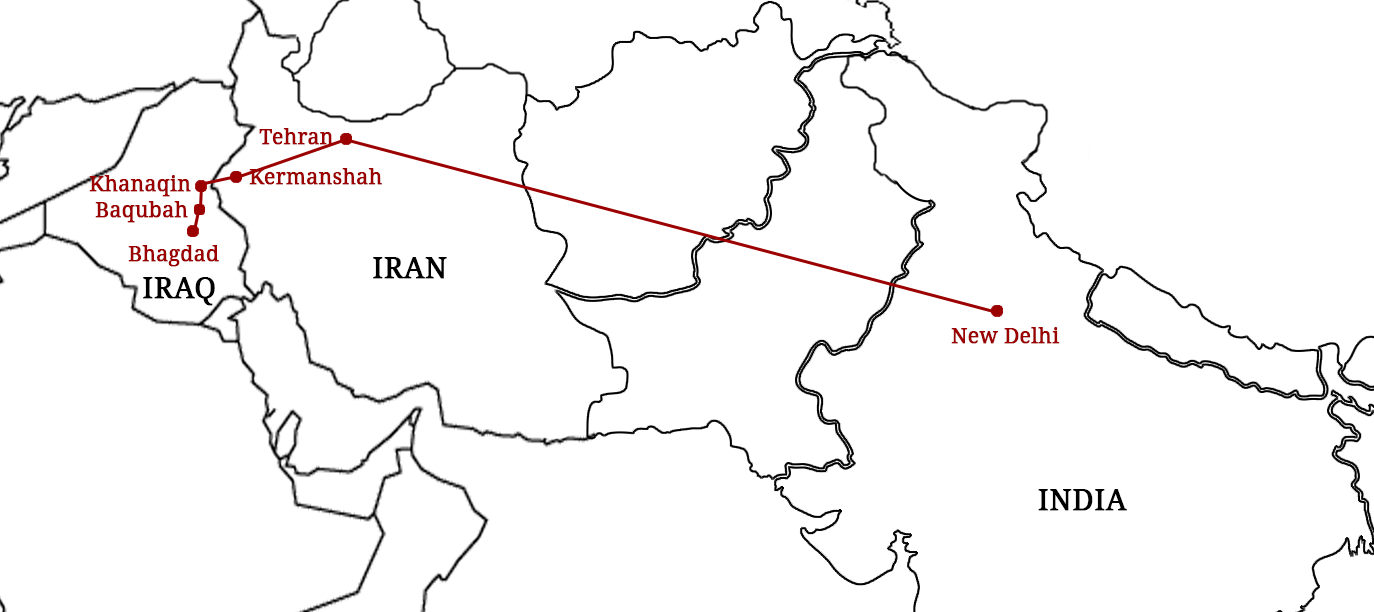

First we went, by bus, to a school building in Baqubah, a town on the outskirts of Baghdad. “On our way there, there was black smoke almost everywhere,” Anjana recalled. “We found out later that it was because they were burning rubber tires to reduce aerial visibility.” In a school building in Baqubah, we were set up in classrooms, each corner of these rooms occupied by a single, huddled family. For the 10 days we spent there, I remember, masoor dal khichri was our staple food, the smell of which even today takes me back to Baqubah. The school had large stores of water, which we shared with desperate Iraqis who came searching for water.

Force 70 Bengalis to subsist on khichri for a week and see what happens. A river ran near the school and it was rumoured that it was well stocked with fish. This turned out to be true and we soon had pieces of fried fish on our plates. Another reason to venture out – in defiance of the Iraqi officials accompanying us – was last-minute shopping. Since our families had been paid our dues from the company, cash wasn’t a problem, so some people tried to buy gold on the way home. My mother wanted jars of Crème 21. En route to the shops to buy bright orange pots of face cream, there was an air raid. The Scud missiles, my mother said, were so close that she could see their sleek pencil shapes.

The missiles missed our school as well as the bridge on the river. That was key. Our main worry was whether we would be able to get out. We didn’t know which country would let us in. The Jordanian border had shut. Would we have to walk to Tehran? Every morning, as soon as they woke up, our families checked to see if the bridge was still standing. That was our escape route.

One day, by bus again, we left for the Khanaqin border, 110 kilometres away. Here, an Iraqi supervisor said: “Ladies, mothers and sisters – please cover your heads from this border.” In this way, amidst driving rain and biting cold, my family traversed No Man’s Land and left Iraq. The Iraqi officials who had guarded us all this way, humouring our indiscipline, handed us over to Iran. “We hated leaving them,” my mother said. “They were the familiar and the comfort. From here on, we would be among strangers.”

After a thorough check of our luggage, the Iranian border officials sealed our audio cassettes, telling us that we couldn’t listen to our music in this unfamiliar new country. They took away our bottles of homeopathy pills. For a night, we stayed in a refugee camp teeming with Indians, Bangladeshis, Sudanese and Algerians. The sounds of bombs were now faded, a comfortable distance away.

In the camp, each family was given a tent pitched on rubble and boulders, cans of food and bread. “They used to carry these large rotis draped over their arms and cut off parts of it to distribute,” Anjana said. Ipsita didn’t eat her share of the bread. Instead, she used it as a pillow, because it was “so nice, big, fluffy and fat”.

The next day, Iranian officials took us to Kermanshah, 500 kilometres from Tehran. Here, after 18 days, we saw electricity and proper beds, and soft, clean, white bedsheets. There was fragrant Iranian biryani to eat. But this was just a night stop. The next morning again, we were back on the bus, headed to Tehran through snowbound terrain. The path was strewn with foxholes and widespread devastation from the eight-year Iran-Iraq war: houses without roofs and ghost towns.

When we reached Tehran around nightfall, we were ushered into an unexpected place: a gurdwara. Here the Indian Embassy in Iran contacted us, asking us to wait for a chartered flight home. The wait lasted 10 days. “But my parents still loved shopping!” Ipsita said, with a laugh. “They went out looking for Persian carpets, watches, cameras and gadgets.” Her father and a few others even went to interview for engineering jobs in Tabriz. It was the walk-in interview to end all walk-in interviews.

I witnessed my life’s first snowfall that year in Tehran. It is the clearest memory I have from my childhood. The more distant the memory, the harder it is to tell truth from fiction or hearsay. A kernel of a memory, often just a single image, is surrounded by layer after layer of received detail, turning into a complete story. It feels inexact, somehow, to even call it a memory – really, it’s closer to a form of collective storytelling.

Tehran was scenic. My mother said it made her feel like she was in Europe. By now, my sister and I had been out of school for eight months, and we had begun to believe that a life without homework was the new normal. But our wild flight ended there. We landed in New Delhi on February 28, 1991. The same day, Kuwait was liberated from the Iraqi occupation.